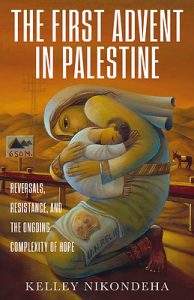

Nerys writes: During the last few weeks, I’ve been reading a book which I’m finding is sustaining me during what has turned out to be a difficult Advent in many ways. I don’t know about you, but for me it’s going to be hard to find much joy in our Christmas festivities this year. It doesn’t feel right to be carrying on as usual when there is such killing of innocent people happening in places like Gaza and in eastern Ukraine, when so many people have been driven from their homes by war and climate disasters and when there is so much economic need in our own communities. What I have learnt from this book, and what gives me hope in the face of the horror and terrible injustice of today, is that it was in a very similar circumstances that Christ was born.

Over the years we have sanitized and prettyfied the Gospels’ account of the first Christmas until it bears little relation to its historical setting in first century Palestine and has little to offer anyone living in troubled times like ours. The book I’ve been reading sets the story in the political and economic landscape of the time – a time of darkness and danger for the Jewish people. For generations they had suffered at the hands of one empire or another and now they were under Roman rule. Caesar had announced the Pax Romana and had been declared the saviour of the world. Through crushing military victory and control maintained through violence, the Romans had ended the cycles of endless wars and brought about world peace. It was at this time that God who is love, came to the hills of Judea and to a village in Galilee to begin a different kind of peace campaign.

God first came to Zechariah, an ordinary priest, and his elderly, childless wife Elizabeth. God then reached towards Galilee to find someone to collaborate with in a plan for a kind of peace that didn’t rely on violence or war or on turning people out of their homes. While the Roman empire would soon collapse, God’s peace would be good news for oppressed people the world over for ever.

But the coming of the Messiah was nothing like any good first-century Jewish man or woman expected. No one anticipated the place or the person that God would approach – least of all Mary, the girl from Galilee.

The people of the north were considered inferior by those in Judea and Jerusalem. Over the centuries they had intermarried with other peoples, they didn’t observe the Jewish Law to the same extent as their southern neighbours and didn’t worship regularly in the temple. These villages were places of resistance to foreign rule – the people always waiting for the next act of aggression in a cycle of protests, uprisings and reprisals. This was the last place anyone expected to be on God’s map.

But it was to Nazareth in Galilee that God sent the angel Gabriel, to the last person you would expect – a local girl from an ordinary family. The Mary of our Christmas cards dressed in blue with her delicate beauty, calm and serene, is not the Mary of Luke’s Gospel. This girl on the verge of becoming a woman would have been shaped by trauma – the collective trauma of her people, humiliated and oppressed for centuries on end, and perhaps personal trauma, existing as she did in a precarious place where sexual violence against women and children was widespread. But a young woman like her, living at a time of great political tension which often spilled into violence, would also have been formed by resistance.

The author of the book I’ve been reading, likens Mary to members of the current generation of Palestinian women in the West Bank who refuse to accept the Israeli occupation. Women like Abed Al Tamimi, from the small village of Nabi Saleh, not unlike Nazareth, who at the age of 16 was arrested for slapping an Israeli soldier. She had grown up marching in community protests against the Israeli settlers who had taken over the village spring and much of their agricultural land. She was only ten when Mustafa, her cousin, was killed by soldiers. The following year, she witnessed the arrest of her mother (which she herself tried to stop) and then the arrest of her older brother. When soldiers came to her front yard just weeks after shooting another of her cousins in the face, she reacted with her fists. The next time the soldiers came, it was to take her to prison.

Before she became and adult, Abed Tamimi had developed a spine of steel. At the age of 22, she continues to resist the occupation, regularly risking her freedom and her life in her community’s quest for justice. Two thousand years earlier, Mary would have seen soldiers riding into Nazareth, terrorizing her neighbours in the name of peacekeeping. She would have witnessed uncles humiliated, cousins hurt and female relatives taken by force to be punished in unspeakable ways. While the men in her community took up arms to protect their lives and land, she might have composed songs of grand reversals and unlikely victories. Formed by trauma and resistance, she would have understood justice as rebellion against the oppression of the empire.

But before she herself could push against it with violence, Mary was pulled into God’s peace-making initiative. The angel insists that she has found favour with God. God’s Spirit would overshadow her body, and she would conceive the Son of God, a rival to Caesar, one who would be able to reshape the world according to justice, bringing a different kind of peace. Mary listens to the promise of the healing of so much hurt and responds with confidence borne of trust. The young rebel is ready to be at God’s service.

In the courtyard of the Church of the Annunciation built on the foundations of what is thought to have been Mary’s home in Nazareth, there is a collection of images from across the world. Most are the classic Madonna and Child motif but each reflects the nation of the artwork’s origin. Together they represent the ways in which Mary and her son continue to be embodied in those precarious places in the world where mothers are practicing non-violent resistance to oppression and teaching their children to hunger for justice and peace

May we in our prayers and actions support those who are continuing what Mary started with her ‘Yes’ to God, and in our own lives may we hold on to the hope which the coming of her son offers us in these dark days.

Kelly Latimore icon: Mother of God: Protectress of the Oppressed