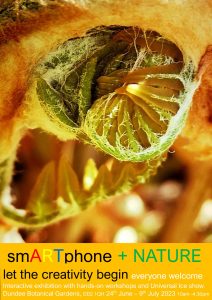

Nerys writes: A few weeks ago, I spent an afternoon at a friend’s art exhibition, learning how to be creative with my mobile phone. She showed me how to zoom in on details in ordinary things in nature and then encouraged me to try using different filters to enhance particular aspects of an image to produce interesting, artistic photos.

Jesus in his parables zooms in on ordinary things – a lump of dough, a treasure trove, a fishing net, a flock of sheep. Sometimes the writers of the Gospels will add a filter which creates a particular effect. Sometimes we the readers do that ourselves when we come to a parable with our questions, our fears, our hopes.

In Matthew 13.24-30, Jesus zooms in on a cornfield infested by weeds. An enemy of the farmer had sabotaged the crop. The servants are keen to take out the weeds immediately but their master prefers to wait until harvest. This situation would have been familiar to many of Jesus’s listeners. Roman law had a punishment for anyone who scattered the seeds of a particular weed in a neighbour’s cornfield. That weed was the bearded darnel, known also as ‘false wheat’. As it grows, its roots surround the roots of good plants sucking up precious nutrients and scarce water. Above ground, it looks just like wheat when young but when fully grown, it produces black seeds which cause hallucinations, blindness and even death if they turn up in the bread dough.

In Matthew 13.36-40, Jesus gives his disciples a detailed explanation of the parable, focussing on the harvesting of the wheat and the fate of the weeds. As the parable appears only in this Gospel, it’s difficult to know to what extent the author has coloured its interpretation with his own preoccupations. Elsewhere, Matthew is very keen on warning his readers about the final judgement when God will divide people into good and bad, faithful and wicked, blessed and cursed. His is the only Gospel that contains the wise and foolish virgins or the division of the sheep from the goats. It is he only who mentions the furnace of fire where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Was he perhaps addressing a growing concern within the church community to which he belonged, a concern shared perhaps by the readers of today’s Epistle? In Romans 8.12-25 Paul also makes a clear distinction between people: those who live according to the flesh who will die and those who are led by God’s Spirit who will live. He provides hope of a release from the Church’s present suffering by using the image of a woman in labour groaning as she gives birth to a new creation. A day will come, he promises, when the kingdom of God which Jesus had brought into the world, will finally be established and all evil and evildoers will be eradicated. In the meantime, the Holy Spirit will give the faithful what they need.

Matthew highlights the harvest but I doubt that this was the idea that would have most interested the crowd on the beach as they listened to Jesus. Most of them would have taken as a given the belief that a time would come when God would judge the world, dividing the faithful from the wicked. Like many Jews of the time, they longed for that day when they would be rescued from oppression and the enemies of their people would be punished. In Jesus they saw God at work bringing in the kingdom. They flocked to him eager to help in the process, probably assuming that it would be in the form of a military rebellion. They would have identified themselves with the slaves of the householder who are keen to immediately root up the weeds in the field. I wonder what their response might have been to the master’s insistence on waiting until harvest time? Would they have seen it as wisdom or folly?

When we look at the parable through the filter of today’s Old Testament readings, Genesis 28.10-19 and Psalm 139, it is the nature of the owner of the field that grabs the attention. Both authors paint similar pictures of what God is like. The psalmist emphasises God’s intense interest in every aspect of his life and God’s care for him. This is exactly what Jacob discovers, as he flees from his brother’s wrath. In his dream he learns that he is not alone. He hears God saying, ‘Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go’, The owner of the field, the one who planted the good seeds, is unwilling to take out the weeds because he doesn’t want to risk a single ear of the crop. He knows that their roots have become entwined with those of the weeds. The only way to avoid damaging the good plants is by waiting patiently until harvest time.

We long for the evils that lead to injustice, corruption and conflict to be uprooted. The parable reminds us how difficult a task this is. The reality is that our world, our communities, our families and sometimes our own lives are like the farmer’s infested field. It is tempting to seek to root out all evil whatever the cost but this isn’t God’s way. We are not called to be the ones who judge others or ourselves. We leave that work for our merciful God to do in God’s time. Rather, we follow the example of Jesus. Just before he tells this parable, the Pharisees try to trick him and begin their plot to destroy him. Jesus knows that they are as false and deadly as any bearded darnel but he is more interested in the growth of the wheat than in weeding out any weeds.

We are called to live with the evil that is among us and within us, patiently cultivating the good. We do this work through the power of the Holy Spirit, knowing that God has promised to be always with us and for us, and in the certain hope that God’s goodness and love will prevail.