Rachael writes: Almost forty years ago now there was a disaster at sea. The doors of a ferryboat failed to close as it left the dock and water poured into its car decks. It listed to the side and panic began to set in amongst the passengers. The jovial atmosphere of a boat full of holidaymakers quickly turned into something more like a scene from a nightmare.

But in the midst of the chaos a man – an ordinary passenger on board – stepped up to take charge. With an authoritative tone he took command and gave instructions. People paid attention to him and, despite their underlying fear, were calmed enough to make their way to lifeboats that they otherwise would have missed in the crushing darkness.

The man himself made his way to the lower decks and to those trapped in the hold. The boat was now capsized, lying half submerged on a sandbank. People were trapped but the man created a human bridge with his body, creating a way across a damaged walkway by holding on to a ladder with one hand and another part of the ship with the other. Twenty people who would otherwise have drowned climbed across him to get to safety.

When the nightmare was over, the man was given a special honour for his bravery and selflessness.

Our story from Mark (1.21-28) takes place on a different coast, that of the Sea of Galilee (which is actually a lake), in the little village of Capernaum – population of maybe 1500 people in the first century. In the synagogue there, whose ruins you can still visit today, a man who nobody really knows and who certainly isn’t one of their usual preachers, begins to tell people what God’s will is, apparently all in his own authority. He didn’t caveat it with things like “as Moses said” or “as such-and-such said”, he just laid it out as he saw it with a quiet but compelling authority.

And in that same authority he speaks words of healing over those in need. Tom Wright describes those who came to Jesus as “people for whom life had become a total nightmare – whose personalities seemed taken over by alien powers”. The original audience of the gospel would never have questioned whether demons exist or whether healing was possible – the manipulation of the physical and spirit world isn’t the point that Mark is trying to make, nor is it Jesus’ aim either, because what his miracles symbolise is so much more important. Jesus has come to stop the nightmare: to rescue people (both nations and individuals) from the destructive forces that enslave them. And he’s going to do it by relationship and trust, not power grabbing or domination. He’s come to forgive sins and set people free from guilt, fear, and shame. God is changing everything, and changing forever the conditions in which human beings live. So whether its shrieking demons who accost him in the synagogue, a woman with a fever, or any other kind of disease that they bring to him, Jesus deals with them all with compassion and the same gentle but deeply effective authority.

It’s all part of how Mark shows us who Jesus is, especially in this very early depiction of his authority to set people free. It’s all part of Mark’s introduction to Jesus’ purpose and agenda. First, he shows Jesus to be the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy, then John the Baptist announces the coming of one who is stronger than him who will baptise with the Spirit, and straight away, in his baptism, Jesus is proclaimed as the Son of God. He’s then tempted by Satan before gathering together fishermen who immediately leave everything to follow him who knows where, because he just has that much authority! And then, as if we needed any more convincing, in the synagogue, at the heart of the provincial Jewish social order, in the very seat of the Establishment’s power, Jesus breaks down the boundaries and enters into a struggle against the forces of evil and destruction which, like the cruel sea pouring in on top of helpless passengers, seem to be engulfing all before them.

Mark is pointing, right here at the beginning with fifteen chapters to go, to the dramatic conclusion of Jesus’ ministry upon the cross. For it is on the cross, and not in power or miracles or scholarly debates, that Jesus calls out things for the way they really are and begins changing everything.

There, Jesus becomes the human bridge across which people climb to safety – with outstretched arms carrying people from death to life, from captivity to freedom. The man on the boat walked away with a medal but for Jesus the price of this saving authority, of this freedom for humanity, is his own life. The demons took their final shot at his authority as he hung on the cross but there he completed the healing, releasing work he began that day in the synagogue at Capernaum. There, as the sun grew dark and the temple curtain was torn in two, the centurion proclaimed “the Son of God!”.

We – created in the image of God, carried from death to life by Christ, and filled with the power of the Spirit – can be reluctant to walk in that same authority, despite the similar demons and nightmares that we find ourselves facing. The demons of illness, the nightmares of poverty, the horrors of hatred and war. The torments of greed and racism. They are similar, but not the same. Because, while they can still shriek, since Christ opened his arms to us all on the cross and burst forth from the tomb with arms still outstretched towards us, the demons no longer have authority in this world. We have been set free from their power and influence.

And that is what we share with our world: a steadfast resistance to the panic, fear and despair, saying “You have no authority here”.

Posted by Revd Rachael Wright on 19th December 2023 Rachael writes: “Who am I?” A philosophical and existential question – one that many of us will have asked ourselves at some point in our lives – that in each of our passages today, receives a concrete answer.

Hearing our passage from Isaiah (61.1-4, 8-11) we might find ourselves transported to the synagogue in Nazareth on the Sabbath day, when Jesus is handed a scroll of scripture and opens it to this passage, reading it before the gathered crowds and essentially saying to them, “This is me”. So, of course, when we read the text in Isaiah we can’t help but think of the narrator as Christ and, in the midst of advent, as we await his arrival, of ourselves as the audience. Jesus is coming to bring me comfort and to turn my mourning into joy.

In the second half of the reading in, this first person speaker takes on another role, becoming an agent for justice. The audience for the speech disappears, and the focus turns to the exaltation of the this paragon of righteousness. The target audience in the final verse is no longer the restored community, but the foreign nations – that is, outsiders.

Our context gives us fixed ideas about where we stand in the text but on its own it doesn’t really lend itself to that. Is the speaker, the “I” of the poem, our avatar, or are we “they” whom the “I” addresses? At first glance, it might seem obvious. The speaker cannot be me, because I could not do the things that God commands the speaker to do. I cannot declare release from suffering or change mourning into joy. It is much easier to be “them,” part of the passive recipients of God’s blessings. My life is hard, I want to yell. I am mourning! I am imprisoned by poverty/poor health/addiction/anxiety. God must surely have finally heard my prayer and come to bring me my just reward!

But note that the workers, the “they” of verse 4, are the oppressed, the brokenhearted, the captives, the prisoners, those who mourn. That is, the subjects and agents of the promised rebuilding are those who have been defeated. It is the “they” who were defeated who will rebuild. The people will take part in their own restoration.

John the Baptist (John 1.6-8, 19-28) is essentially asked three times, “Who are you?”. He begins by making it very clear who he is not: not the Messiah, not Elijah, not the prophet. It’s an important reminder to us, that we are not God. We are not Christ. John says that he is one called to testify to the light. He is the voice crying out in the wilderness. And similarly, the actions that we take and the words that we speak, the restoration that we participate in, must point back toward the light and avoid being so heavily associated with us that the primary star is miscast. In community also, the action that we take as a body of believers must point back toward the light, lest “St Mary’s” become more noteworthy than the Jesus we profess to profess.

But how do we do that? Well, once again Saint Paul, in his letter to the Thessalonians (one of the earliest Christian texts to be written, around 52AD) (1 Thessalonians 5.16-24), gives us a little gem of a mandate. These are the final lines of his letter, his last charge to the church in Thessalonica. His little ten point plan for them – you can feel the urgency! It actually immediately follows verses about Christ coming like a thief in the night, an allegory which we’ve heard twice already this advent. So it’s an answer to the question of, who are we as we await Christ’s return?

We are a people who rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances – not because there are no hardships but because even in the midst of them, God is with us. We are a people who do not quench but rather listen to the Spirit by paying attention to the prophetic, to wisdom and teaching, testing them together and holding onto what is good. In doing so, we abstain from the evil of falsehoods and those who wish to prey on a vibrant community of faith. Then our spirits, souls, and bodies, will be sound and blameless when Jesus gets here. We cannot do this on our own – God will do it in us.

Who are we? Ultimately, we, like the Thessalonians before us, are to live joyfully. Not closed off from the world but part of it, transformed by Christ. We are to be voices in the wilderness, witnesses who testify to the light, bringers of good news, proclaimers of liberty, displaying God’s glory, and building up and repairing the devastations.

And note that the question has changed. Not “who am I?” but “who are we?” for we can do none of this alone, we are united to one another through Christ, and together we joyfully serve him.

Our whole beings shall exult in our God.

Here this verse from Isaiah again:

“I will greatly rejoice in the LORD, my whole being shall exult in my God; for he has clothed me with the garments of salvation, he has covered me with the robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom decks himself with a garland, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels.”

We wear all of this joy like our best loved outfit. I’m sure you know the one. You can remember the day you bought it – browsing the rails, spotting it and wondering if it might be the one you’ve been looking for. Pulling it out and looking it up and down, trying to picture it on. Getting to the changing room and not daring to hope that your search is over. A quick look over your shoulder in the mirror as you do it up. Do you remember the way the fabric felt, the vibrancy of the colour? Do you remember how you stood when you wore it, the little turn you did to feel the movement of it? Remember how it made you feel, the confidence it gave you – shoulders back, head high, knowing you were beautiful and handsome. And that was before you even got out the door. Then you met with friends or family and, after that initial angst that others wouldn’t see it like you do, your confidence returned and you would tell anyone and everyone that it was a new outfit, from such and such a shop, that you got at this extortionate or bargain price. Everyone, even without you having to say anything can tell that you feel glorious. There’s a light radiating from you. You emanate joy.

If we wear God’s love in the same way, who will ever need to ask, “who are you?”

Rachael writes: I heard a story this week about a church youth group. On this particular evening their leaders had planned a hunger feast for them. It’s an object lesson in fairness and equality, and really in economics. The young people were to be divided into four groups. The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on. The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on.

No matter how hard the leaders had tried to squash such behaviour, she was left out on purpose and made fun of for what she wore and how she talked. When she pulled out the card for this fabulous tray of food, the rest of the group were annoyed and grumbly. A couple of girls even pulled a leader aside and said “It’s not fair that she gets everything, she’s so weird”. Some were even heard to say that she didn’t deserve it but that it should surely go to the cool people. While the adults in the room whispered to each other that justice had finally been served.

But the girl, sitting by herself with this beautiful spread in front of her, had tears streaming down her face. “It’s not fair,” she said. “I don’t like it. It’s not fair that no one else gets this and they should”. The leader asked her what she would like to do and after thinking for a few minutes she got up from the table with her platter and began to go around the groups making each person a sandwich from her board of goodies. There was an awkward and uneasy silence as people began to eat. Finally one person asked the girl “Why did you do that? We’re kind of mean to you all the time. If I were you, I would have eaten it all myself”.

And in the most eloquent moment, the girl stood before them and said, “You’re right. You’re not very nice to me and sometimes that really hurts. But Jesus reminds me that we love each other all the time. It doesn’t help me to keep this for myself but I want you to be a part of this party with me. The pastor tells us that everyone is invited to communion and think this is the same thing. I know what it’s like to not be invited and don’t want anyone else to feel the same way. So, sandwiches for everyone! Because God loves me, and you.”

Out of the mouths of babes…

This young girl understands the heart of the Kingdom of God. She knows what it means to live under the reign of Christ, and to participate in the world with Christ as your King.

We adults can become so jaded. I remember being 17, 18, 19, and thinking that I was going to change the world. But we get worn down by the heaviness of responsibility, by the need to just get through the day, by the constant stories of injustice and inequality, so that we start to think that change will never happen. That there will always be those who share the bowl of rice at one end and those sitting with the platters of luxury at the other – and nothing will change that. This girl, however, first of all uses her own experience to shape her response and to lead her to compassion. It could, as one of the others said, have taken her to bitterness and selfishness but instead she is moved to empathy. Then she turns that heartbreak into action – radical, selfless, courageous, and risk-taking action.

Which is exactly what our passages today point us towards. It’s interesting to me that on Christ the King Sunday we’re not given a vision of Christ in glory reigning over us but of an upside-down, inside-out, transformative Kingdom. We are given somewhere to believe in.

I wonder if you’ve ever been to a place and thought “this must be what heaven is like”. Maybe it was sunshine and white sandy beaches. It might have been a particularly excellent meal. I can think of a few myself – one being a vista at the top of an Italian mountain that brought me to actual tears; another being the festival that we go to in the summer, Greenbelt.

There, sharing communion with 9,000 people from all walks of life and all kinds of church backgrounds, with the elderly and tiny babies, with goths and bishops, with people in wheelchairs and people bedecked in rainbows and glitter, I feel like I get a tiny glimpse of what heaven, of what the Kingdom, might be like. The festival’s tag line is “Somewhere to believe in” (I even have it on a t-shirt). And I think that we all need to know where we’re going, what we’re aiming for, and as good as Greenbelt might be, as beautiful as those mountains and beaches were, or delicious as that meal was, the descriptions in Ezekiel and Matthew are better. They tell us of a place where freaks are ushered in, the famished are lavished upon, the vulnerable and shamed are wrapped up in love, and the light goes to dwell with those in darkness.

I remember, as if it were yesterday, the first time I read this passage when I was fifteen. It transformed my understanding of what it means to follow Christ and it continues to challenge me that walking with Jesus isn’t about “nice” or “comfortable” or “gentle”, but about radical, counter-cultural, and courageous love. Love that is risky. Love that is action. Love that is faith, in word and deed.

Let me encourage you, fellow sheep of the fold, to keep going. To continue to see Christ in everyone you meet. To open your hearts, your homes, our church, to those on the margins and in need. To keep your compassion and your courage. Have in mind the somewhere we believe in and, by God’s grace, may we see glimpses of it in the here and now. Amen.

Rachael writes: I heard a story for the first time this week: the ancient Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, although I have learned it as it is retold in the Broadway musical “Hadestown”.  Orpheus is a young singer-songwriter, madly in love with Eurydice. They’re a penniless couple and as winter arrives, Orpheus’ fixation on his song writing leaves Eurydice hungry, tired, and desperate. She is found by Hades, the King of darkness and shadow, the King of the underworld, who convinces her to enter the underworld with him where she signs her life over to him. Immediately she begins to lose herself among the indentured masses of Hadestown. Orpheus of course realises what has happened and takes a very long road to the underworld. He finds her there, but Hades is reluctant to let her go eventually agreeing that they may leave on one condition: as they go along the dark, winding road, over the wall and back to the surface, Orpheus must walk in front while Eurydice walks behind him. And Orpheus must never look over his shoulder to check if she is there, or else she’ll return to Hadestown forever. In the musical Orpheus asks his mentor Hermes whether it is a trick. Hermes replies, ‘No, it’s a test’. They begin the long journey but over the singing of the masses of the underworld Orpheus cannot hear footsteps nor Eurydice’s voice. He has no idea whether she’s there. They persevere until just as Eurydice sings that she can see the light and this is almost all over, Orpheus loses his nerve and turns round. He sees Eurydice there with him and he knows that he has condemned her to an eternity in Hadestown. Orpheus is a young singer-songwriter, madly in love with Eurydice. They’re a penniless couple and as winter arrives, Orpheus’ fixation on his song writing leaves Eurydice hungry, tired, and desperate. She is found by Hades, the King of darkness and shadow, the King of the underworld, who convinces her to enter the underworld with him where she signs her life over to him. Immediately she begins to lose herself among the indentured masses of Hadestown. Orpheus of course realises what has happened and takes a very long road to the underworld. He finds her there, but Hades is reluctant to let her go eventually agreeing that they may leave on one condition: as they go along the dark, winding road, over the wall and back to the surface, Orpheus must walk in front while Eurydice walks behind him. And Orpheus must never look over his shoulder to check if she is there, or else she’ll return to Hadestown forever. In the musical Orpheus asks his mentor Hermes whether it is a trick. Hermes replies, ‘No, it’s a test’. They begin the long journey but over the singing of the masses of the underworld Orpheus cannot hear footsteps nor Eurydice’s voice. He has no idea whether she’s there. They persevere until just as Eurydice sings that she can see the light and this is almost all over, Orpheus loses his nerve and turns round. He sees Eurydice there with him and he knows that he has condemned her to an eternity in Hadestown.

Orpheus tried but couldn’t help himself. He had to look back. Just like in our Gospel reading (Matthew 20.1-16) where the labourers who, when handed their wages, have to look at the other guys and say, “Hang on a minute”, rather than simply looking in their hand and being grateful, or even thinking of the possibilities ahead of them. And just like the Israelites on their desert journey (Exodus 16.2-15) who could not focus on the freedom of the moment or on the promise of God for the future, but had to look back and down the bitter road.

Both passages give us a vision for a future which we can be so reticent to look to – the equitable distribution of bread and meat throughout the wilderness congregation, and the extravagant equity for all on the landowners payroll. I wonder if we too will exclaim “This isn’t fair!”? Perhaps in the same way that we do in conversations around benefits, bonuses, and citizen’s wages? Because ideas of fairness, of “just deserts”, are the Hadestown that we are trying to walk out of but can’t help ourselves in looking back to.

There is no commandment to be fair, nor is it a spiritual discipline or a fruit of the spirit. It’s a human construct that attempts to masquerade as justice. Fairness pretends to treat everyone the same, where justice makes everyone whole. Fairness pretends that everyone is equal, while hospitality acknowledges that we are mutually dependent on one another. Fairness pretends we have equal access to the resources that meet our needs, while generosity proclaims that we never lose when we share our abundance. These tales of abundance make it clear that fairness lies behind and that God promises something much richer ahead.

The parable of the labourers sits between two bookends: in Matthew 19:30 Jesus introduces it by saying, “But many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.” Then he concludes by saying it again in Matthew 20:16—“So the last will be first, and the first will be last.” Jesus is saying God’s abundant grace threatens to upset the predictable seating arrangement: to turn the world upside down and inside out— or rather, turn it right side up and outside in.

It means that those of us used to the privilege of wealth and choice, must restrain our consumption. We must advocate and campaign with those who are don’t normally get a seat at the table, even giving them ours. We use our votes and our voices to implore rich nations like our own to pay for the loss and damage inflicted by climate change in the global south. We lobby our MPs to hold our backwards looking government to account, insisting that they re-impliment plans to scrap new petrol cars and gas boilers, and to enforce energy efficiency regulations in the rental sector, so that we achieve net zero by 2050. We keep our eyes fixed on Christ who leads us to an abundant, grace-filled future.

God isn’t out to test us like Hades and doesn’t hide behind us but actually gives us a very real foretaste such a future in the Eucharist. We all come in the same way and receive the same thing. No matter our status or the state of our bank account. Here, we get everything we do not deserve and it is intentionally “unfair”. Here, we are the labourers and the desert dwellers invited to Christ’s feast of radical hospitality and grace.

In a hopeful moment near the beginning of the musical, Orpheus offers a toast to Persephone – the goddess of spring growth. And I leave you with his words:

“Persephone who has finally returned to us with wine enough to share

Asking nothing in return except that we should live

And learn to live as brothers in this life

And to trust she will provide

And if no one takes too much

There will always be enough

She will always fill our cups

And we will always raise them up

To the world we dream about

And the one we live in now”

Rachael writes: At the burning bush, Moses is called to make a change (Exodus 3.1-15). He’s essentially been in hiding in Midian, enjoying the quiet and humble life of a shepherd and raising his family in relative safety. He knows the plight of his fellow Israelites but he has left them behind. Perhaps it seemed too big a battle for one person, especially one whose self-confidence is non-existent and who describes themselves as “slow of speech and slow of tongue”.

It’s the perfect story to start the season of creation with: the burning bush (forest, home, town) is an image that we are sadly now all too familiar with. In Hawaii, Canada, Greece, Kazakhstan, Chile, even here in Scotland. Millions of hectares, hundreds of lives. Each one is a reminder for those of us living in relative safety of the plight of the planet. The battle can seem too big for any one of us, even a small group of us, especially when we doubt the power of our own actions and voices, when we think of ourselves as slow of speech or tongue. But we too are being called to make a change.

God says to Moses, “I have observed the misery [and] heard their cry on account of their taskmasters”. “Who am I that I should go?” Moses replies. “I will be with you” God assures him.

What precisely does that call look like for us in 21st century Scotland, facing the issue of global environmental catastrophe, rather than one man 1000 – 1500 years before Christ going head to head with the ego of a despot?

It’s not a new call. Actually, we really need to rediscover the calling given us at our creation, as part of creation: our calling to serve. Humanity was ordained not to be masters or even custodians (that’s God’s job) but to be the servants of creation. To till and keep the earth. Not abuse or destroy it for our own gain. Somewhere (that we might call The Fall) we lost sight of that. Where we should have been servants, we thought ourselves masters. Where we should have grown a garden, we made ourselves gods.

The Office for National Statistics figures show that the median annual income for a man in 1973 was just short of £2000. The average price of a house in June that year was a little over £8000. Today the average annual salary is about £20,000 and the most recent figure for the average house price in the UK is £286,000. And our expectations of those very expensive houses are very different to 1973. Not just a fridge freezer but a spare freezer in the garage for a rainy day. A TV, not just one but one in almost every room, with not just 3 channels but 100s plus every streaming service going. Central heating in every room. At least one car, probably two, on the driveway. And many of us expect to leave that home on holiday for a week or so, multiple times a year, and on at least one occasion to go abroad. We add smart devices, robot lawnmowers, and self-cleaning toilets. We have guest rooms that we pray no one asks to use because we have a permanent guest called Clutter and their friend, Extra Storage.

Desmond Tutu once wrote “The taste of “success” in our world gone mad is measured in dollars and francs and rupees and yen. Our desire to consume any and everything of perceivable value – to extract every precious stone, every ounce of metal, every drop of oil, every tuna in the ocean, every rhinoceros in the bush – knows no bounds. We live in a world dominated by greed. We have allowed the interests of capital to outweigh the interests of human beings and our Earth.”

The only counter to such greed, to such consumption, the only thing that can save the planet now, is restraint. This is the new cost of living: to deny ourselves. For what will it profit us to gain the whole world, but forfeit our life?

Jesus tells us to set our minds on divine things, not human (Matthew 16.21-28). And if we set our minds on the Divine Christ, we see again that same call. For Christ came not to be served but to serve, to lay down his life for his friends, to make himself nothing and take on the nature of a servant.

There are two things I think that looks like at this time. The first is to realign our thinking so that human flourishing looks like compassion and altruism and community, not growth of numbers, productivity, or money. The second is to truly inhabit such thinking and find a way to give away what we have. To tithe, to share. To live out of abundance and generosity. John Bell, of the Iona Community, said at Greenbelt that for years he has had a note stuck to his front door which he sees every time he leaves the house and that it says “Give something away today”. And he has, every day. And he’s never missed a single thing.

Life is not found in what we possess. The more we buy, the more we are bought. But life is found in what we give. What will we give in return for our lives and the life of the planet?

We pray:

God Most High, maker of heaven and earth, you created humankind in your own image and entrusted the whole world to human care: give us grace to serve you faithfully, that we might be trustworthy stewards of your creation, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Posted by Revd Rachael Wright on 13th August 2023 Rachael writes: Many of us will know the trials and tribulations of sibling rivalry. Even last Sunday afternoon, as my brother and I (30 and 32 years old respectively) were taking some things from the rectory to the church hall, my dad walked off saying “I’ll leave you two to it, you get on better without us around anyway!”. It is simply an accepted fact in our family now, after years – decades even – of childhood squabbles, and teenage stand offs, that if we’re not vying for mum and dad’s attention, my brother and I can actually get on quite well. So, forgive me if I am projecting my personal experience too far but I do believe we’re not the only ones and that many, if not most, families experience this kind of tension between siblings for their parents’ attention and affection.

Joseph and his brothers, however, take it to another level (Genesis 37.1-4, 12-28). I can’t say I’ve ever actually thrown my brother into a pit, nor sold him to passing traders, though the thought may have crossed my mind at times. But such is the brothers’ animosity towards Joseph that they want to kill him and end up selling him off as a slave!

The lectionary means that we are going to cut thirteen chapters of Genesis, and a two-hour Andrew Lloyd Webber musical mega-hit, into two brief readings. We’re going to miss out the baker and the butler, potipher’s wife, dreams of famine and plenty, and next week jump straight to the brothers standing before Joseph, begging for food and their lives. We miss out decades of his life, decades that he spends in a kind of wilderness, as a foreigner with no status, cast out from his family and away from his land. Remember, he is seventeen when his own brothers fake his death and sell him as a slave.

I see some similarities between Joseph and Peter (Matthew 14.22-33). They’re both gifted, though perhaps not always wise. They are both destined for great things but need a little refinement before they get there. And in both stories that we hear about them today, they end up in the wilderness.

We often admire Peter, first because he has the faith to get out of the boat and then because he falters and starts to sink. We take comfort from “The Rock” on whom Christ will build his Church having a moment of weakness, knowing that we would likely go the same way.

Often, we skim over the fact that Peter steps out on the water while the storm is still raging around him. Sunday school pictures of a serene, lightly glowing Jesus, gliding like one of Dr Who’s daleks don’t help. Peter gets out of the boat into a wild sea. Into a literal wilderness.

I suspect that, like sibling rivalries, I’m not overstretching when I suggest that most of us know what it is to experience a personal wilderness. Whether it’s a bleak and inhospitable period, or a time of turbulence and disorder, like Joseph and Peter most of us have had to go there at some point, perhaps frequently, perhaps we find ourselves there now.

Eugene Peterson, pastor, author, and bible translator, calls his own experience of this “the Badlands”. He describes it as a kind of malaise, a featureless aridity, as if the colour had drained out of the vocation he had been so passionate about and the congregation that had been so full of life. But as he comes to terms with this period in his life and ministry, he says of it “there is a Badlands beauty that can only be perceived in the bad lands”.

The over arching theme of our readings at the moment is getting involved in God’s work in the world, in being part of the growth of the Kingdom, the transformation of all things, the redemptive work of the Spirit. But sometimes, especially if you’ve been working hard at it for a while, the fire within you which once spurred you on, can become dim – it may even flicker out. Sometimes we can identify why we end up in the wilderness, and sometimes the Badlands feel as though they’ve crept up on us. And we can be frustrated by that, even having a sense that this is somehow unjust. Surely our faith should exclude us from the wilderness experience. Surely if we’re just good enough, faithful enough, holy enough, we shouldn’t have to face suffering or danger or challenge.

But life with Christ cannot be reduced to “protection from danger” nor is faithfulness to God a religion of guaranteed happy ending (at least, certainly not in this life). Rather, if we look at the bible as a whole – the story of the people of Israel, the ministry of Jesus, and the life of the early church – we see the co-existence of danger and promise. We see wilderness: the wide open space of possibility and the desolate place of pain and darkness. And there, the people are continually brought back to relationship with God.

Joseph goes into the pit and then the hands of slave-traders: danger. He goes with a gift of interpretation and dreams of his future status: promise. Peter steps out into the storm: danger. Jesus is there on the water with him: promise. God is in the wilderness too, calling us to relationship, and asking us to trust.

At the start of our gospel passage, Jesus shows us something of how we can handle the Badlands. Matthew 14.23: “he went up the mountain by himself to pray. When evening came, he was there alone”. I find that the wilds usually force us to slow down: they’re like quicksand or a good Scottish peat bog. There’s no rushing to the other side. If you push, you sink further. But, if we give time to contemplation and prayer. And if we accept, welcome even, the opportunity to slow down, then we might find that we are indeed walking with God and learning that in danger and promise, there is love.

I wonder what that looks like for each of us? What does it look like to slow down? To meet God in the in the desert, or on the waves, of the wilderness?

And how might doing so transform our relationship with God and change the way that we share God’s love in the world?

Open your merciful ears, O Lord,

to the prayers of your humble servants:

and, that you would graciously grant what we ask,

make us desire what is pleasing in your sight;

through Jesus Christ, our Lord, who lives and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

God, world without end. Amen.

“Let anyone with ears listen!” This Sunday as you prepare for worship, you may wish to read through the gospel passage for today Matthew chapter 13 verses 1-9 and 18-23. Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” This Sunday as you prepare for worship, you may wish to read through the gospel passage for today Matthew chapter 13 verses 1-9 and 18-23. Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Although this is a very well-known parable, we can always find new insights into what it is saying to us as we read it through then listen for God’s word.

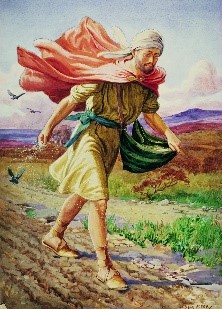

Today we hear about a farmer who goes out to sow seed. Nothing surprising in that, farmers sow seed all the time. Anyone who knows anything at all about what a plant needs to grow, won’t be surprised to hear that seed cast in the middle of a road, or on the rocks, or amongst thorns, doesn’t grow. However, there is something else so surprising that it should make us sit up and recognise the work of God’s spirit among us and in our world. We know it’s no surprise that the seed in this story, which was cast onto the road, into the rocks and amongst thorns didn’t grow. What is surprising is that the farmer chose to sow it in these places. This isn’t a rich man we are talking about, this is a poor tenant farmer who can only make a living for himself and his family if he not only makes wise choices about where to sow the seed, but also is blessed with good weather and a great deal of luck. Good seed was hard to come by and the wise farmer would make sure that his precious grain goes into the best possible soil. However, the farmer in our parable this morning tosses seed about while standing in the closest thing he can find to a car park at Tesco, where the pigeons will eat it if hundreds of feet and car tires don’t grind it into the ground first. In short, this farmer behaves as though this most precious seed was available in unlimited supply. What on earth is he thinking.

So now comes the real eye-opener, the second surprise in this parable. God blesses the farmer beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Normally a wise farmer who reaps a twofold harvest would be considered fortunate. A fivefold harvest would be a cause for celebration throughout the village and would be attributable only to the fulness of God’s rich blessing. But this foolish farmer who, in a world of scarcity as it was at that time, casts his seed on soil everyone knows is worthless and is blessed by God with an amazingly abundant harvest. God promises him a harvest of thirty, sixty, and a hundred times what he sowed. “Let anyone with ears listen!”

In this parable of the Sower and the seed, what we must remember is that the Kingdom of God was Jesus’ main emphasis in his ministry. It follows on from chapter twelve where Jesus finally broke away from the synagogue. The passage begins, “That same day Jesus went out of the house and sat beside the lake.” Matthews statement that Jesus went out of the house, actually points to the breaking away of Jesus from the synagogue in chapter twelve. He had ‘left the house’ so to speak because of disagreements with the religious leaders there. The crowd, mentioned in the next verse, represents those who were as yet uncommitted to any denomination or religion and who gathered to hear what Jesus had to say. And so, when Jesus began to speak about the Kingdom of God in his usual illusive way, it was hard to define exactly what the Kingdom was. Even his disciples were baffled and needed an explanation, which is why Jesus told the parable of the Sower and the seed.

We all know the story well, the Sower is God, the seed is the Kingdom and the various types of soil represents us, you and me. When we look at this story, it doesn’t sound as though God is a very frugal farmer. After all, most of the seed never takes root. But this is not really a story about the Sower and the seed, it’s a story about the different types of soil, or to put it another way, the different responses of the people to the message of Jesus about God’s Kingdom. The question for us to ponder is, what is the state of our hearts when the seeds are sown in us?

As we think about that, let’s examine the various conditions of the heart mentioned in this story. The hardened heart: These are the people who listen to the Word of God, but who are so caught up in their own lives, that they have no time to let the words sink in. They think they know best, and no one can tell them any differently, so they close their ears and their hearts.

The distracted heart: These people seem quite keen at the beginning to hear the Word and might even seem to be very excited about it. Then something else enters their lives and they forget the Word. They get caught up in whatever is the latest fad or attraction, and all their attention goes on this.

The defeated heart: People with defeated hearts are those who never really get the chance to listen to the Word. As soon as the Word is spoken, they have someone else whispering in their ear and telling them not to listen. They are easily defeated by others stronger willed than they are and who set out to lead them away from the Word.

And finally, the heart which I hope everyone here today has, The Hopeful heart: This is a heart that is filled with joy every time it listens to the Word of God. People who have hopeful hearts receive the Word of God through reading and listening to scripture. They are people who see the glass as being half full and not half empty. Those who accept the Word of God and hold to it firmly in spite of hardships or distractions, produce abundantly the ‘fruit’ of the Kingdom – that is to say, God’s will is fulfilled in their lives. We all have ears to listen, but do we always listen with joy and hold onto the Word so that we might spread the good news of God’s abundant Kingdom?

In our Gospel passage this morning, Jesus is not only talking about the Kingdom of God and how it is received, but about the growth of that Kingdom. So what is the message we need to hear from a story that suggests that God is like a farmer who tosses seed into car parks for the pigeons to eat, and in the surprising harvest that grows? I think that it says to us that Isaiah’s prophetic word, in our first reading this morning, is coming true. (You may wish to read Isaiah chapter 55 verse 1-2 and 10-13). In the first two verses of chapter 55 (which for some reason are not included in the lectionary), Isaiah says, “Ho, everyone who thirsts, come to the waters; and you that have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk without money and without price. Why do you spend your money for that which is not bread, and your labour for that which does not satisfy?” ‘Ho,’ in other words, Listen!

What we should realise is that the Kingdom of God has come among us, and we are encouraged to share it with everyone, regardless of who or what they are. Even seed that is sown on what is regarded as worthless ground is not worthless to God. He can and will bless the seed that is sown in everyone’s hearts and will encourage a response to come forth. God has blessed us richly, and God’s people, you and I, have been entrusted with the seed of God’s Word which is the most precious in the world. Ironically, these priceless commodities only gain value – the seed of God’s Word only bears fruit – when God’s people scatter it absolutely heedless of who they think is worthy to receive it. “Let anyone with ears listen!” Amen.

Some reflections for prayer:

Thank God for his abundant blessings in our lives.

Ask God to give us courage to spread the good news of his Kingdom to all we meet.

Pray for God’s harvest to be shared equally among all in every part of our world.

Pray for ‘fertile soil’ to receive the Word of God and to respond to it.

And may God bless you abundantly this coming week.

Moira

This week we mark  Sanctuary Sunday, the day when churches across Scotland, and worldwide, offer their prayers and express their solidarity with displaced people around the world, of whom there are more now than there have ever been before in history. Supporting and caring for refugees is something we’re always passionate about here at St Mary’s so today we join with others in particularly remembering God’s loving concern for the stranger, the alien, the sojourner, and the refugee. Sanctuary Sunday, the day when churches across Scotland, and worldwide, offer their prayers and express their solidarity with displaced people around the world, of whom there are more now than there have ever been before in history. Supporting and caring for refugees is something we’re always passionate about here at St Mary’s so today we join with others in particularly remembering God’s loving concern for the stranger, the alien, the sojourner, and the refugee.

Rachael writes: The story of Hagar (Genesis 21.8-21) is a powerful one to read on Sanctuary Sunday. As a woman who has been forced to leave her home multiple time (see Genesis 16), her story reflects the experiences of many refugees and asylum seekers. Her situation is desperate, and she has been failed by the people around her – the very people we usually consider heroes of the faith. She is dehumanised when Sarah refers to her only as “this slave woman”. Like so many people who are seeking sanctuary she is marginalised, demonised, and criminalised, rather than being treated as equally worthy of respect and dignity.

Tatiana from Odessa in Ukraine compares her own experience of fleeing her home with Hagar’s in these words:

“…you have a long road ahead through this parched land. There is nothing suitable to shelter you from the heat, there is not a single source of water along the road, only what you have taken with you. You are alone; it’s just you and the boy – the son you are responsible for. There is not a single other person around who could help you if necessary. And you wander in a direction unknown to you, no destination, not knowing where to turn, just wandering, hoping for safety. The situation is dire. What could be worse than this? Many Ukrainians have found themselves in this situation during the war. You’re running from danger, but don’t know where to go. In your hand is one suitcase, which now holds all your life’s belongings. And sometimes you don’t even have a suitcase – I did not have time to collect mine. In your hands are the hands of your children. Who will help? Where to run to? Where can you expect help? Everything around is new and unfamiliar. There are people around, but it is as if you are in a desert. Only you and your problems and no-one who could help!”*

At St Mary’s we have been working to find ways that we can help. We have a long standing relationship with Forth Valley Welcome who’s clothes hub for refugees we are now hosting in the church room. We also worked with them to put on a ceilidh for those staying at the Hydro and we collect toiletries that are distributed to those in need.

We support Castlemilk Community Church’s work with the refugees and asylum seekers who live in their area. The rectory garage is regularly packed to the rafters with donations of equipment and clothes for children and families from people all across Dunblane that are distributed weekly to those who need them in Castlemilk. And the Link group is building relationships with people in Castlemilk by hosting family days out in Dunblane. There we see a beautiful exchange of cultures as those who come often bring specialty dishes to share or delight everyone with a song from their homeland.

When God went into the desert to rescue Hagar the first time, she declared God’s name to be “El-roi” – “the God who sees me”. And in our gospel passage today (Matthew 10.24-39), Jesus tells us that a sparrow cannot fall from the sky without God’s knowledge; that even the hairs on our heads are counted. Tatiana from Ukraine writes “God truly sees and understands Hagar, and her worries and pain. God saves and restores her and promises a hopeful future. This is the God who sees you too…This is my God who gives hope, and gives life!”. All those who are forced to flee their homes, all 108.4 million people worldwide, are seen and known and loved by God. And no matter where they come from, how they travel, or where they are going, they deserve to be treated with the dignity and respect that God inherently created them with. All of St Mary’s interactions with people who are refugees or seeking asylum are based in this belief and why our interpersonal relationships are so important. By meeting them on a human level, we see not just number but people who are more than their immigration status; they are individuals with stories, creativity, and gifts to share. As much as we might hope to enrich their lives, we know that our relationships with them have greatly enriched our lives and our fellowship. We are learning to see our friends not as “other” but as fellow sojourners along the way, seeking new and abundant life.

Jesus also reminds us that the truth can be divisive and uncomfortable. Not everyone will like this message of love and care. We might have to step into some difficult places as we have conversations with friends and family, or lobby our MPs and MSPs, or even make changes in our own lives to be able to give in prayer, or financially, or to allow space for relationships with those seeking sanctuary here in Scotland.

When the world had discarded Hagar, God did not. God’s compassion is unfailing, especially for those who are suffering and going through a time of wilderness. We give thanks for those St Mary’s is journeying with and we say, “Yes God, we see what you see!”.

* extract from reflection by Tatiana Bondarenko in Scottish Faiths Action for Refugees, The God Who Sees Me: Worship Resources for Sanctuary Sunday 2023 sfar.org.uk

Posted by Revd Rachael Wright on 8th June 2023 The Living with Loss group at St Mary’s invites you to a drop in session in the Meeting Room of our Hall on Saturday 8th July from 2pm until 3.30 pm.

Come and have a cup of tea and a piece of cake with us, meet some of our team and find out what we can offer to help you. Everyone is welcome and you can bring a family member or a friend with you.

Get in touch with us if you would like to talk to someone or require further information.

Posted by Revd Rachael Wright on 30th April 2023  photo by Claire Jeannerat In recent times, the farmers of Great Britain have had a lot of bad press. Many would have us believe that British farms are, in the majority, characterised by huge, faceless, production line style agriculture. However, many farmers are still carrying on their craft in the traditional way, not so far removed from the farmers and shepherds in Jesus’ time.

Like those in first century Palestine, I know of a number of shepherds and shepherdesses who live at close proximity with their flock at certain times of the year. For one it’s important that she’s in her caravan in the fields during lambing time, so that she can be on hand to help twenty-four seven. For another, during the summer months when they are on the mountain plateaus, he lives in his shepherd’s hut on the hillside to keep a close watch. That same shepherd leads his 300 or so sheep on a 40 mile trek every year to reach the summer pastures, not pushing and harassing from the back but leading from the front with the sheep following the one whom they know and trust.

These types of farmers know their sheep. They know their lineage, their genetics and their issue, through generations. They know those who are prone to ailments or difficult births, where they’re hefted, who are the escape artists, the risk-takers, and the slowcoaches.

They too, despite what some sections of the media would have us believe, want their livestock to have an abundant life.

Jesus describes himself here as the gate who allows the shepherd and the sheep to come and go. A few verses on, he’ll say that he is shepherd, whom he has said “calls the sheep by name and leads them out”, “goes ahead of them”, and who “they follow because they know his voice”.

The sheep know the shepherd, they listen to the shepherd, and they follow the shepherd.

I would suggest that that is vocation. To know, listen to, and follow God.

Our realisation of our vocation relies on our knowing God. Knowing God’s loving character, compassionate nature, desire for justice and the redemption of all things. It also relies on knowing who we are in God – what character and desires God has created within us. And both of these are active knowing’s: they involve effort, energy, the giving of time and attention. Vocation relies on knowing God.

The next part of vocation is listening. We do a lot of listening not with our ears. Relying on video and telephone calls through the pandemic made us really aware of how much we rely on our other senses to interpret and understand people in conversation. We rely on our eyes, our sense of touch, and our intuition, when we converse with other people. Which is good because I have never audibly heard the voice of God! But I do know that by watching the world around me, listening to and weighing what is said by others, along with reading the Bible, and even sitting in the silence of prayer, somehow, I hear God. I hear God in those nudges to the conscience, those convictions of the heart, those fleeting thoughts that come as if from nowhere. God is speaking all the time, and the sheep are those who listen.

And finally: following. When you know God and who you are in him; when you’ve listened and heard the promptings and suggestions; the only option left is to follow. Sometimes that’s a tiny step, sometimes it’s a giant leap. In either case, you know that you are stepping into the loving arms of a Good Shepherd, of the one who came that we may have life and have it abundantly.

Vocations come in all shapes and sizes. Really the possibilities are endless. In the church they can look like a calling to licensed or ordained ministry, to lending your expertise on a board or committee at provincial and diocesan level, to being part of the stewards, coffee, or intercessions rotas. Buildings and gardens need management and tending, outreach initiatives need instigators and sustainers, children and young people need mentors and guides, everything needs people of prayer to underpin and gird it. We all have vocations to things outside of church too: to our families or our neighbourhoods; to jobs or voluntary roles; to a particular way of running a business. Vocations can change, stop, and start anew. You can have more than one!

Whatever it may be: know God and who God says you are. Listen, actively and intentionally. If God is speaking, it’s time to follow. Living in step with God like this is the way to abundant life.

Christ is the gate who opens the way.

God is the good shepherd who calls us by name.

And the Lord is our Shepherd. We shall not want. He makes us lie down in green pastures. He leads us beside still waters. He restores our soul. He leads us in right paths for his namesake. And even though we walk through the darkest valleys we need fear no evil. For God is with us to comfort and anoint. To offer the way to life that is abundant.

Peter writes

At the Baptism of Christ, back in January, Nerys encouraged us to spend the time between then and Pentecost to reflect on the significance of baptism. For Jesus, his baptism was in the Epiphany season and marked the beginning of his earthly ministry. In the Early Church though, baptisms almost always happened at Easter and we still renew our baptism promises in our Easter liturgy. It doesn’t happen often but if there is a baptism as well, it adds a lot to the joy of our Easter celebration. I still remember the thrill of baptising my twin grandsons on Easter Day twenty years ago.

They were still babes in arms but you can be baptised at any age. I remember in one parish how a man in his 80s asked me one day if he could be baptised. Apparently he had missed out because his father was away in the trenches in the First World War. I realised that this was something he had to do while he still could – and indeed he died a few months later.

This brought home to me that baptism is not just a happy family occasion. It is a serious business and in the Early Church the season of Lent was a period of intense preparation by prayer and fasting, and baptism was by full immersion. If you are ever in Milan, go and see the archaeological remains underneath the present cathedral. There is a massive font, 3 or 4 metres across. This is where St Ambrose would have baptised converts, including – staggering thought – St Augustine himself.

My colleague in Vevey, on Lake Geneva, often used to baptise people in the lake. I have to admit that when I was Rector in Largs I was never tempted to do it in in the Firth of Clyde but whether it’s your whole body or a splash of water on the head, it shows that baptism is part of the Easter mystery. Just as we once lived in liquid in our mother’s womb but then at the moment of birth gasp in the air, so at baptism we go down into the water, in which we can no longer live, and then we are lifted up, coughing and spluttering to breathe in the air. We leave the old life behind and breathe in the clear, pure air of new life. The meaning of baptism is to show us how we can can go down to the tomb but then be raised, reborn to a new, eternal life. We are shown that Jesus’ story of resurrection can be out story too – in this world as well as in the world to come.

Just as Jesus’ baptism marked the beginning of his earthly ministry, so our baptism – whether we remember it or not – is a sign that we have a ministry to fulfil. On Maundy Thursday the bishop blessed oil to be used at baptism. It is called the oil of chrism (or anointing). In ancient times people were anointed with oil was a sign that they were marked out for a special task and when Charles is crowned he will be anointed with oil blessed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. We also are called to serve God and our fellow men and women in the daily round, the common task. When we do, we have left the old life behind and have entered on a new life, the Easter life of resurrection.

For prayer and reflection.

Take some time to consider how we might fulfil our commitment to Christian life:

Will you continue in the Apostles’ teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread and in the prayers?

Will you proclaim the good news by word and deed, serving Christ in all people?

Will you work for justice and peace, honouring God in all creation?

Will you, with the whole Church, live and work for the kingdom of God?

The original font underneath Milan Cathedral

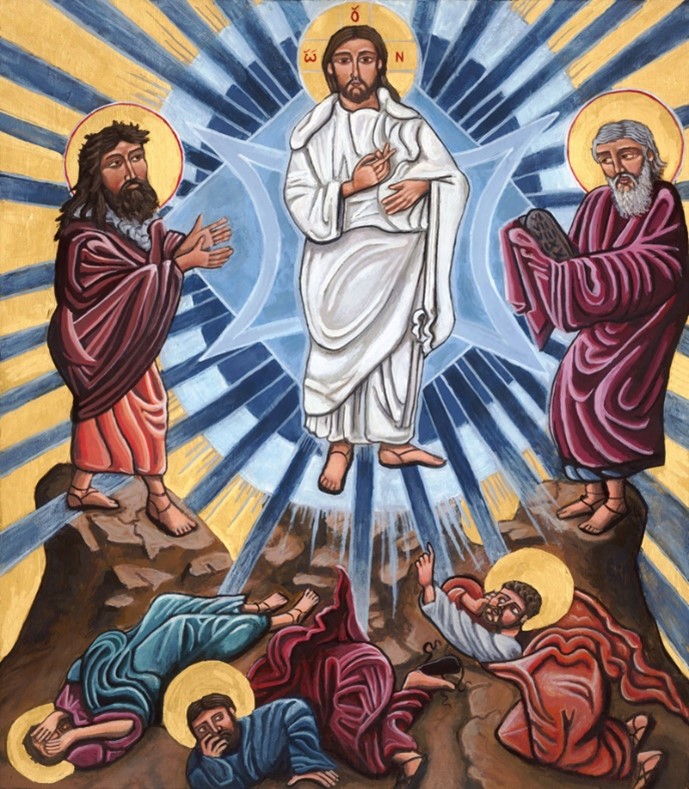

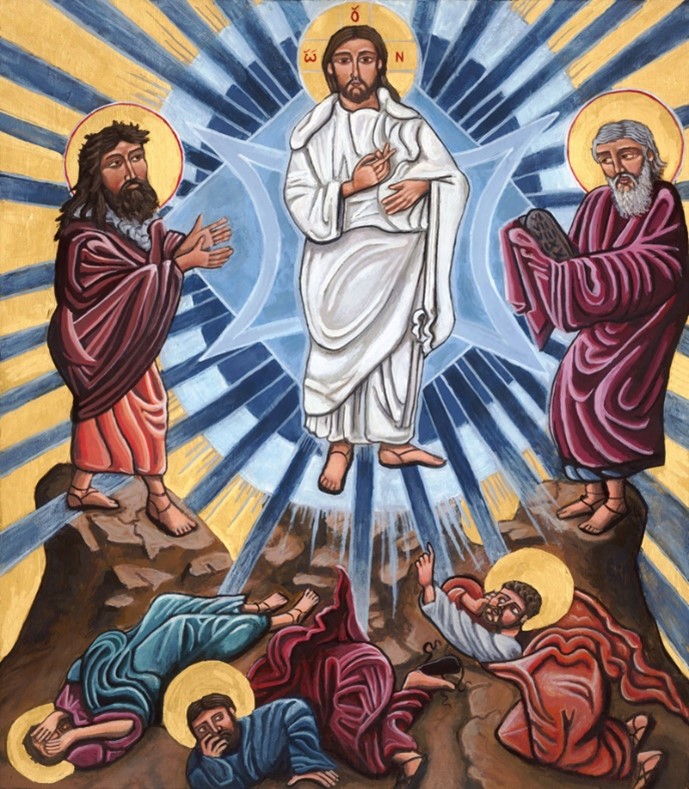

“God’s glory” is like a snapshot of God’s greatness and we get glimpses of that all the time – in something like a beautiful spring day but also in the kindness of other people and in finding it within ourselves to care for others. It’s not always easy to describe but I think we know it when we see it.

Take some time to read the passage and afterwards think about what Christ’s glory looks like in your mind as you read. How does it make you feel? What do you think your reaction would have been were you there? (You may wish to draw what you have seen, or to write down some words to describe it).

The disciples hid their faces when they saw Christ’s glory, they were so full of fear and wonder – we might use the word awe. They were in awe of Jesus as he revealed something of God.

We can see God’s glory in all kinds of ways and places. When we do, it’s important that we respond. One way that we do that in the Church is in baptism – in offering our children to be baptised when they’re little, or offering ourselves, and there committing to following Jesus. We also respond to God’s glory day by day and week by week, giving God praise and glory in our actions and words, in our worship, but also in how we treat other people and creation. God shows us God’s glory and then, in a way, we give it back. God shows us something amazing and special and full of life and hope, and we give God our amazement, we pray and we celebrate the eucharist, and we give God our lives and our hopes. We carry with us the song we sing every week, saying “Glory to God, glory to God!”, in everything we do. God shares with us something of God’s glory and then we offer it back. And in that other people can see God’s glory through us,

This is the last of our epiphany stories. But it doesn’t end at the disciples fear and wonder. Jesus says get up and do not be afraid before he goes back down the mountain and begins to prepare for his final journey to Jerusalem, where he will die and rise to life again. We also have a time of preparation ahead of is: Lent. It starts on Wednesday when we are marked with the sign of the cross in ash. From then on we don’t sing the Gloria, we have sombre purple hangings in church, and we quietly, reflectively prepare. It’s like walking with Jesus down off the mountain.

So as we head now towards Lent and our season of preparation for Easter, may we remember the many revelations of God’s glory that we have received. May we treasure them in our hearts, and may they sustain us as we sit in the trials and temptations of life at the bottom of the mountain. For there, as much as the peak, do we find Christ himself. There we walk with Jesus so that he can show us that God’s glory can be revealed through us, imperfect as we are.

Lord God, our creator, as we celebrate the revelation of your glory,

help us to turn ourselves to living a good Lent.

Help us to give up things that stand between us and your love,

and to walk with Jesus on the road that leads us closer to you.

We give up our Gloria only for a while,

so that we may make a more beautiful music in our hearts and lives

when we sing it again at Easter.

Amen.

Rachael writes: Jesus wasn’t baptised as a baby in the same way that many of us were. As was the law in Judaism, he was taken to the temple to be presented to God forty days after his birth. Mary and Joseph went with the offering designated for people who were poor, who couldn’t afford a whole lamb, but could take a pair of turtle doves or two young pigeons, to “redeem” Jesus having offered him like all first born males, human and animal had to be.

James B. Janknegt We see something of this presentation at the temple, this offering of Jesus to God for God’s work and will, in baptism today. Parents bring their children to church to present them to God, or adults present themselves. It’s a way of saying to God, “I want my child, or I choose for myself, to follow you God. To live your way and to share your love with the world”.

When they were there, Mary, Joseph, and Jesus, met a man called Simeon. He was full of the Holy Spirit, full of God, and God led him to the temple where he took the baby Jesus in his arms and declared Jesus to be “a light for revelation”. It doesn’t mean that Jesus glowed like a lightbulb but that he was revealing to the world the truth of who God is and what the world is like. He was showing the reality of our human situation and of God’s love and transformative work.

Anna also realised how important this baby was. She recognised that Jesus was going to change everything, that he was going to help her people to know God more, and make the world more like God intended. She was so in awe, so amazed, and so excited, that she couldn’t hold back.

I think most of us will be able to remember a time when we’ve been stuck in the darkness and desperate for just some light to show us the way. Maybe we woke up in the middle of the night and as our eyes adjust we realised that the light of the moon was peeping round the curtains just enough to light the way. Or perhaps it was more a darkness within us – a fear or anxiety – and it was the kind words of a friend, or the smile of a stranger that gave us hope in the midst of it. It doesn’t take much. Even a small, flickering candle flame can illuminate a great big space. When we’re in the presence of such a light, there’s no avoiding our being lit up by it too.

Mary and Joseph had come to offer Jesus to God but Simeon and Anna ended up offering themselves to Jesus. Their worlds were lit up by him as he banished the darkness for them, showing them the way and guiding them on. They were changed by their encounter with him and couldn’t help but tell everyone about it.

Jesus’ light has never gone out. It still shines brightly today drawing us in like it did for Simeon and Anna. And we offer ourselves to him, like they did, at baptism but also every day when we choose to follow him. We are illuminated by him and sent out into the world to shine. To shine with his truth and love and transformation.

That’s why we give people candles when they are baptised. To remind them that they carry Christ’s light with them into all the world. And at the end of our service in church today, we’ll remember that again as we light our candles and give thanks for Christ’s light in our lives. Then we’ll extinguish them and remember that the light of Christ is within us now and we go to share it with the world.

Mike Moyers, “Awake My Soul” When has Christ’s light illuminated your life? Where can you shine Christ’s light today?

I’d encourage you at home, if you’re safely able, to light a candle and offer these prayers:

Like Simeon, may I grow old in hope and wonder.

Like Anna, may I be in love with you all my days.

May I be open to truth, open to surprises.

May I let your spirit into my life.

May I let your justice change my behaviour.

May I live in the brightness of your joy.

Starmaker God, Lightner of the world,

bless us and warm us into the light of loving.

Bring us to the light of Jesus all the length and breadth of our nights and days.

As the candle, so my life:

flickering, burning, changing, alight and warm with the light which is you.

Amen. (by Ruth Burgess)

We remember the place of our new birth at baptism

Let us shine with the light of your love.

We turn from the crib to the cross.

Let us shine with the light of your love.

We go to carry his light.

Let us shine with the light of your love.

Thanks be to God.

Amen

Peter writes “Atishoo, atishoo, we all fall down” – This nursery rhyme probably dates back to the Great Plague of the 1660s, when sudden sneezing was considered the first symptoms of the disease and soon its victims would all fall down. And so, to this day, we still say “Bless you” when someone sneezes. But what do we mean when we say that? What did Jesus mean when he invoked the blessings that we call the Beatitudes?

Here, Jesus is following a form of Jewish prayers which is still used in synagogues and in homes today. Often they consist of blessings addressed to God, for instance before meals praising him for his goodness and generosity in providing for our needs. There are many similar prayers for other occasions. On getting dressed a pious Jew might say “Blessed is he who clothes the naked”.

We may also ask God to bless people or things, asking him to bestow his grace or show them his favour and protection, hence “Bless you” when we sneeze. At Epiphany, Rachel encouraged us to write an inscription above our front doors containing the letters CMB. These are the initials of the Three Wise Men (Caspar, Melchior, Balthazar) but they also stand for Christus mansionem benedicat – “May Christ bless this house”. That is, we are asking that his love and favour may dwell there and be felt by all who enter.

In asking God to bless things we are also expressing the intention that they are to be set aside for holy purposes. Before the Eucharistic Prayer, the priest may use a prayer to bless our offering of bread and wine and in the prayer itself we recall that Jesus blessed the bread and wine at the Last Supper. Similarly we ask God to bless the water in the font at baptism. In this way ordinary water becomes special, just as we come before him as ordinary people but made special through God’s blessing and called do some special task for him that only we can do. It may be a lifelong commitment or it may be a case of being in the right place at the right time. As St John Henry Newman wrote, we may never know in this life what that task is.

This brings me to the people that Jesus calls blessed in the Beatitudes. They come at the beginning of his earthly ministry and in a sense they set out his agenda. Those who are blessed are ordinary people, leading lives, full of God’s favour and protection, but who would not be considered blessed in the eyes of the world. What we need to look for, he says, is people’s character, finding contentment in simple things; longing for justice; indignant at the neglect of God’s will and not harbouring grudges or seeking revenge.

Blessedness is to be found in the topsy-turvy nature of the kingdom of heaven, where the first shall be last, the last first and where the judgements and attitudes of the world all fall down.

For prayer and meditation

“Praise God from whom all blessings flow. Praise him all creatures here below.” – To praise him is another way of blessing him. What other words come to mind when you think of blessing?

“Count your blessings”: – Spend a few moments to consider how you have been blessed in the past and are today. Thank God for them.

Look at the types of people Jesus calls blessed. Do any of them apply to you and what form did or does the blessing take? Do you need to work at any of them? Ask for help and guidance.

Who do you know who is in need of blessing today? Ask God to grant it to them.

Think of people whose lives and example have been a blessing to you or others. Give thanks for them.

Rachael writes: God calls in many different ways. It would be nice if they were all as straightforward as Jesus’ instruction to the disciples on the beach (Matthew 4.12-23). “Follow me” and off they go, apparently without question or hesitation. Thankfully there are plenty of other examples in the Bible of people to whom God gives a task and they try to deny that they’re up to it (Moses); make some terrible errors along the way (David); or are only convinced by some drastic measures (Paul). But how do you even know if you’re being called? We don’t have the luxury of Christ incarnate standing before us and speaking to us nor will many of us have been spoken to from a burning bush!

The miraculous can (and does) happen but we’re especially drawn to these stories of the fantastical, because we hope for such clarity and direction for ourselves. The idea that we all have an inherent purpose which we need to find is a big part of our culture now: even the tagline in the RAF’s TV advert at the moment is “Everyone’s got that one thing they were born to do”. I hope I wasn’t born to do just one thing. I hope I’m a more nuanced and complex creature than one which can be boiled down to a single skill or role. This idea of destiny reduces us down to the jobs that we do, meaning that life finishes when we retire and puts a lot of pressure on young people, which for most only leads to disappointment. I don’t think it’s how God intended things to be. All these people in the Bible were given specific tasks for a time but as part of a much bigger picture and story. If we’re going to understand our calling, we need to see that big picture.

It starts on the grandest scale, back in Genesis 1 when God calls all things into being. God speaks and there is light; God speaks and there is sky; God speaks and there is land, vegetation, planets, stars, animals, and eventually humans. God’s words summon these things from nothing – they are called into being and then called by name. In Genesis 2 God puts Adam in the garden to “work it and take care of it” (2.15). That is, to nurture it and to protect it, to help it reach its full potential and restrain the forces that would dismantle it back into chaos. This is the calling of humanity: the nurture and protection of the whole created order. Creation exists for the glory of God, and humanity within that for creation’s care and nurture.

If we zoom in just a little bit, we see that God chose to use a particular people to bless the rest of humanity. Israel was to be “a light for the nations” (Isaiah 49.6), remaining faithful to the true God in the face of the other nations’ idols and false worship. They were given laws full of justice and mercy. They were to shelter the stranger and care for the widowed and orphaned. Stories of heroics and miracles are easier for us to read than lists of laws and chapters of temple building instructions, but in focusing on individuals such as Moses, Elijah and David, we can forget that they were part of a much bigger story. We can lose sight of God’s calling of a nation to be a blessing to all humanity.

Then Christ comes and expands that calling to include the Gentiles as well as the Jews. The coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost births the Church, and a new people is called together, centered around Christ, to mediate to the whole world God’s self-giving love. They – we – are called, as a body, to represent to humanity the good news (ie. the “gospel” which Paul mentions in 1 Corinthians 1.10-18) that God has not given up on the world and continues to love and sustain it. Still fully a part of humanity, the Church is tasked with drawing people back into fellowship with God through Christ.

The baptismal liturgy of the Scottish Episcopal Church begins by saying that “In Christ God reaches out to us. In baptism God calls us to respond”. When we hear God’s call to follow, we offer ourselves in Baptism, another communal act – we can’t baptise ourselves. And at baptism we are called again: the liturgy asks for a profession of faith but also a commitment to Christian life. It asks if we will “continue in the Apostles’ teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread and in the prayers … proclaim the good news by word and deed, serving Christ in all people… work for justice and peace, honouring God in all Creation”.

Any other sense of calling, any other gifts and skills, all tasks and activities, are rooted and grounded in this identity: as a human being and as a baptised member of the Body of Christ. We can become frozen by a sense that we have to wait for the neon sign in the sky to tell us what to do but the reality is that we have already been told and it’s less about what we do and more about how we do it. There’s great freedom in that. Furthermore, it assures us that God never stops calling us into action and that what that looks like can change over time as we reach different stages in our lives.

So we are all called: as human beings, as baptised Christians, and as the Body of Christ the Church. We may discern in our circumstances, gifts, and desires, a calling to a particular task but our primary calling and identity will always be in the baptism in which we offered ourselves to God, and from which Christ sends his body the Church into the world.

Almighty God, by grace alone you call us and accept us in your service. Strengthen us by your Spirit, and make us worthy of your call; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

|

The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on.

The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on.

Orpheus is a young singer-songwriter, madly in love with Eurydice. They’re a penniless couple and as winter arrives, Orpheus’ fixation on his song writing leaves Eurydice hungry, tired, and desperate. She is found by Hades, the King of darkness and shadow, the King of the underworld, who convinces her to enter the underworld with him where she signs her life over to him. Immediately she begins to lose herself among the indentured masses of Hadestown. Orpheus of course realises what has happened and takes a very long road to the underworld. He finds her there, but Hades is reluctant to let her go eventually agreeing that they may leave on one condition: as they go along the dark, winding road, over the wall and back to the surface, Orpheus must walk in front while Eurydice walks behind him. And Orpheus must never look over his shoulder to check if she is there, or else she’ll return to Hadestown forever. In the musical Orpheus asks his mentor Hermes whether it is a trick. Hermes replies, ‘No, it’s a test’. They begin the long journey but over the singing of the masses of the underworld Orpheus cannot hear footsteps nor Eurydice’s voice. He has no idea whether she’s there. They persevere until just as Eurydice sings that she can see the light and this is almost all over, Orpheus loses his nerve and turns round. He sees Eurydice there with him and he knows that he has condemned her to an eternity in Hadestown.