Nerys writes: Among my favourite Bible tales when I was a child were those of Zacchaeus and Blind Bartimaeus, two comical and dramatic stories which captured my imagination. But I didn’t realise until this week that these two characters are connected. They form one of the many contrasting pairs in Luke, like the Pharisee and the Tax Collector of last week’s Gospel passage. The chapter divisions of the New Testament have broken the two episodes apart but when we read Luke 18.35-43 and 19.1-11 together, we see that there’s a symmetry to Jesus’ visit to the town of Jericho. As he arrives, he heals the blind beggar and as he leaves, he extends love to the chief tax collector.

In his wonderful book, Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes, Kenneth Bailey draws out the connection and the contrast between the two characters. Both are marginalised and rejected by their community but one is a man oppressed whilst the second is an oppressor.

Throughout Luke’s Gospel, we see Jesus siding with people like the blind beggar. The poor, the widow, the outcast, the refugee, all receive his special attention and compassion. But what about people like Zacchaeus? What about the religious leaders, the soldiers and tax collectors, those who have grown rich and powerful by exploiting others?

It is natural to assume that Luke’s message is that we should simply oppose people like these. After all, in Mary’s Song, the Magnificat, right at the beginning of the Gospel, we are told that God ‘has put down the mighty from their thrones and lifted up the lowly, that he has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty’. Likewise in the Sermon on the Plain, Luke’s Jesus accompanies his blessings of the poor and the hungry with ‘woe to you’ statements, warning those who are living comfortably now that their fortunes will be reversed. And elsewhere, Jesus teaches that is impossible for the rich to enter the kingdom of God just as it would be for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle.

But is it possible to oppose an oppressor and at the same time show compassion towards them? Is there space in the Kingdom of God for a man like Zacchaeus?

Just as with the character of the Pharisee in last week’s parable, there is, I think, deliberate ambiguity and also a certain irony in the way Zacchaeus is presented by Luke. Most of us are so used to reading the story in a certain way that we only see the individual and his conversion. But Zacchaeus was part of a community whose response to him and to the blind beggar shows that they are as far from God’s kingdom as they thought he was.

The good people of Jericho would have despised Zacchaeus. His name is a diminutive form of Zechariah, derived from a Hebrew word meaning ‘pure’, but in their eyes there was nothing pure about the way of life he had chosen. Zacchaeus was rich in the worst possible way. He had become wealthy by exploiting his own people and collaborating with their enemies. You couldn’t blame his victims for shutting him out of their lives or even for taking the opportunity on that fateful day to get their own back on him by blocking his access to Jesus.

Zacchaeus may well have been physically small but he would also have been regarded by his community as being small-minded – petty, greedy, with a low expectation of himself. Here was someone who hadn’t ‘grown before God and people’, someone who had sold himself short, who certainly wasn’t living up to his name. And yet, paradoxically, Zacchaeus had retained a childlike ability to keep seeking the truth. He really wanted to see who Jesus was. And like a child, he scampers up a tree to get a better look. In his eagerness to respond to God’s call, he forgets decorum and even neglects his own safety, putting himself in an extremely vulnerable position.

Having found him in that tree, the crowd look to Jesus to express their anger and hatred towards their oppressor. Instead, Jesus does the unthinkable. He invites himself for a meal in Zacchaeus’ house. In doing this, he neither endorses the oppression nor ostracises the oppressor. Instead, he expresses God’s love and acceptance of the individual and by accepting this love and responding to it, Zacchaeus discovers repentance and restoration.

The love expressed by Jesus to Zacchaeus is a costly love. It shifts the crowd’s hostility against Zacchaeus to himself. The community is able to accept the criticism that is inherent in Jesus’ healing of the blind man, someone they themselves had oppressed and rejected, They respond by joining him in his praises to God. But seeing Jesus offering the same special grace to their oppressor is a different matter. The mood of the crowd changes again; praise turns to the muttered condemnation which had already become so familiar to Jesus and which would dog his footsteps as he continued on his final journey to Jerusalem.

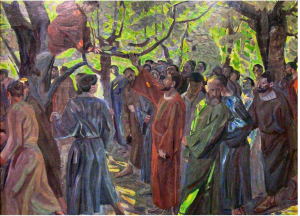

In today’s increasingly divided society. it’s often easier and safer to vilify the other rather than to try to understand and offer love. Before you pray for both the oppressor and the oppressed in our world, our community and our church, I invite you to explore the painting below made in 1913 by Danish artist Niels Larsen Stevns, I wonder where you would place yourself in the picture and why?