Nerys writes: I’m sure you’ve noticed that the word ‘amazing’ has changed its meaning in recent years and largely lost its power in everyday speech. Advertisements talk of ‘amazing prices’, ‘amazing quality’, ‘amazing colours’. Young people will say that they have been to ‘an amazing concert’, and heard ‘an amazing singer’. None of this has the sense of astonishment or bewilderment that is so often associated in the Gospels with Jesus. It is not surprising that his actions caused amazement, but his words also gave rise to a similar reaction. The multitude who heard the Sermon on the Mount, the crowds in the synagogue at Capernaum and in his home town of Nazareth, even his own parents overhearing him as a young boy in the temple – all were amazed at what he said and we find the same reaction in today’s Gospel reading, Matthew 22.15-22.

The Pharisees were confident that they had discovered a way get rid of this young man who was becoming such a thorn in their sides. They must have burnt a lot of midnight oil planning this trap. They had even joined with the followers of Herod – a group they bitterly opposed – to come up with a perfectly formulated question which would cause him to discredit himself by his own words before the large crowds of worshippers in the temple courts. Whichever way he answers their question, he is sure to alienate some of the crowd and find himself in big trouble. They think they’ve got him. They flatter him, trying to lull him into a false sense of security, before launching their attack.

Yet, within a few seconds, they are the ones scrabbling red-faced for answers to his questions, with their clever strategy completely destroyed. They are amazed – and shamed – by what they have heard from his lips and have no option but to scurry away with their tails between their legs.

What was it that Jesus had said this time that caused such amazement even among his enemies? Was he just clever with words, or did he speak some divine wisdom and truth that we also need to hear?

On the surface, the Pharisees’ question was to do with money. Is it right to pay taxes to Caesar or not? But there was much more to it than that. It wasn’t just that the people of Israel didn’t like paying taxes, or that this tax represented for them the oppression of foreign occupation. Devout Jews believed that using the Roman coin, the denarius, to pay the tax was idolatry, an offense against God.

This is why, before saying anything else, Jesus asks the Pharisees to bring him the coin in question, stamped with an image of the emperor’s head and inscribed around the edge with words that would send a shudder through any believer – Caesar, Son of God. This request is, in fact, the beginning of his answer because when these religious leaders produce the coin, they are admitting their hypocrisy, showing everyone that they themselves were handling the hated currency. ‘Whose is this image?’ Jesus asks. ‘And who is it who gives himself an inscription like that?’ He doesn’t say anything that could get him into trouble but the questions he throws back at them show very clearly what he thinks of Caesar’s presumption and of their complicity.

Well then, he continues, ‘you’d better pay Caesar back in his own coin’. What did he mean? Was he inciting a revolution or was he, as he stood there with the coin in his hand, simply saying that the tax should be paid? The deliberate ambiguity of these words is so clever.

The Tribute Money by Rubens

But then, almost as an afterthought, he adds ‘and you’d better pay God back in his own coin too.’ Amazement! With these words a new and completely different dimension is added to the question and the dilemma is resolved. The Pharisees are now looking like fools. They are meant to be experts in religion but they never thought to introduce God into the debate. If we give back to Caesar what is his, we need also to give back to God what is God’s – and every Jewish child would know what that meant. It was clear from the words they recited every morning and evening: Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, is the only LORD. You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. The first duty of every Jew is to offer to God the worship, love and service of their whole lives as our psalm today, Psalm 99, makes clear. Caesar’s claims are as nothing before the all-embracing claim of the one true God.

Everyone is amazed. Once again, it appears that this young man knows more about their heavenly Father than all the religious leaders put together. And he has spoken with an authority which surely could only come from God himself. As the Pharisees leave with their anger and hatred undiminished, it doesn’t occur to them that Jesus’s response might be a last appeal by their God who loves them, for them to change their ways and turn back to him. They hadn’t wanted a real answer to their question, so they didn’t hear it in this way. But, if we look at the wider context, Matthew allows us to see the situation in a different light. He has carefully placed this episode after a series of parables about people who refuse to give God his due, who will not recognise his Son and rejoice with him.

So here we have the true Son of God, standing before us just days before he will give himself up to death. He isn’t interested in wriggling out of personal danger. He isn’t interested in leading a tax revolt. Jesus is on his way to embody God who is love, whose face was hidden from Moses but which will be unveiled at last and made known personally to all his children. He is on his way to defeat for ever through his self-giving love, the power of all the Caesars of this world by defeating once and for all the power of evil and death.

The risen Christ is standing before us this morning, asking us to consider afresh how we should respond to God, source of everything we enjoy including life itself. Will we turn away like the Pharisees or will we, like the young Christians addressed by Paul in today’s epistle, 1 Thessalonians 1.1-10, repay God by becoming imitators, sharing God’s love and goodness with everyone we meet? The choice is ours.

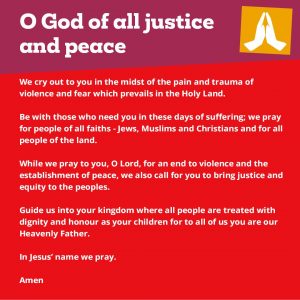

This week we are called to pray in particular for a just and sustainable peace in Israel and Palestine. You may wish to use this prayer issued by Christian Aid.

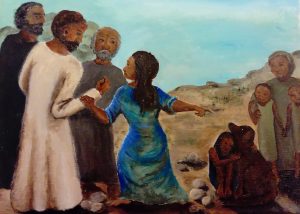

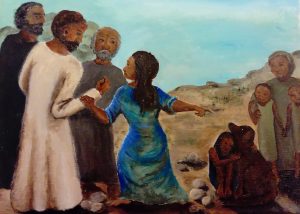

Moira writes: As you prepare for worship, today’s readings are Exodus 32,1-14, Philippians 4.1-9 and Matthew 22.1-14. The image is from the Jesus Mafa collection, depicting the parable of the Wedding Banquet.

In this morning’s Gospel we hear a very strange parable about guests invited to a wedding who reject the invitation and behave very badly. As in all good stories, the strong point, the most telling point, comes at the end – the condemnation of the man who accepted the invitation to the banquet but came without respect for his host. But how could someone, who was called in from the street, possibly come prepared with a special robe? I suppose when we think about it, it’s no more surprising than the equity of paying the workers in the vineyard, in the Gospel passage two weeks ago, the same rate for unequal hours worked! Perhaps we are taking this passage too literally. The guest at the banquet looks like he was being a bit too casual, not just in the clothes that he wore, but maybe he was thinking more about the food. In our first reading this morning, we see that those who have been called by God to be his chosen people are once again rebelling and showing no respect for him. They are being led to freedom, to a new land, but they are not satisfied with what God has provided for them and this gives them an excuse to turn away and worship the golden calf.

In the time of Jesus, it was common to invite guests to the elaborate wedding festivities well in advance of the day. And then a reminder invitation would go out just before the feast. To have been invited not once but twice and then not to have attended would have already amounted to a great slight to the host. But in this parable, this is not the worst thing that happened! The guests not only refused to show up, they abused and even killed the king’s messengers that came to remind them about the invitation. The following words in this passage are very hard to hear. The king was so enraged he sent out his troops to destroy the murderous guests and burned their city, and then he sent the troops out into the streets to invite anyone there to come to the banquet. When the king then noticed the man not wearing a wedding robe his following words are somewhat harsh, after all, the man did accept the invitation. The king’s words once again seem so unfair. “Bind him hand and foot, and throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.” For many are called, but few are chosen.’ Not exactly encouraging words!

Thank goodness that Paul had such encouraging words in our Epistle. Paul addresses his Philippian community as his brothers and sisters and encourages them to stand firm in the Lord, telling them how they can do this. They are to ‘support and help one another at all times.’ Most importantly, they are to ‘rejoice in the Lord always, showing gentleness to everyone and taking their worries to God in prayer and supplication with thanksgiving’. If they can do this, then ‘the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding will guard their hearts and minds in Christ Jesus.’ Those of us who know and love God, should find that it makes a difference in our lives. Life is, I believe, to be lived in joy and hope, with love towards others, thankful for the blessings we have received, obedient to the call of today and with confidence in the future when God’s whole purpose is complete.

After those comforting and encouraging words from Paul, I’m afraid we must return to our Gospel parable of the Wedding Banquet. How easy it is for us, with our busy lives, to regard or disregard an unexpected invitation as an intrusion. In an age of consumerism, we hear more about rights than privileges. We control our choices. Whether to support and do something about climate change as we have discussed in the Season of Creation. We can choose to buy locally or continue shopping in large supermarkets, we can choose to buy only vegetables and fruit when they are in season, or whenever we want to eat them regardless of where they have been grown. The choices are ours to make. We surf the internet for news, but we decided what we want to see or read from its many options. No one has a claim on us unless it’s our choice. When God says, “Seek ye first,” we respond with “let me first…” We often put our needs first before responding to God’s call. Those who were invited to the banquet that day, made light of the call. One went to his farm and one to his business. There is no sign of either of these men engaging in unsavoury activities, and yet the King was enraged. It makes us think, why was the king so harsh in his words and actions? However, we must not miss the point – these were responsible busy people in the everyday working world. They were simply so consumed with the “dailyness” of their tight schedules, that nothing could break through – in their eyes, even God could wait! The invited guests who turned away and refused the King’s invitation may well have been doing good things on the farm and at business, but in their busyness, they missed out on the banquet. If a person is full (or busy) an invitation to a feast is not good news. No wonder Jesus said in his Sermon on the Mount, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.” Those whose stomachs and schedules are full, cannot experience a spiritual hunger for the kingdom of God.

There is a postscript in our parable this morning that makes us ask questions, something that Jesus often does in his parables. The King arrives at the banquet, greets his guests, and notices that one of them is not wearing a wedding garment. When asked why, the man is speechless, and so the host has him forcefully evicted and thrown into the darkness. We are never told why the man didn’t observe the dress code. Was he a latecomer and all the robes were taken? Did he not have time to change his clothes? Why would a king who was gracious enough to invite the man in the first place, turn around and rudely evict him from the banquet? One commentator suggests that garments may have been provided at the door and this makes the man’s refusal to wear one more serious. Even then, the punishment seems cruel and unusual for the crime. It wasn’t as if Jesus was particular when it came to clothing. Again, in the Sermon on the Mount, he said, “therefore, I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you shall eat or what you shall drink, nor about your body , what you shall put on.” This dramatic turn in the parable has little to do with dress code I think. Some of the guests had made light of the invitation by staying away, but this man was making light of the invitation after he had come along.

God’s gracious invitation always comes to us, as we are, but we need to come to him not as we were. God’s grace is free, but it is not to be taken lightly. We must not assume that once we are at the Lord’s table we can stay as we are. As consumers of God’s grace, we dare not be presumers of that grace. In other words, we mustn’t take it for granted. As Christian’s we must not regard belonging to our church community as a right rather than a privilege. We must try to see the call to God’s banquet as something we receive with joy and gratitude. As Paul says, we must ‘rejoice in the Lord always,” and try to feel the urgency of God’s call to come to him, to his banquet, to his table with thanksgiving in our hearts. “For many are called, but few are chosen.”

You may wish to pray this prayer by Raymond Chapman

Gracious God, I am often an unworthy guest at your table. I come to you carrying my doubt and anxiety, my resentment of other guests, my indifference to seeking your full purpose for me. Have mercy on my weakness and bring me to a right mind and a true heart in your service, so that I may not fall under judgement when I taste your feast. Amen.

Nerys writes: During the last four weeks we’ve been finding out what we could do to help stop Climate Change and to support the people who are worst affected by the climate crisis. Today, as we give thanks to God for this year’s harvest and for all the good things we enjoy, our readings encourage us to consider how we are going to respond to what we have learnt.

We start with another instalment from the story of Moses and the people of Israel, Exodus 17.1-7. The people had been led by God out of slavery in Egypt. They had been guided by a pillar of smoke by day and fire by night. God had parted the Red Sea so that they could escape and drowned their enemies. In the wilderness when they were hungry, God provided amazing food for them. When the water was too bitter to drink, God provided sweet water. In today’s episode, they are again thirsty and God provides water out of a rock. You would have thought the people would be thankful. But, oh no, whenever things don’t go their way, they complain and grumble and threaten poor Moses. ‘Why did you bring us out of Egypt if we’re to die here? God is obviously not with us, otherwise we wouldn’t be suffering like this.’ Not once do they praise God. Not once do they give thanks.

When things go wrong for us, it’s natural to look for someone to blame, rather than take responsibility for the situation. It’s easy to catastrophise rather than count our blessings. Time and time again, God had shown the people of Israel that he was with them, that he would provide for them. Time and time again, the people lose their trust in God. Instead of following Moses’ example, listening for God’s voice and following God’s instructions, they spend their time grumbling and complaining.

In today’s Gospel, Matthew 21.23-32, the chief priests and elders weren’t listening for God’s voice or following God’s instructions either. They were too busy trying to catch Jesus out with their trick questions. But Jesus ties them up in knots with their own words and they end up looking very foolish. Then he tells them the story of the two brothers who are asked by their father to work in his vineyard. The parable ends with a question, ‘Which one of the two did what his father wanted?’

I wonder how you would have answered Jesus’ question? Was it the one who said no at first but then changed his mind? Or was it the one who seemed very willing but who didn’t follow his polite words with action?

‘It was the first son, of course,’ said the chief priests and the elders, thinking they were very clever. ‘Well, ’ said Jesus, pointing to some people at the edge of the crowd, ‘if that is so, these tax collectors and other outsiders will be in God’s kingdom before you’. Those people had made wrong choices. They had refused to listen to God and follow God’s instructions, but, unlike the religious leaders, when Jesus came among them, they set about making changes to their lives.

God is calling us to make changes to our lives out of love for our planet and for people who are suffering because of climate chaos. How will we respond? Will we show willing, using the right words but not actually do anything or will we put our trust in God into action?

May we be inspired by the prayer below composed by Rt. Revd. Sally Foster-Fulton for this year’s Season of Creation.

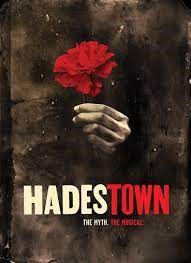

Rachael writes: I heard a story for the first time this week: the ancient Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, although I have learned it as it is retold in the Broadway musical “Hadestown”.  Orpheus is a young singer-songwriter, madly in love with Eurydice. They’re a penniless couple and as winter arrives, Orpheus’ fixation on his song writing leaves Eurydice hungry, tired, and desperate. She is found by Hades, the King of darkness and shadow, the King of the underworld, who convinces her to enter the underworld with him where she signs her life over to him. Immediately she begins to lose herself among the indentured masses of Hadestown. Orpheus of course realises what has happened and takes a very long road to the underworld. He finds her there, but Hades is reluctant to let her go eventually agreeing that they may leave on one condition: as they go along the dark, winding road, over the wall and back to the surface, Orpheus must walk in front while Eurydice walks behind him. And Orpheus must never look over his shoulder to check if she is there, or else she’ll return to Hadestown forever. In the musical Orpheus asks his mentor Hermes whether it is a trick. Hermes replies, ‘No, it’s a test’. They begin the long journey but over the singing of the masses of the underworld Orpheus cannot hear footsteps nor Eurydice’s voice. He has no idea whether she’s there. They persevere until just as Eurydice sings that she can see the light and this is almost all over, Orpheus loses his nerve and turns round. He sees Eurydice there with him and he knows that he has condemned her to an eternity in Hadestown. Orpheus is a young singer-songwriter, madly in love with Eurydice. They’re a penniless couple and as winter arrives, Orpheus’ fixation on his song writing leaves Eurydice hungry, tired, and desperate. She is found by Hades, the King of darkness and shadow, the King of the underworld, who convinces her to enter the underworld with him where she signs her life over to him. Immediately she begins to lose herself among the indentured masses of Hadestown. Orpheus of course realises what has happened and takes a very long road to the underworld. He finds her there, but Hades is reluctant to let her go eventually agreeing that they may leave on one condition: as they go along the dark, winding road, over the wall and back to the surface, Orpheus must walk in front while Eurydice walks behind him. And Orpheus must never look over his shoulder to check if she is there, or else she’ll return to Hadestown forever. In the musical Orpheus asks his mentor Hermes whether it is a trick. Hermes replies, ‘No, it’s a test’. They begin the long journey but over the singing of the masses of the underworld Orpheus cannot hear footsteps nor Eurydice’s voice. He has no idea whether she’s there. They persevere until just as Eurydice sings that she can see the light and this is almost all over, Orpheus loses his nerve and turns round. He sees Eurydice there with him and he knows that he has condemned her to an eternity in Hadestown.

Orpheus tried but couldn’t help himself. He had to look back. Just like in our Gospel reading (Matthew 20.1-16) where the labourers who, when handed their wages, have to look at the other guys and say, “Hang on a minute”, rather than simply looking in their hand and being grateful, or even thinking of the possibilities ahead of them. And just like the Israelites on their desert journey (Exodus 16.2-15) who could not focus on the freedom of the moment or on the promise of God for the future, but had to look back and down the bitter road.

Both passages give us a vision for a future which we can be so reticent to look to – the equitable distribution of bread and meat throughout the wilderness congregation, and the extravagant equity for all on the landowners payroll. I wonder if we too will exclaim “This isn’t fair!”? Perhaps in the same way that we do in conversations around benefits, bonuses, and citizen’s wages? Because ideas of fairness, of “just deserts”, are the Hadestown that we are trying to walk out of but can’t help ourselves in looking back to.

There is no commandment to be fair, nor is it a spiritual discipline or a fruit of the spirit. It’s a human construct that attempts to masquerade as justice. Fairness pretends to treat everyone the same, where justice makes everyone whole. Fairness pretends that everyone is equal, while hospitality acknowledges that we are mutually dependent on one another. Fairness pretends we have equal access to the resources that meet our needs, while generosity proclaims that we never lose when we share our abundance. These tales of abundance make it clear that fairness lies behind and that God promises something much richer ahead.

The parable of the labourers sits between two bookends: in Matthew 19:30 Jesus introduces it by saying, “But many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.” Then he concludes by saying it again in Matthew 20:16—“So the last will be first, and the first will be last.” Jesus is saying God’s abundant grace threatens to upset the predictable seating arrangement: to turn the world upside down and inside out— or rather, turn it right side up and outside in.

It means that those of us used to the privilege of wealth and choice, must restrain our consumption. We must advocate and campaign with those who are don’t normally get a seat at the table, even giving them ours. We use our votes and our voices to implore rich nations like our own to pay for the loss and damage inflicted by climate change in the global south. We lobby our MPs to hold our backwards looking government to account, insisting that they re-impliment plans to scrap new petrol cars and gas boilers, and to enforce energy efficiency regulations in the rental sector, so that we achieve net zero by 2050. We keep our eyes fixed on Christ who leads us to an abundant, grace-filled future.

God isn’t out to test us like Hades and doesn’t hide behind us but actually gives us a very real foretaste such a future in the Eucharist. We all come in the same way and receive the same thing. No matter our status or the state of our bank account. Here, we get everything we do not deserve and it is intentionally “unfair”. Here, we are the labourers and the desert dwellers invited to Christ’s feast of radical hospitality and grace.

In a hopeful moment near the beginning of the musical, Orpheus offers a toast to Persephone – the goddess of spring growth. And I leave you with his words:

“Persephone who has finally returned to us with wine enough to share

Asking nothing in return except that we should live

And learn to live as brothers in this life

And to trust she will provide

And if no one takes too much

There will always be enough

She will always fill our cups

And we will always raise them up

To the world we dream about

And the one we live in now”

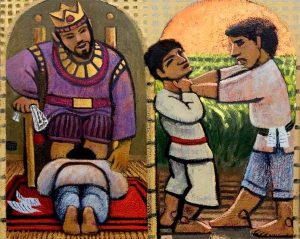

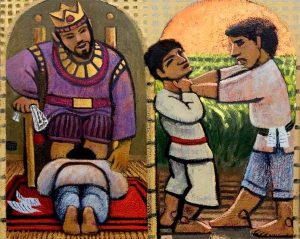

Nerys writes: Today’s Gospel, Matthew 18.21-35, contains a story about debts that can’t be paid and the need to let them go. A wealthy slave had found himself in an impossible situation. In the Roman world, slaves were known to speculate with their masters’ resources in order to accumulate money to buy their freedom. Things had gone badly wrong for this one. He had run up an astronomical debt which he could never repay. The king orders the slave’s possessions to be sold along with the slave himself, his wife and his children. In desperation, the man falls to his knees and promises to pay back everything he owes if his master would just be patient. It is an absurd promise but the king, moved by his plight, has pity on him and releases him of his debt, giving him back his life out of the goodness of his heart. Within moments, the slave has an opportunity to repay the favour by releasing a poorer colleague from a much smaller debt. Instead, he grabs him by the throat, demanding his due and, when the man asks him to be patient just as he had asked the king, he has him thrown into jail.

Artist: Wayne Forte Artist: Wayne Forte

There is no doubt that Climate Change-related disasters are throwing people into debt across the world but it is much worse in some countries than others. On an individual level, a family in rural Malawi or Bangladesh struck by floods or drought, will lose the annual harvest they depend upon for sustenance and income. The only way to buy necessities and seeds for the following year is to borrow money. Survival becomes more and more difficult as the family struggles to service the loan and when the next disaster strikes, they lose everything. The same is happening on a national level. Mozambique, for example, was devastated in 2019 by Hurricane Idai, one of the worst tropical cyclones to affect Africa on record. The government was forced to take out loans from wealthy countries to build new roads, hospitals and schools. Then, last year, another cyclone destroyed some of the infrastructure that had been rebuilt. And in March this year, flooding caused by Hurricane Freddy wiped out the harvest in many areas and impacted the livelihoods of thousands of fishermen and farmers. Each disaster has increased the debt which the government of Mozambique needs to repay, driving the country deeper into extreme poverty.

Least developed countries like Mozambique, Malawi and Bangladesh are urgently calling on the governments of wealthy industrialised countries like Scotland to recognise the impact on their economies of extreme weather events caused by climate change and to take responsibility for it. They argue that it is only right that the countries and the companies which have contributed most to increasing greenhouse gas emissions should pay for the loss and damage they have been causing through many decades of pollution. At COP 27, last year’s United Nations Climate Conference, governments agreed to create an international fund to support lower-income counties hit hardest by the climate crisis. Scotland became the first industrialised nation to commit funding to support the recovery of communities affected most, pledging an initial £2 million at COP26 in Glasgow, rising to £7 million last year. But that is just a drop in the ocean and many other countries and the large fossil fuel companies who are literally fuelling the crisis, are reluctant to contribute a penny. Right now, the fund is not yet in use as those who could easily provide the aid that is needed seek to find ways to avoid bearing the cost.

The whole narrative of the Plagues and the Exodus in the Old Testament readings this month illustrates the connection between environmental disruption and human injustice in a brutal and horrifying way. Had Pharaoh allowed the enslaved Israelites to be set free, his people wouldn’t have suffered such losses. Time and time again Pharaoh refused to listen to the voice of God calling for a just society. In the end he reaped the consequences of his intransigence.

Our God is a God of justice, but also, as Psalm 103 reminds us, a God of compassion and love, slow to anger and rich in mercy. All these qualities are seen in the king of Jesus’ parable who seeks to govern his people by example. When he set his slave free of the burden of impossible debt, his concern was not only for that individual but for his whole kingdom. His intention was for that man to experience forgiveness so that he would in turn forgive others. He was setting an example of costly, sacrificial giving in order to change the attitudes of a whole society of people towards one another.

The parable is presented in Matthew as a response to a question by Peter, voicing the thoughts of the disciples about forgiveness. ‘Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?’ Peter would have considered himself to be extremely generous to be suggesting forgiveness that stretches to the seventh offence but, as ever, Jesus shocks both him and us. Suddenly we get a glimpse of God’s kingdom where forgiving others, releasing them from impossible debt, is a way of life.

Inspired by this vision, we need to lead the way by our example, living and working to create a more just and compassionate world where individuals and countries are set free from the burden of debt caused by Climate Change. While it is important for us to seek to minimise our personal impact on the environment, this is not enough. We need to pray and to raise our voices on behalf of those least responsible for the climate crisis who are being hit hardest and are left paying for the damage. As we stated at Alexander’s baptism a few weeks ago, our task is to live and work for the kingdom of God.

You may wish to use this prayer of thanksgiving by Val Brown, Head of Christian Aid Scotland, as you bring your response to God.

God of all people, of all creatures;

Thank you for the world that you have created,

where each ecosystem lives in delicate balance

and where the world produces the food

and the clean water that we all need to sustain life.

The bounty of the harvest is a testament to the wonder of creation

and yet we know that all creation is groaning.

The weather isn’t what it was

and that throws out the created balance,

making it harder for farmers to grow the food we all need.

Thank you for the efforts of people locally, nationally and globally to care for your world:

for the people who use their creative energy to work for solutions,

for the people who raise their voices to call for justice,

for the people who make small changes every day

to tread more lightly on the earth.

May we all learn to live simply, so that others can simply live. Amen

Christian Aid Libya Floods Appeal

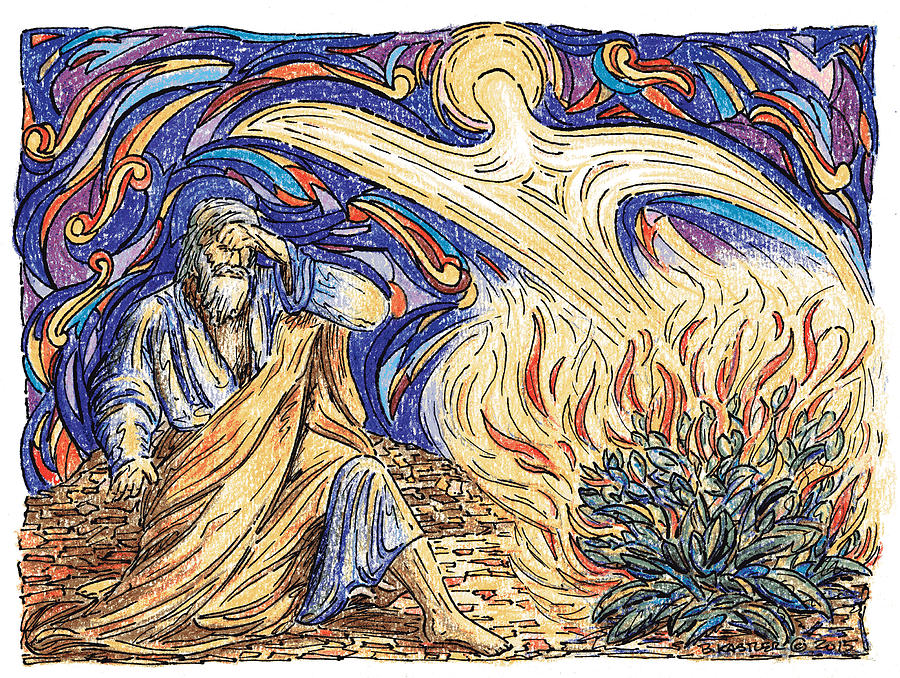

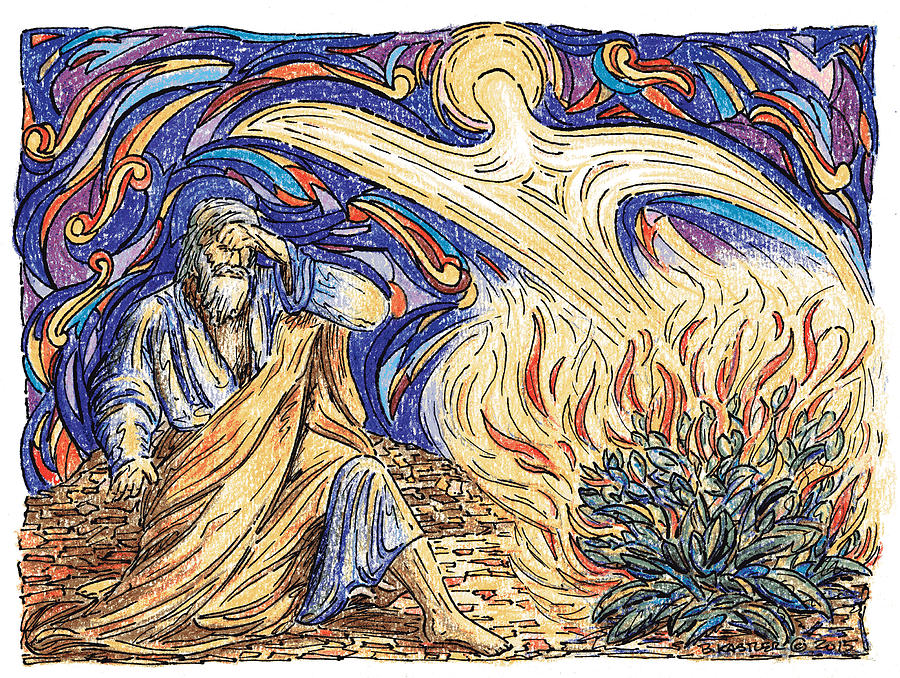

Rachael writes: At the burning bush, Moses is called to make a change (Exodus 3.1-15). He’s essentially been in hiding in Midian, enjoying the quiet and humble life of a shepherd and raising his family in relative safety. He knows the plight of his fellow Israelites but he has left them behind. Perhaps it seemed too big a battle for one person, especially one whose self-confidence is non-existent and who describes themselves as “slow of speech and slow of tongue”.

It’s the perfect story to start the season of creation with: the burning bush (forest, home, town) is an image that we are sadly now all too familiar with. In Hawaii, Canada, Greece, Kazakhstan, Chile, even here in Scotland. Millions of hectares, hundreds of lives. Each one is a reminder for those of us living in relative safety of the plight of the planet. The battle can seem too big for any one of us, even a small group of us, especially when we doubt the power of our own actions and voices, when we think of ourselves as slow of speech or tongue. But we too are being called to make a change.

God says to Moses, “I have observed the misery [and] heard their cry on account of their taskmasters”. “Who am I that I should go?” Moses replies. “I will be with you” God assures him.

What precisely does that call look like for us in 21st century Scotland, facing the issue of global environmental catastrophe, rather than one man 1000 – 1500 years before Christ going head to head with the ego of a despot?

It’s not a new call. Actually, we really need to rediscover the calling given us at our creation, as part of creation: our calling to serve. Humanity was ordained not to be masters or even custodians (that’s God’s job) but to be the servants of creation. To till and keep the earth. Not abuse or destroy it for our own gain. Somewhere (that we might call The Fall) we lost sight of that. Where we should have been servants, we thought ourselves masters. Where we should have grown a garden, we made ourselves gods.

The Office for National Statistics figures show that the median annual income for a man in 1973 was just short of £2000. The average price of a house in June that year was a little over £8000. Today the average annual salary is about £20,000 and the most recent figure for the average house price in the UK is £286,000. And our expectations of those very expensive houses are very different to 1973. Not just a fridge freezer but a spare freezer in the garage for a rainy day. A TV, not just one but one in almost every room, with not just 3 channels but 100s plus every streaming service going. Central heating in every room. At least one car, probably two, on the driveway. And many of us expect to leave that home on holiday for a week or so, multiple times a year, and on at least one occasion to go abroad. We add smart devices, robot lawnmowers, and self-cleaning toilets. We have guest rooms that we pray no one asks to use because we have a permanent guest called Clutter and their friend, Extra Storage.

Desmond Tutu once wrote “The taste of “success” in our world gone mad is measured in dollars and francs and rupees and yen. Our desire to consume any and everything of perceivable value – to extract every precious stone, every ounce of metal, every drop of oil, every tuna in the ocean, every rhinoceros in the bush – knows no bounds. We live in a world dominated by greed. We have allowed the interests of capital to outweigh the interests of human beings and our Earth.”

The only counter to such greed, to such consumption, the only thing that can save the planet now, is restraint. This is the new cost of living: to deny ourselves. For what will it profit us to gain the whole world, but forfeit our life?

Jesus tells us to set our minds on divine things, not human (Matthew 16.21-28). And if we set our minds on the Divine Christ, we see again that same call. For Christ came not to be served but to serve, to lay down his life for his friends, to make himself nothing and take on the nature of a servant.

There are two things I think that looks like at this time. The first is to realign our thinking so that human flourishing looks like compassion and altruism and community, not growth of numbers, productivity, or money. The second is to truly inhabit such thinking and find a way to give away what we have. To tithe, to share. To live out of abundance and generosity. John Bell, of the Iona Community, said at Greenbelt that for years he has had a note stuck to his front door which he sees every time he leaves the house and that it says “Give something away today”. And he has, every day. And he’s never missed a single thing.

Life is not found in what we possess. The more we buy, the more we are bought. But life is found in what we give. What will we give in return for our lives and the life of the planet?

We pray:

God Most High, maker of heaven and earth, you created humankind in your own image and entrusted the whole world to human care: give us grace to serve you faithfully, that we might be trustworthy stewards of your creation, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Nerys writes: Today’s Gospel passage, Matthew 16.13-20, is a conversation between Jesus and his disciples which contains two questions and three answers.

Jesus takes his disciples a long way to the north, to Caesarea Philippi, a town named after the Roman Emperor Caesar and Philip, son of Herod, a Roman puppet king. It is in this place that Jesus invites them to name him. The first question he poses is easy for them to answer. Other people have placed Jesus among the prophets who over the centuries had spoken out against foreign rule and prepared the people of Israel for the coming of God’s promised one. The second question is more challenging but Simon Peter responds. Whether he blurts out what he personally thinks or speaks on behalf of the others, his answer would have been mind-blowing to anyone listening in. To recognise that Jesus is that promised one, the Christ, is to proclaim a new world order. Jesus commends Simon for this insight which has been given to him directly from God.

This isn’t the end of the conversation. Simon doesn’t ask his own question out loud but Jesus knows what is in his heart and in the hearts of his companions: ‘But what about me? If you are the Christ, the Son of the Living God, then who am I in relation to others and in relation you?’

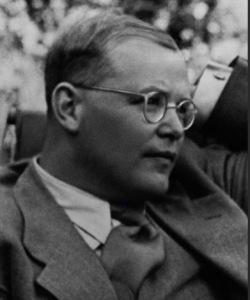

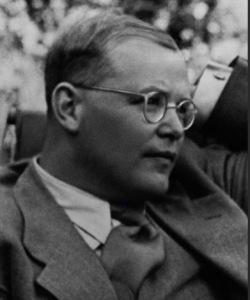

The German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote a reflection on this very question in a Nazi prison just weeks before he was executed for his opposition to the regime.

Who am I? They often tell me,

I come out of my cell

Calmly, cheerfully, resolutely,

Like a lord from his palace.

Who am I? They often tell me,

I used to speak to my warders

Freely and friendly and clearly,

As though it were mine to command.

Who am I? They also tell me,

I carried the days of misfortune

Equably, smilingly, proudly,

like one who is used to winning.

Am I really then what others say of me?

Or am I only what I know of myself?

Restless, melancholic, and ill, like a caged bird,

Struggling for breath, as if hands clasped my throat,

Hungry for colours, for flowers, for the songs of birds,

Thirsty for friendly words and human kindness,

Shaking with anger at fate and at the smallest sickness,

Trembling for friends at an infinite distance,

Tired and empty at praying, at thinking, at doing,

Drained and ready to say goodbye to it all.

Who am I? This or the other?

Am I one person today and another tomorrow?

Am I both at once? In front of others, a hypocrite,

And to myself a contemptible, fretting weakling?

Or is something still in me like a battered army,

running in disorder from a victory already achieved?

Who am I? These lonely questions mock me.

Whoever I am, You know me, I am yours, O God.

It is said that in prison, Bonhoeffer inspired all those who came in contact with him by his courage, his selflessness and his goodness, He even gained the respect of his guards, some of whom would apologise to him for having to lock the door of his cell. His calmness and self-control meant that he was able to give practical as well as pastoral care to his fellow-prisoners, saving some of them from certain death and bringing the comfort of his faith to many. This poem reveals, however, that, hidden inside, known only to himself, was a different person, weak and hurting, close to despair. He is tormented by the contradiction between the person others would say he was and the person he knows himself to be. He is unable to answer the riddle he has become to himself. He addresses his piercingly honest questions to God.

Jesus answers Simon Peter’s unspoken question by playing on his new double name. He is Simon son of Jonah, the most human of the disciples, struggling – and often failing – to understand Jesus and to follow in his way. He is also Peter, called to become the rock on which the new, world-changing community would be built.

Simon Peter is blessed, not through any virtue or wisdom of his own but because of his love of Jesus and his willingness to follow him. In the last line of the poem, Bonhoeffer’s tortured questions are answered in three simple words: ‘ I am yours’.

Are we, perhaps, being reminded today that blessedness is not about being perfect and free from contradictions, but about being willing to hand over who we are to God so that we can become the person God wants us to be?

You know me, Lord, and you love me just as I am. Help me to trust you enough so that I can freely offer myself to your service day by day. Amen.

Nerys writes: Today’s short Gospel passage, Matthew 15.21-28, centres on a marginalised woman who was so desperate for help that she would – and did – do anything to get to Jesus. Once more this week, we have heard on the news stories of people who are just as desperate for our help, due to war or persecution, due to the effects of climate change, due to the cost of living crisis, due to social isolation. Matthew’s story isn’t straightforward, however. In fact, it has been described by various authors as one of the most unsettling, awkward, puzzling, shocking passages in the New Testament. Let us explore it together, taking our time to reflect on how it speaks to us as the ones through whom Jesus chooses to respond to desperate people today.

Jesus had left the province of Galilee after a major clash with the Scribes and Pharisees, travelling north into the hills. We can imagine him pausing with his disciples in a highland village to get some peace and quiet and a perspective on his work and its effect. But even there, his reputation has gone before him …

A local woman comes, desperate for his help. Her daughter is being tormented by a demon. ‘Lord, Son of David, have mercy on me!’, she cries, hailing him as the Jewish Messiah, but Jesus doesn’t answer her. The Greek suggests she is screaming continuously. Yet it seems that Jesus is ignoring her. We can imagine him walking on with the woman running behind him until his disciples, upset or annoyed by the disruption, urge him to send her away. It’s only then that he stops to explain his silence, speaking of ‘the lost sheep of Israel’ as the only ones to whom he has been sent.

This woman is described by Matthew as a Canaanite which is odd because in Jesus’ day, the Canaanites, the former enemies of Israel, no longer existed as a people group. The point Matthew is probably making by using this term is that she is a Gentile, belonging to a people who worshiped strange gods and didn’t observe ritual laws of purity, a people who had long been excluded from the chosen ones of the God of Israel. And this is the issue around which the whole story revolves. His mission, Jesus insists, is to the Jews only. It is limited to God’s chosen family of faith.

Upon hearing his words , the woman moves quickly to block their path by kneeling in front of Jesus. She pleads once more, ‘Lord, help me!’ as she prostrates herself before him. (The Greek verb can also mean, ‘to worship’.) In his third response, Jesus rebuffs her again and this time, what he says sounds like an insult: ‘It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs’. A lot of ink has been spilled trying to explain this response but there’s no getting away from the fact that the term ‘dog’ is dehumanizing. It is clearly meant to be offensive.

Despite his harsh words, the woman holds her ground and answers him back, challenging the notion that she is outside God’s promises, insisting that her life and that of her child, matter. Even if Gentiles are ‘dogs’, she says, a dog may come near enough to the table to gather up the crumbs that the children spill and so share the same food as the family. Matthew gives her the final punchline in the story and on hearing it, Jesus commends her great faith and her daughter is healed.

Jesus’ behaviour is clearly out of character, his words are undeniably insulting, but without seeing his body-language and his facial expression and hearing the tone of his voice, it is almost impossible be sure how to interpret this encounter.

Some readers see this story as a unique example in the Gospels of Jesus changing his mind. They hold that Jesus, born as a Jew, would have grown up with a certain worldview. It would be natural for him to accept that Gentiles were to be excluded from the family of faith and even from the circle of those deserving compassion. They argue that the woman in her desperation pushes Jesus to do something he had not intended to do. It is her, and not Jesus, according to them, who is the hero of the story. She challenges his views, confronts his prejudice, opens his mind to new possibilities. It is her persistence and the sheer force of her faith, they say, that shakes Jesus out of his narrow Jewish perspective and brings him to a fuller understanding of the scope of his mission. He may have healed her daughter but she taught him what it meant to be God’s Son – not just a Jewish Messiah called only to the lost sheep of Israel, but the Saviour of the people of the whole world,

Others assume that Jesus knew precisely what he was doing and chose to use this chance meeting as a teaching moment for his disciples. He knew that this desperate woman had recognised something in him that even his own disciples had failed to see. So he set out to be deliberately provocative, challenging her by his hesitancy and his disparaging words, to display the quality of her faith. He reflects society’s attitude towards her but not his own, playing devil’s advocate with her with a twinkle in his eye, in the knowledge that she is a match for him. And she responds magnificently.

In the church for which the Gospel of Matthew was written, there were those who believed that Christianity was not for everyone, only for God’s original people. Conversely, in today’s Epistle, Romans 11.1-2, 29-32, Paul addresses the Gentile churches in Rome, who saw the Jews as a lost cause. In both these churches the Christian faith was at risk of being limited by cultural and racial boundaries. It continues to be at risk in our churches and in our lives today. It doesn’t matter how we interpret the conversation, this is a story about faith calling us, to widen our vision, to push old boundaries. to enlarge our hearts.

In today’s Old Testament passage, Genesis 45.1-15, we see Joseph’s faith in God being finally revealed as he forgives his brothers. It is this faith that enabled him to grow in wisdom and compassion to such an extent that he could embrace those who had plotted to kill him and sold him as a slave to Egypt. The call of faith is insistent like the Canaanite woman who wouldn’t leave Jesus alone. It led Jesus to the cross and beyond. It keeps after us, calling us by name, challenging our limited thinking, transforming out hearts so that we are prepared to respond to all who are in need of God’s love.

Loving God,

enlarge our hearts to see others as you see them,

engage our minds to remember that we are all your children,

encourage us to bring your love to others, especially those in need,

Amen.

Moira writes: This morning our gospel passage is taken from Matthew 14:13-21 and the illustration below shows us just what it’s all about. As you prepare for worship this morning, please read through the passage and hear what God is saying to you in verse 16, they need not go away; you give them something to eat.

Our Gospel passage this morning begins with Jesus receiving the news that John the Baptist is dead, and with a heavy heart, Jesus wanted to get away from the crowds to go to a quiet place. The crowds had been following Jesus as he travelled in towns and throughout the countryside, and they hung on his every word. Now Jesus needed some time to himself and no doubt he wanted to be alone to pray to his Father. We all know that when Jesus wanted to talk with his Father, he almost always went up into a high place where he could be alone, and this particular day it looks like he almost made it. Almost, until the crowd heard and began to follow him on foot. I’m sure we can all empathise with Jesus in his need to be alone to grieve over the death of his dear friend John. While it is good to have family and friends around when we are trying to cope with a death or even serious illness, there are times when it’s good to have some time to be alone and to pray. In chapter 13 of Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus had been rejected as a prophet without honour in his own town. Herod’s desire to kill John, which was inhibited by his fear of the crowds who regarded John as a prophet, is similar to the Chief Priests’ desire to arrest Jesus, which was hampered because, as it says in Matthew 21:46, they feared the crowds, because they regarded him (Jesus) as a prophet.

And so we find Jesus trying to withdraw from the crowds, not through fear of them like his opponents, but through the need to spend some time on his own in prayer and time with his disciples in teaching. But of course, the crowds had other ideas, they follow him and find him, and motivated by compassion, Jesus provides for them and heals them. It’s interesting to note here that Jesus is instantly drawn into helping those he sought to withdraw from. I think this is a situation that those in ministry and in pastoral care often find themselves in. The need to have some time to relax and refresh, and the sudden call of those who find they are in need of care. The passage continues as the disciples join Jesus, and by evening the situation becomes overwhelming, so many people, adults and children, who have walked for miles to be with Jesus and who now need to be fed. However, the reaction of the disciples is quite the opposite to that of Jesus. They see the crowds and ask Jesus to send them home because they are hungry and need to be fed, after all, the disciples don’t have much food themselves. They want the people to buy food of their own, but Jesus says to his disciples, they need not go away; you give them something to eat. You give them something to eat! A simple request, and yet impossible with so many hungry men, women and children needing to be fed.

So how did the disciples respond? We have nothing here but five loaves and two fish. Jesus is calling his disciples into action, but they seem to be hovering on the sidelines. ‘O ye of little faith’ springs to mind. This story looks to the past, a past when Moses led the people across the Red Sea into a wilderness, where they were fed with manna and quails, remembered as ‘bread’ in Deuteronomy and ‘food from the sea’ in the book of Wisdom. Here in our gospel passage, it’s Jesus who initiates this wonderful provision for the people, engaging his disciples in his work.

We can’t possibly fully understand the miracle that happened that day which enabled so many to be fed, but there are some things that we do know for sure. The disciples gave up what they had, Jesus gave thanks to God, the food was shared out, and there was more than enough. If we try to work through the mechanics of this miracle, it won’t get us anywhere. We will, as they say, be ‘barking up the wrong tree.’ Like so many stories in the Bible, we need to ask what we can learn from them. So, let’s start by reversing the order of the facts we know and have listed.

‘There is plenty of food available,’ it should be shared fairly, we need to be grateful for it and sometimes we have to give something up. Just think for a moment about the world food crisis and the food poverty in our own communities. These are overwhelming situations! When the disciples felt overwhelmed by the task of feeding the crowd and they protested, Jesus told them to do something; to get on with it. He wanted the disciples to use their own initiative and called them to action. If large supermarkets and suppliers can share surplus food with local food banks, and we do whatever little thing we can, then there should be plenty of food available and it should be shared fairly.

Remembering to ’give thanks to God’ for what he so graciously provides for us is something we often forget to do. Making it part of our daily prayer or at mealtimes, if this is our tradition, reminds us that God wants us to use our own initiative and that he calls us to action, asking that ‘we give up something’ to help others. In an earlier chapter of Matthew’s gospel, chapter ten, Jesus had summoned his twelve disciples and sent them ‘to the lost sheep of the house of Israel’ and so here in today’s passage, the twelve baskets of food remaining symbolises the fulfilment of God’s promise to the twelve tribes of Israel, you shall eat your fill and bless the Lord your God, found in Deuteronomy 8:10.

Our gospel passage also looks to the future, to Jesus’ last meal with his disciples, when he again took bread, blessed, broke and gave the bread to those around the table. In today’s story, he gave bread for the community when the crowd came together into the presence of Jesus, and the disciples renewed their compassion realising their capacity to feed the crowds. If Jesus hadn’t called his disciples into action that day, to help provide for the great crowds of people, they would have gone away hungry, and nothing would have been done. When we answer God’s call to action in our lives, great things can be achieved – and more. In today’s parable 5,000 people were fed from five loaves and two fish and there were still 12 baskets of pieces left over! In the life of our church today, we have the chance to be active Christians in the things we choose to do and the things we choose to support. The donations of food to a local foodbank, toiletries for the Ukrainian community, the hosting of Tea and Toast for mums and toddlers and many other projects we as a church support. The disciples in today’s story felt helpless in the face of a seemingly impossible task. Jesus tells them to do what they can with their limited resources, and these turn out to be ‘more than enough.’ We too are easily paralysed by the enormity of the world’s suffering. However, instead of getting caught up in the difficulties in our world, we might think of one small act of generosity to perform this week. This is the challenge I feel we are being set in this week’s passage from Scripture. Not to be inactive, but to be active in responding to God’s call to look beyond the great difficulties in our world and to make a difference, however small that might be.

They need not go away; you give them something to eat. AMEN.

Please pray

For those who are struggling to feed themselves and their families.

Give thanks to God for local foodbanks and charities.

For the young people in our community and in our churches during school holidays.

Give thanks to God for holiday clubs and community events.

For our Rector Nerys and our church family at St. Mary’s, giving thanks to God for the life of our church.

Nerys writes: A few weeks ago, I spent an afternoon at a friend’s art exhibition, learning how to be creative with my mobile phone. She showed me how to zoom in on details in ordinary things in nature and then encouraged me to try using different filters to enhance particular aspects of an image to produce interesting, artistic photos.

Jesus in his parables zooms in on ordinary things – a lump of dough, a treasure trove, a fishing net, a flock of sheep. Sometimes the writers of the Gospels will add a filter which creates a particular effect. Sometimes we the readers do that ourselves when we come to a parable with our questions, our fears, our hopes.

In Matthew 13.24-30, Jesus zooms in on a cornfield infested by weeds. An enemy of the farmer had sabotaged the crop. The servants are keen to take out the weeds immediately but their master prefers to wait until harvest. This situation would have been familiar to many of Jesus’s listeners. Roman law had a punishment for anyone who scattered the seeds of a particular weed in a neighbour’s cornfield. That weed was the bearded darnel, known also as ‘false wheat’. As it grows, its roots surround the roots of good plants sucking up precious nutrients and scarce water. Above ground, it looks just like wheat when young but when fully grown, it produces black seeds which cause hallucinations, blindness and even death if they turn up in the bread dough.

In Matthew 13.36-40, Jesus gives his disciples a detailed explanation of the parable, focussing on the harvesting of the wheat and the fate of the weeds. As the parable appears only in this Gospel, it’s difficult to know to what extent the author has coloured its interpretation with his own preoccupations. Elsewhere, Matthew is very keen on warning his readers about the final judgement when God will divide people into good and bad, faithful and wicked, blessed and cursed. His is the only Gospel that contains the wise and foolish virgins or the division of the sheep from the goats. It is he only who mentions the furnace of fire where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Was he perhaps addressing a growing concern within the church community to which he belonged, a concern shared perhaps by the readers of today’s Epistle? In Romans 8.12-25 Paul also makes a clear distinction between people: those who live according to the flesh who will die and those who are led by God’s Spirit who will live. He provides hope of a release from the Church’s present suffering by using the image of a woman in labour groaning as she gives birth to a new creation. A day will come, he promises, when the kingdom of God which Jesus had brought into the world, will finally be established and all evil and evildoers will be eradicated. In the meantime, the Holy Spirit will give the faithful what they need.

Matthew highlights the harvest but I doubt that this was the idea that would have most interested the crowd on the beach as they listened to Jesus. Most of them would have taken as a given the belief that a time would come when God would judge the world, dividing the faithful from the wicked. Like many Jews of the time, they longed for that day when they would be rescued from oppression and the enemies of their people would be punished. In Jesus they saw God at work bringing in the kingdom. They flocked to him eager to help in the process, probably assuming that it would be in the form of a military rebellion. They would have identified themselves with the slaves of the householder who are keen to immediately root up the weeds in the field. I wonder what their response might have been to the master’s insistence on waiting until harvest time? Would they have seen it as wisdom or folly?

When we look at the parable through the filter of today’s Old Testament readings, Genesis 28.10-19 and Psalm 139, it is the nature of the owner of the field that grabs the attention. Both authors paint similar pictures of what God is like. The psalmist emphasises God’s intense interest in every aspect of his life and God’s care for him. This is exactly what Jacob discovers, as he flees from his brother’s wrath. In his dream he learns that he is not alone. He hears God saying, ‘Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go’, The owner of the field, the one who planted the good seeds, is unwilling to take out the weeds because he doesn’t want to risk a single ear of the crop. He knows that their roots have become entwined with those of the weeds. The only way to avoid damaging the good plants is by waiting patiently until harvest time.

We long for the evils that lead to injustice, corruption and conflict to be uprooted. The parable reminds us how difficult a task this is. The reality is that our world, our communities, our families and sometimes our own lives are like the farmer’s infested field. It is tempting to seek to root out all evil whatever the cost but this isn’t God’s way. We are not called to be the ones who judge others or ourselves. We leave that work for our merciful God to do in God’s time. Rather, we follow the example of Jesus. Just before he tells this parable, the Pharisees try to trick him and begin their plot to destroy him. Jesus knows that they are as false and deadly as any bearded darnel but he is more interested in the growth of the wheat than in weeding out any weeds.

We are called to live with the evil that is among us and within us, patiently cultivating the good. We do this work through the power of the Holy Spirit, knowing that God has promised to be always with us and for us, and in the certain hope that God’s goodness and love will prevail.

“Let anyone with ears listen!” This Sunday as you prepare for worship, you may wish to read through the gospel passage for today Matthew chapter 13 verses 1-9 and 18-23. Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” This Sunday as you prepare for worship, you may wish to read through the gospel passage for today Matthew chapter 13 verses 1-9 and 18-23. Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word.

Today we hear about a farmer who goes out to sow seed. Nothing surprising in that, farmers sow seed all the time. Anyone who knows anything at all about what a plant needs to grow, won’t be surprised to hear that seed cast in the middle of a road, or on the rocks, or amongst thorns, doesn’t grow. However, there is something else so surprising that it should make us sit up and recognise the work of God’s spirit among us and in our world. We know it’s no surprise that the seed in this story, which was cast onto the road, into the rocks and amongst thorns didn’t grow. What is surprising is that the farmer chose to sow it in these places. This isn’t a rich man we are talking about, this is a poor tenant farmer who can only make a living for himself and his family if he not only makes wise choices about where to sow the seed, but also is blessed with good weather and a great deal of luck. Good seed was hard to come by and the wise farmer would make sure that his precious grain goes into the best possible soil. However, the farmer in our parable this morning tosses seed about while standing in the closest thing he can find to a car park at Tesco, where the pigeons will eat it if hundreds of feet and car tires don’t grind it into the ground first. In short, this farmer behaves as though this most precious seed was available in unlimited supply. What on earth is he thinking.

So now comes the real eye-opener, the second surprise in this parable. God blesses the farmer beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Normally a wise farmer who reaps a twofold harvest would be considered fortunate. A fivefold harvest would be a cause for celebration throughout the village and would be attributable only to the fulness of God’s rich blessing. But this foolish farmer who, in a world of scarcity as it was at that time, casts his seed on soil everyone knows is worthless and is blessed by God with an amazingly abundant harvest. God promises him a harvest of thirty, sixty, and a hundred times what he sowed. “Let anyone with ears listen!”

In this parable of the Sower and the seed, what we must remember is that the Kingdom of God was Jesus’ main emphasis in his ministry. It follows on from chapter twelve where Jesus finally broke away from the synagogue. The passage begins, “That same day Jesus went out of the house and sat beside the lake.” Matthews statement that Jesus went out of the house, actually points to the breaking away of Jesus from the synagogue in chapter twelve. He had ‘left the house’ so to speak because of disagreements with the religious leaders there. The crowd, mentioned in the next verse, represents those who were as yet uncommitted to any denomination or religion and who gathered to hear what Jesus had to say. And so, when Jesus began to speak about the Kingdom of God in his usual illusive way, it was hard to define exactly what the Kingdom was. Even his disciples were baffled and needed an explanation, which is why Jesus told the parable of the Sower and the seed.

We all know the story well, the Sower is God, the seed is the Kingdom and the various types of soil represents us, you and me. When we look at this story, it doesn’t sound as though God is a very frugal farmer. After all, most of the seed never takes root. But this is not really a story about the Sower and the seed, it’s a story about the different types of soil, or to put it another way, the different responses of the people to the message of Jesus about God’s Kingdom. The question for us to ponder is, what is the state of our hearts when the seeds are sown in us?

As we think about that, let’s examine the various conditions of the heart mentioned in this story. The hardened heart: These are the people who listen to the Word of God, but who are so caught up in their own lives, that they have no time to let the words sink in. They think they know best, and no one can tell them any differently, so they close their ears and their hearts.

The distracted heart: These people seem quite keen at the beginning to hear the Word and might even seem to be very excited about it. Then something else enters their lives and they forget the Word. They get caught up in whatever is the latest fad or attraction, and all their attention goes on this.

The defeated heart: People with defeated hearts are those who never really get the chance to listen to the Word. As soon as the Word is spoken, they have someone else whispering in their ear and telling them not to listen. They are easily defeated by others stronger willed than they are and who set out to lead them away from the Word.

And finally, the heart which I hope everyone here today has, The Hopeful heart: This is a heart that is filled with joy every time it listens to the Word of God. People who have hopeful hearts receive the Word of God through reading and listening to scripture. They are people who see the glass as being half full and not half empty. Those who accept the Word of God and hold to it firmly in spite of hardships or distractions, produce abundantly the ‘fruit’ of the Kingdom – that is to say, God’s will is fulfilled in their lives. We all have ears to listen, but do we always listen with joy and hold onto the Word so that we might spread the good news of God’s abundant Kingdom?

In our Gospel passage this morning, Jesus is not only talking about the Kingdom of God and how it is received, but about the growth of that Kingdom. So what is the message we need to hear from a story that suggests that God is like a farmer who tosses seed into car parks for the pigeons to eat, and in the surprising harvest that grows? I think that it says to us that Isaiah’s prophetic word, in our first reading this morning, is coming true. (You may wish to read Isaiah chapter 55 verse 1-2 and 10-13). In the first two verses of chapter 55 (which for some reason are not included in the lectionary), Isaiah says, “Ho, everyone who thirsts, come to the waters; and you that have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk without money and without price. Why do you spend your money for that which is not bread, and your labour for that which does not satisfy?” ‘Ho,’ in other words, Listen!

What we should realise is that the Kingdom of God has come among us, and we are encouraged to share it with everyone, regardless of who or what they are. Even seed that is sown on what is regarded as worthless ground is not worthless to God. He can and will bless the seed that is sown in everyone’s hearts and will encourage a response to come forth. God has blessed us richly, and God’s people, you and I, have been entrusted with the seed of God’s Word which is the most precious in the world. Ironically, these priceless commodities only gain value – the seed of God’s Word only bears fruit – when God’s people scatter it absolutely heedless of who they think is worthy to receive it. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Amen.

Some reflections for prayer:

Thank God for his abundant blessings in our lives.

Ask God to give us courage to spread the good news of his Kingdom to all we meet.

Pray for God’s harvest to be shared equally among all in every part of our world.

Pray for ‘fertile soil’ to receive the Word of God and to respond to it.

And may God bless you abundantly this coming week.

Moira

Peter writes: As Nerys said last Sunday, in spite of their happy endings, these episodes from the life of Abraham contain elements that we, some 5000 years later, find unacceptable.

There is his refusal to allow Isaac to marry outside his own ethnic background in today’s reading, Genesis 24.34-38, 42-49, 58-67. Thinking of my own lovely daughter-in-law of Chinese heritage, I have to ask “What is wrong with that?” Then there is the way the bride was chosen and the fact that she was brought from another country. In our culture we tend to disapprove of arranged marriages. In the Church of England nowadays, clergy have to check very carefully before calling banns of marriage – is it a forced marriage or an attempt to evade the ever-stricter immigration laws?

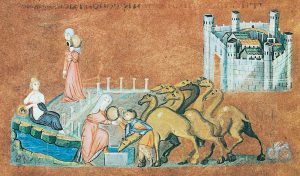

Rebecca at the Well, Vienna Genesis, 6th century

Even worse in our eyes is the fact that Abraham owned many slaves and this was regarded as a source of pride. Slavery in the ancient world was often a consequence of poverty and his female slaves had probably been sold to him by their fathers. Nevertheless, historians tell us that slavery at that time was nothing like the shameful brutal and cruel treatment suffered by African slaves in America and the Caribbean. In fact, masters could be prosecuted if they mistreated a slave. Their situation was perhaps more like that of farm labourers or domestic servants in this country in the 18th and 19th centuries.

So we need to view the past – whether biblical or otherwise – through the lens of history; if humans are still around in 5000 years, what will they make of our attitudes and cultural norms?

Turning to Paul’s letter to the Christians in Rome, the psychological state he describes in Romans 7.15-25, could be compared with slavery. He calls himself a “captive”, who cannot help himself from doing what he knows to be wrong and is unable to do what is right. Like a slave, he is being coerced and elsewhere in his letters he talks of being enslaved. Similarly Jesus describes the reaction of his listeners with that colourful metaphor: “We played the flute to you and you did not dance; we wailed to you and you did not mourn”. Like slaves, our freedom of thought and action is fettered and in Paul’s view there is little we can do about it because we are “in the power of the law of sin”. In the words of Private Frazer in Dad’s Army, “We’re doomed!”

Or are we? In the ancient world many slaves were often freed after six years or for other reasons. Paul’s listeners would have known this and would readily understand why he wrote “Who will rescue me from this body of sin? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!”

Hints as to how he could write this are contained in today’s reading from St Matthew’s Gospel, 11.16-19, 25-30: “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens” – slaves in their day were not allowed to be overworked – “and I will give you rest” – slaves were entitled to Sabbath rest and in the age to come we shall all rest from our labours. “For I am gentle and humble in heart”. This is the same example for Christian living as “Blessed are the meek, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven”.

It is not a pattern based on the many burdens imposed by the many and petty rules of the “wise and intelligent” but on the simple rule of “Love your neighbour as yourself”. This is Jesus’ easy yoke revealed to babes and infants.

FOR PRAYER AND REFLECTION

We pray to the Lord, whose service is perfect freedom –

for couples preparing for marriage and those married recently; that in binding themselves one to another they may find fulfilment and joy;

that those who think themselves wise in the world may learn to trust the wisdom of the simple;

for the victims of people trafficking and modern slavery; for organisations working to release them from their situation; for countries still bearing the burdens of past slavery;

that we may be more gentle and humble in our dealings with others, giving them relief from their burdens;

for all who are bearing the heavy loads of poverty, war, oppression or the weight of unresolved sin;

for those we know who are wearied through illness or sorrow; that they may find comfort and relief;

for the departed, that they have laid down their burdens and found eternal rest.

Nerys writes: I hope you’re ready for a challenging read this week because none of our Bible readings are straightforward. Each one is quite difficult for us as modern Christians to relate to, being not only textually difficult but also spiritually and ethically challenging. Some churches will have chosen not to include the story of Abraham and Isaac in their services today but I think it’s important that we don’t shy away from passages like these but learn ways of approaching them. It is clear that none of them are to be read unthinkingly or uncritically or taken at face value. We have to make a real effort to prayerfully discern what they might be saying to us about the God we worship and how we are to live our faith and communicate it with others.

Despite its happy ending, the tale of the near-sacrifice of Isaac on Mount Moriah, Genesis 22.1-14, is one of the darkest and most disturbing of all Bible stories. It is a story which horrifies us and leaves us with many questions. Why would God instruct a father to kill his own son? Why was Abraham ready to go along with it? What about the effect of this experience on the child? What about Sarah, the mother who is left behind? And most importantly of all, what is this story saying about our God and the nature of our faith?

Generations of Jewish and Christian scholars, artists and poets and ordinary readers of the Bible have grappled with this passage. Some have sought to make sense of it by filling gaps in the narrative in imaginative ways, some have read it metaphorically while others focus on its historical and literary context. It’s possible that somewhere in its background lies teaching about human sacrifice, a practice forbidden and regarded with horror in ancient Israel. The story as we now find it, though, is introduced as a test of Abraham’s obedience to God. It can, in fact, be seen as a culmination of a series of tests experienced by Abraham and a key part of the larger story of God’s relationship with the people of Israel. In the Jewish tradition this passage is read daily as part of the morning service. Early Christians saw what God was calling Abraham to do as a sign of what God himself intended to do, sacrificing his own son for the sake of the world. For many, this story prefigures the Cross. For others, however, the life, death and teaching of Jesus reveal a faithful, loving, self-giving, self-sacrificing God, not one who demands blind faith and the sacrifice of the lives of others.

However hard I wrestle with it, I am, unlike artists like Domenico Zampieri above, unable to turn this chilling story into something beautiful and uplifting. At every reading I am also left with more questions than answers. And yet within it and through it, I hear the call for us to trust God rather than depend on ourselves and on earthly things, and I am given assurance that God provides for us in even the most unlikely and darkest situations.

Today, the idea of slavery is just as alien and abhorrent as the idea of human sacrifice. In Paul’s day, many of the people of Rome including those he was addressing in our epistle, Romans 6.12-23, would have been either slaves or freed slaves. For them, the image he uses to describe what coming to faith is like would have been acceptable and meaningful. For us who see slavery of any kind as immoral and unjust, it is troubling. Instead of picturing the process of becoming a Christian as that of being set free, Paul describes it as a change from one slave master to another. His argument that human beings will always be enslaved to someone or something is challenging for us who believe that we have a measure of self-control and self-determination. The thought of being God’s slaves is uncomfortable. It would be easy to dismiss this passage as a response by Paul to a particular concern of the churches in Rome. And yet, if we look beyond the imagery what we see is another invitation to trust God rather than depend on ourselves and on earthly things. We also find an assurance that when we choose to give our whole selves to God’s service, God will provide. God will give us the grace to live a life of joyful obedience which leads to an incomparable freedom to be the people we are meant to be.

Our Gospel passage today, Matthew 10.40-42, is a mind-twister as well as a tongue-twister. It is part of a longer story of Jesus preparing his disciples as he sends them out into the towns and villages of Galilee to proclaim that the kingdom of heaven has come near. Having given them his authority to heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers and drive out demons, he speaks hard words about the need for absolute loyalty and commitment in the face of division and persecution, of losing life in order to find it, of taking up the cross to follow him. Then he gives words of encouragement and comfort: ‘Whoever welcomes you welcomes me and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me’. His disciples will be sent out as envoys of Jesus, coming in his name, on his business. To offer them help and hospitality is just like offering it directly to him who is God’s envoy. And God will reward those who support their work, even if it’s with something as little as a cup of cold water. The apostles may well feel small and vulnerable but God is watching over them and will provide for them through the goodness of the people they will meet on the way.