Nerys writes, If I ever return to California, I would like to visit a church in San Francisco called St Gregory of Nyssa which has become well-known for a number of reasons. You may remember Bishop Ian speaking about its worship which features joyful singing and dancing by the whole congregation around the altar during the eucharist. It is also remarkable for its community work, especially for its ‘food pantry ministry’. Every Saturday, the church distributes fruit, vegetables and groceries to about 800 families in need in that part of San Francisco and with the encouragement and guidance of the team, these families are growing into supportive communities.

The inspiration for the food pantry came from a journalist called Sara Miles. She was brought up as an atheist. As an adult, she had no interest in becoming a Christian (or ‘a religious nut’ as she thought of it at the time). Then, early one Sunday morning in 1999, she wandered into St Gregory of Nyssa church and joined a service. At communion she received the bread and the wine and the experience transformed her life. She came to faith in Christ there and then and in the weeks and months that followed, she embraced the religion that she had previously scorned.

As she threw herself into the worship and community life of St Gregory of Nyssa church she discovered that Christianity isn’t all about the supernatural or good behaviour as she had been taught to believe. It’s about people – all kinds of people with real bodies and with real hunger, all longing to be fed spiritually, and some needing also to be fed with real food. Before long, the bread Sara Miles ate at that first communion had multiplied into tons and tons of groceries, piled up in the church, ready to be given away to people living in the poorest parts of the city. Under her leadership, the community of St Gregory of Nyssa set up a series of what we would call food banks whilst also seeking to draw attention to the scandal of hunger among working families who are not paid enough. In the book she later wrote about her experience which is called Take this bread, she says, ‘The mysterious sacrament turned out not to be a symbolic wafer but actual food – indeed the bread of life’.

I was reminded of this extraordinary story of coming to faith in Christ and putting that faith into action as I read today’s two passages from the pen of St Luke, Luke 24.36-48 and Acts 3.12-19. Just as it was the physical presence of the communion bread in her mouth that brought about the conversion of Sara Miles, it was the physical presence of Jesus in their midst that transformed his disciples. And, not only did they see him, hear his voice, and touch his body but he also invited them to eat with him.

Our translations read ‘he took a piece of broiled fish and ate it in their presence’, an act which I’ve always found rather strange. Where this unusual phrase happens again in Luke 13.26, it clearly means ‘to share a meal’. This interpretation seems to me more likely when we think of all the examples of table fellowship threading through this Gospel. Luke’s Jesus dines with tax collectors and other outcasts, with the Pharisees and other religious leaders, and of course, with his friends and disciples. So, understood in this way, the taking of the fish is not intended only as proof that he is not a ghost, but also as a reminder for his disciples of all the times when Jesus created community with them. It implies his acceptance of them despite their recent denial and desertion of him. It reminds them of the radical inclusion which he taught through his words and actions.

Eating the fish together with him may also have brought to their minds that first encounter on the shores of Lake Galilee when he called the fishermen to fish for people. And what about that time on the hillside when they witnessed five loaves and two broiled fish becoming a feast for thousands of hungry people? And, of course, that strange last meal in Jerusalem when he gave them the bread saying, ‘This is my body’ and the wine, saying, ‘This is my blood’.

The Lord’s Supper at Holy Trinity Church Pitlochry

As they eat together this last ‘Last Supper’, Jesus explains to them once more the significance of all that had happened in the previous three days. God had done something new and unexpected through him, and yet it was the same thing that God had always been doing in his dealings with his people Israel and the whole world. As they listen, they realise that all of Scripture points to the cross and the resurrection of Jesus. As they are reminded of the preaching of the prophets down the ages, they recall the words of John the Baptist and their own future roles start to become clear to them. Not only are they to testify to the risen Christ, but they are also to preach repentance and forgiveness of sins, as John did in words and as Jesus did through his actions also.

In our passage from the Book of Acts we see Peter doing exactly this in the precincts of the temple. He heals a man who was unable to walk and then uses the amazement of the onlookers as an opportunity to direct their attention to the life-changing power of faith in the risen Christ. They also can be set free and made whole by accepting the forgiveness now available to them through the death and resurrection of Jesus. This story has been included by Luke, not as an unusual or extraordinary event, but as a typical example of the apostles acting out what they were commanded by the risen Christ to do.

In today’s epistle, John also speaks as a witness – as someone who has experienced the presence of the risen Christ in his life – sharing with his readers what it is to be forgiven and to live as a beloved child of God. Today’s passage, 1 John 3.1-7, is a call to repentance, a call to become honest with God and ourselves. It is only then that we are able to see Christ as he is, in us and in those around us, and to seek to be as Christ-like as possible.

Following Christ is not easy, however, and not without cost as Luke demonstrates. It is to the hostile religious leaders of Jerusalem after a night in spent prison, that Peter’s next sermon is delivered. Preaching repentance and forgiveness of sins has consequences because it is not just a matter of encouraging individuals to change direction. It is about setting the whole world right – speaking truth to power, working for justice and lasting peace. We may feel powerless today in the face of the destruction of our planet and of such widespread violence, corruption and cruelty, but I believe that with every word and every non-violent action that witnesses to the risen Christ, the kingdom of God is coming into the world. We know that in areas of deep-set conflict, the only way towards reconciliation is repentance and forgiveness – the way of compassion that Jesus taught. It seems beyond belief, but that’s the point. When he was killed, it appeared to his followers that the powers of violence and death had silenced him for ever. But on the third day Jesus rose again, he came amongst them and commissioned them to be his voice, to continue his work. They responded with joy because they could see that he was alive and knew that somehow from now on he would always be with them. The risen Christ invites us also to join his community, to live always in his presence and to witness to him each in our own way in order to bring in God’s reign of peace on earth. I wonder what our response to this invitation is today?

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 12th April 2024 Are you looking for a new-to-you outfit for a night out, a cruise, a party or a wedding? Come to our Swishing Evening to pick up a bargain and support Start-up Stirling in the process.

Donations can be brought to St Mary’s any time before 10th May. Contact Nerys on rector@stmarysdunblane.org to make an arrangement.

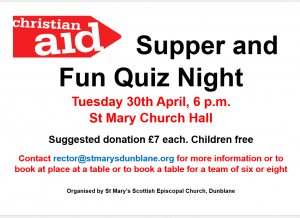

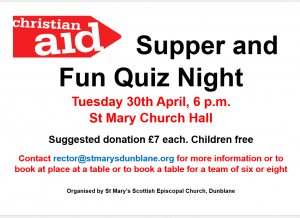

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 12th April 2024 You are welcome to join us for our fun and friendly quiz night. Book a place or book a table!

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 24th March 2024 The auction comes to an end on Easter Sunday. Please get your bids in before noon by emailing Nerys on nerysbrown@gmail.com.

All proceeds to a women’s empowerment project in the Diocese of Calcutta which offers young women training in business and dressmaking to lift them out of poverty.

Here are the items with reserved price or latest bid.

Charity McArdle cloudscape, 30x40cm oil on canvas, latest bid £100 Charity McArdle cloudscape, 30x40cm oil on canvas, latest bid £100

Ken Lochead, small framed watercolour of the Leighton Library 14″ x 12″ Latest bid £60 Ken Lochead, small framed watercolour of the Leighton Library 14″ x 12″ Latest bid £60

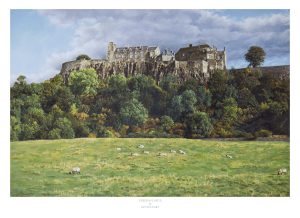

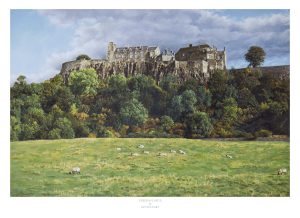

Kevin Leary, large framed limited edition print of Stirling Castle, 22″ x 26″ Reserve Price £30 Kevin Leary, large framed limited edition print of Stirling Castle, 22″ x 26″ Reserve Price £30

Ian McNab, small framed print of Stirling Castle 12″ x 14″ Reserve Price £20 Ian McNab, small framed print of Stirling Castle 12″ x 14″ Reserve Price £20

Mikey Davey, ‘Easter Cross’, oil on canvas, 28″ x 24″ Latest bid, £100 Mikey Davey, ‘Easter Cross’, oil on canvas, 28″ x 24″ Latest bid, £100

Book of Kells- style initial q, ink on paper, framed 21″ x 17 Latest bid £35 Book of Kells- style initial q, ink on paper, framed 21″ x 17 Latest bid £35

Louise Rayner framed print of ? Edinburgh 12″ x 18″ Latest bid £40 Louise Rayner framed print of ? Edinburgh 12″ x 18″ Latest bid £40

erve price £10

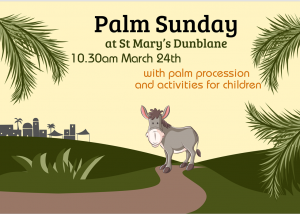

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 13th March 2024 Families with children are invited to join us in the hall for our Palm Sunday service, procession and activities.

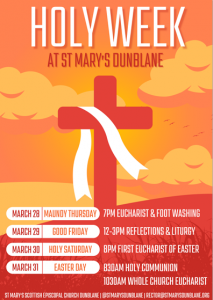

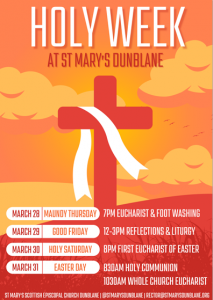

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 13th March 2024 Here are the services to be held at St Mary’s during Holy Week.

Nerys writes, Once, when one of my children was mentally unwell, I had a conversation with a wise consultant psychiatrist about stookies. ‘Mrs Brown’, he said, ‘The medication I’m giving your son will act like a plaster cast on a broken limb. It will protect his mind, enabling it to mend.’ Looking back at that difficult time when Davie and I often felt useless as parents, I realise that our role also was to act as stookies, supporting and protecting our child until he had recovered and had the strength to be independent of us again.

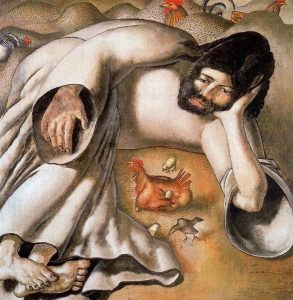

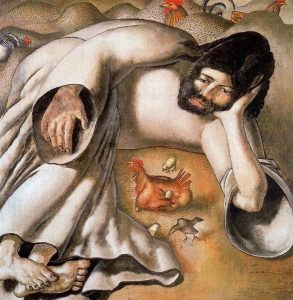

A plaster cast, just like scaffolding on a building, is a temporary measure. Once the house has been built, the scaffolding is removed and put away. In Stanley Spencer’s painting, ‘The Hen’ from his Christ in the Wilderness series, the mother hen guards her chicks by gathering them under her wings but a time will come when they will be able to fend for themselves. At that point, the mother hen will need to let them go.

In our Gospel reading for Mothering Sunday, Luke 2.33-35, we read of Mary being warned by wise and faithful Simeon of the cost of motherhood. After you’ve read it, I invite you to reflect on a hymn by Gillian Collins which traces Mary’s relationship with Jesus throughout her life.

Mary, joyful mother, resting from the birth,

do you sense the future for your Son on earth?

Angels, shepherds, wise men, all foretell a King,

but like every mother, you’ll know suffering.

Mary, anxious mother, searching for your boy,

Jesus does not mean to anger or annoy.

He’s still in the temple, asking questions deep.

This disturbing memory ponder now and keep.

Mary, hurt, excluded, standing in the cold,

Jesus inside preaching, challenging and bold,

seems now to belittle all your love so free.

Who will be my family? Those who follow me!

Mary, watching sadly by the cruel cross,

who can know your thoughts now, grieving in your loss?

Was it all for this, then? All your years of care?

He cries, “It is finished!” You weep with despair.

Mary, new disciple, in the upper room,

waiting, watching, praying – Spirit’s coming soon.

Mother of the Christ-child, suffering, faithful, true,

we have now a Saviour. God be praised for you!

For Mary, as for most human parents, there was a process of letting go of her child as he grew up. A time normally comes when the stookie or the scaffolding of practical parental care is removed and put away. But this isn’t true of God’s care which is eternal. In the painting which is based on Luke 13.34-35, Jesus’ is depicted as the embodiment of God’s desire to gather together the whole of creation. See how his body encircles the mother hen and her brood providing a protective refuge. Notice the expression on Jesus’ face. Do you see anxiety? Perhaps he is concerned for the other hens in the picture which are outside the circle of his protection. In the foreground, between his left arm and his feet, there is a way for them to enter. A little bird is coming to land. Look again and see that this is not a chick but a sparrow. There is room for everyone in the spacious, abundant love of God. Is there perhaps sadness also in Jesus’ face? Maybe he is contemplating the cost of this love.

You may wish to spend a moment with the painting, allowing it to speak to you of God’s unconditional love for you.

I find that Spencer’s paintings are like icons. The more you pray with them, the more you see. Another layer of meaning was revealed to me the other day. As I contemplated Christ’s body protecting the vulnerable mother hen and her chicks, it came to me that we are Christ’s body. This painting can be seen as an image of the church in action, providing a space where all God’s children can receive love and healing.

We are reminded in today’s epistle, the opening prayer of Paul’s second letter to the Christians at Corinth, 2 Corinthians 1.3-7, that ‘God comforts us in all our trouble so that we can then comfort people in every kind of trouble’. The word translated ‘comfort’ which is repeated so many times in this passage, is very rich in meaning according to Professor Tom Wright. It is, he writes, when ‘one person comes near another, speaking words which change their mood and situation, giving them courage, new hope, new direction, new insights which alter the way they face the rest of their life’. This is our calling here at St Mary’s, as part of Christ’s body in the world. Our purpose is to provide this kind of comfort to all we know within our community and to those we don’t know in the wider world. I invite you to take some time to pray for them now.

At church today there is an opportunity to make a donation to the Mothers’ Union Make a Mother’s Day Appeal. If you wish to give a gift which will help empower women and girls in developing countries to flourish, you can make a donation directly to the church’s bank account, marking your payment Make a Mother’s Day in the reference field. Our Bank Account details are Vestry of St Marys Episcopal Church, Sort code 831809, Account number 00279983

Moira writes

This morning as we continue our Lenten journey, we hear in our readings the essence of what our faith and belief is all about. In the lesson from the Old Testament, Exodus 20.1-17, we are reminded once again of the commandments that were given by God to keep his people walking in his ways. Psalm 19 speaks of the glory of God, his wisdom and the joy that comes from following in his ways. The Psalmist says, “The ordinances of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” So, by following his ordinances, or commandments, we remain faithful and true to God’s way. And in John 2.13-22 we hear about the disciple’s faith in what Jesus told them and how, “they believed the scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.”

I want to begin, however, with Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, 1.18-25. In this letter, Paul extols the grace of God, who saves his people from their foolishness as he tells them, “For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength.” Have you ever wondered why we, as Christians, wear a cross on a chain or on a badge and not, perhaps a stable manger as a symbol of our Christian faith? It is when you think about it, on the surface, a very dark and stark symbol. However, the cross on which Jesus died is the essence of our faith, a foolishness to those who are lost, as Paul tells us, and the power of God to those who are being saved. We cannot look forward to the hope and joy of the second coming of Jesus unless we first look back at the place of his death, where once and for all he gave his life for our redemption from sin! The most important words in this declaration are “where once and for all.” Jesus gave his life for our redemption from sin! Paul tells the Corinthians that we, the Christian church, preach Christ crucified, which is a stumbling block to the Jews and the Greeks. Christ is to the Christian community the power of God and also the wisdom of God. He asks them where are the wise, referring to the Greek philosophers whose works the Corinthians must have known well.

And what of the debater of the age that Paul speaks of? Could this remark have been directed at those who spouted rhetoric and conducted arguments in public about the meaning of language amongst other things? A bit like modern day orators on Twitter, or whatever it is now called! All of these people, in asserting worldly wisdom over God’s truth, are made foolish and purposeless in the face of the cross of Christ. I think that the point Paul is making is that any intellectual search for wisdom, for the understanding of human motives or behaviour, is doomed to failure, or at best to an orderly life of self-disciplined thinking. The human mind cannot by itself grasp, in its searching, the never-ending love of God which is revealed in the cross of Christ. In all of Paul’s epistles, it would seem that instead of applying human logic to all the problems that his readers seem to be going through, Paul used all of his trained and capable intellect to show how the gospel that he was proclaiming equated to human lives. In other words, Paul helped his readers to understand the wisdom of God and how it should show itself in their lives, transforming them in the way that they think and behave. People who have been transformed from unbelief into belief and who grow strong in their faith, have a strong connection to God through the love of Christ on the cross.

These are some of the things that we should be reflecting on during this season of Lent, asking ourselves, how close our connection is to God and how, being a Christian, has shaped us and moulded us as we grow in our faith and our belief.

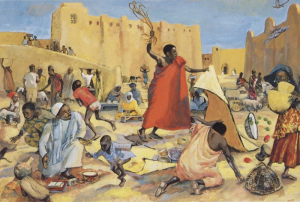

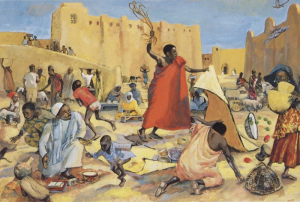

I’d like to move on now to our reading from the gospel of John. This is a passage which some people find very difficult to understand. Our image of Jesus as the gentle shepherd of his sheep is certainly put to the test in this passage as he storms into the temple and displays his anger. I don’t know about you, but I remember as a child, fighting or arguing with my brothers and stomping off, slamming doors and then facing the wrath of my mother. And so, I suppose, I should find this passage about the ‘cleansing of the temple’ quite reassuring. Here is Jesus, throwing things around in the ‘church’ of all places – the Jesus who was so calm and gentle the rest of the time. It makes me actually remember that he had human traits as well as being divine. John places this event early in Jesus’ ministry, instead of near its end, as the synoptic gospels do. There it becomes the act that helps to provoke his death. However, in John’s account, this movement to an earlier time in Jesus’ ministry means that the disciples are even more clueless than usual. They are new to Jesus, still trying to figure him out. They are still clinging to their ideas of who he is, rather than paying attention to what Jesus is saying about who he is.

Jesus Mafa Project Jesus Mafa Project

In this passage we see a new side to Jesus, someone who is so angered by what is going on in the temple grounds that he lashes out. It wasn’t so much that the temple authorities were selling animals for sacrifice, after all this is what people were coming to the temple to do, it was more that he could see that the authorities were being deceitful in what they were charging people. They were also rejecting some of the animals that people brought as having blemishes, so that people would have to buy from them. Another reason for Jesus’ anger was that people could only pay for the animals with temple coin. The money changers charged extortionate fees for exchanging Roman or Greek coins for temple coins, and of course the temple took its cut of the profits gained by the money changers. So it was not simply the presence of the money changers and the animals offered for sale that angered Jesus, after all, they were services meant for the convenience of people who had to travel long distances to get to Jerusalem. It was the misuse of authority in the blatant overcharging of even the poorest people that set Jesus off. People were stunned at the behaviour of Jesus, including the disciples who asked Jesus for an explanation. They couldn’t understand why Jesus said, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” It didn’t make sense to them, after all, the temple had been under re-construction for 46 years, how could Jesus raise it up in three days? As with so many things, the disciples only understood what Jesus had said later, in the light of the resurrection. We also know that the temple of which Jesus spoke was his body, not the bricks and mortar of the temple building! But there is another lesson to be learned from this reading, and that is the need for righteous anger, the righteous anger that Jesus displayed in the temple that day.

We need to have righteous anger in the face of injustice, extortion, and the exploitation of vulnerable people. Anger at such things is no bad thing, in fact it is a good cleansing thing. It is not the opposite of love. Anger at injustice is an appropriate expression of love and a cry for righteousness. Righteous anger is not a loss of control. Jesus is not out of control in this passage, he is very clear about the targets of his wrath. Righteous anger is about taking control, a move out of passive acceptance and towards change. Over the years we have seen change in the Scottish Episcopal Church. For decades now we have been working in our communities and beyond to bring change against racism, classism and poverty amongst others, and this can be seen in the Lenten appeals we support each year. We have also seen changes internally in the ordination of women and a fuller inclusion in the church of all people regardless of differing lifestyles, circumstances or backgrounds. And so, the challenge coming from our readings this morning, I think, is to remember that the wisdom and power of God is working in our lives, transforming us and moulding us into the people that God wants us to be. And as we are transformed, we should remember that we need that righteous anger to move us into action to help others however we can.

In your prayers this morning you may wish to pray for causes that are close to your heart:

• for people or countries facing injustice.

• for those who are struggling to feed their families.

• for those fleeing from oppression and abuse.

• and to ask God to grant you wisdom as you seek to follow in his way and to do his will.

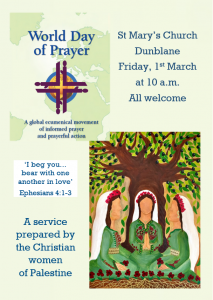

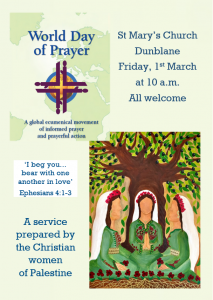

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 29th February 2024 Because of a beeping smoke alarm high in the rafters of St Mary’s which can’t be replaced until Saturday, the World Day of Prayer Service at 10 a.m. on Friday will now be held at St Blane’s Church.

Nerys writes: Have you ever ridden on the back of a bike that’s going too fast? That’s what it feels like to me sometimes when I read or listen to Mark’s Gospel. I want to shout, ‘Woah! Put the brakes on!’ In today’s Gospel passage, Mark 1.9-15, in just six sentences Mark has told the story of Jesus’ baptism in the river, his testing in the wilderness and the beginning of his ministry in the villages of Galilee. These important events whizz past and we’re on to the calling of the disciples and the stories of healing before we know it. So today, on the first Sunday of Lent, let’s put on the brakes and take some time to explore what Mark is telling us about Jesus and what we can learn from him.

So how does the passage begin? Here is the first sentence: In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan.

Mark doesn’t set the scene for us. Mark just gives us the bare facts. Let’s use our imagination to picture the crowds of excited people on the river bank. Can you see them flocking to John, that strange figure who had appeared in the wilderness? Can you hear his voice calling them to change their ways, to ask God to forgive all the things they’d done wrong, to come into the water to be baptised as a sign of a fresh start? Can you see Jesus queuing up with all these people? I wonder what moved him to respond to John’s call when he really didn’t need to be baptized at all?

Here’s the next sentence: And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him.

Mark zooms in of Jesus and what he sees as he is leaving the river. In Mark, these dramatic signs from God are just for him. The crowds are unaware of what’s happening to him. Their conversations carry on around him as the heavens are opened and he experiences an amazing vision of God who is about to do something new for the world.

This is something his people, the people of Israel, had been longing for down the generations. ‘O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the nations would tremble at your presence’ was the prayer of the prophet Isaiah (64.1). I wonder if this is when Jesus first catches a glimpse of God’s purpose for him. Is this the moment when he realises that he would be the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prayer?

Then out of heaven, God’s Spirit comes down like a gentle dove, not just upon him, but into him, filling him with power of God’s love. The same Spirit of God that moved over the face of the waters of the deep at the creation of the world. The same Spirit that would empower his followers at Pentecost and continues to empower us to this day.

Something else happens: And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.’

Later on in Mark, his disciples hear God speak these words about Jesus on the mountain top but just now they are for his ears only. I wonder how you imagine that voice saying those words? I wonder if you can imagine God whispering them to you right now? ‘You are my child. I love you and I delight in you.’

These words would have been familiar to Jesus. They are the words said by God in the Book of Isaiah about the Servant who is to suffer and die for the sins of the people (Isaiah 42.1-2): ‘Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations.’ I wonder if this is the moment when it becomes clear to Jesus that he is indeed God’s beloved Son, the healer humankind?

We’re left to guess what effect these words have of Jesus as Mark moves relentlessly on. And the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness.

Here Mark is at his most dramatic, using the most forceful of images. The Spirit immediately hurls Jesus into the wilderness. Ruach, the Hebrew word for God’s Spirit, can mean ‘breath’ but it can also mean ‘wind’ – a powerful, disruptive force.

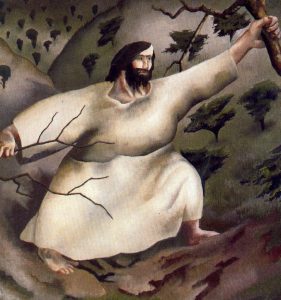

Stanley Spencer in the first of his famous series of paintings of Christ in the Wilderness, shows Jesus being propelled into the desert. See how he’s grabbing on to branches to steady himself as though he’s feeling a great force. Notice how his hair and cloak aren’t affected and the landscape remains still. This is an inner gale. This is God’s dynamic presence and power which continues to this day to push and pull, draw and drive God’s people here, there and everywhere, setting us on new pathways.

Mark has just one sentence on Jesus’ experience in the wilderness : He was in the wilderness for forty days, tempted by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angels waited on him.

Again, it is up to us to imagine the scene, to imagine those long days and nights in harsh, rocky surroundings as Jesus struggles with his thoughts and feelings. Mark doesn’t tell us the ways that Satan tests Jesus. We can only guess how the one who had opposed God’s people down the ages, seeks to deflect him from the path God has called him to. We aren’t given any details except that Jesus isn’t alone in the wilderness. Mark says that he is among the wild beasts and angels come to look after him.

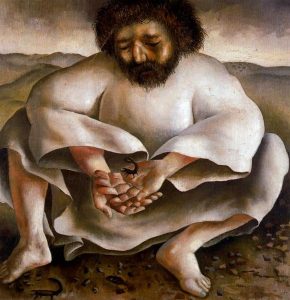

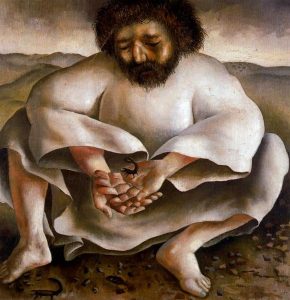

In the Judean desert. there would have been leopards, hyenas, vultures, venomous snakes and other dangerous creatures. Can you imagine sensing their presence in the darkness of night? Stanley Spencer depicts Jesus with all kinds of animals in his paintings. In one of them, we see him with a pair of scorpions, the most feared and deadly of the wild beasts of the desert. Instead of destroying them, Jesus cradles one in his hands and another one scuttles at his feet. I wonder how we respond to those things that strike fear in us?

God sends to Jesus angels to attend to his needs, just as God did to Elijah when he was at the end of his tether. They come to feed him, to encourage him, to comfort him, to bring him hope. Jesus is not expected to endure these trials on his own. God sends his servants to provide him with all he needs. I wonder if we have known angels in our lives who have supported and encouraged us in difficult times?

Mark, once more, says nothing about the effect these experiences had on Jesus. He simply tells us what happened next: Now after John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.

Jesus leaves the wilderness ready to begin his ministry. He is sure of who he is and what he is called by God to do. It is time for him to call others to turn to God and to trust in his message of God’s unconditional love.

I invite you to take a moment to bring to mind those times where you feel close to God, when you know that you are loved and blessed. Think of those times where there is testing and difficulty , when you feel threatened, anxious, afraid. Know that God is with you all the time and that God’s love is greater than any evil. Offer it all to God.

Join with me this week to pray for all people who are living in dangerous and difficult situations:

• for people in areas of the world where there is armed conflict,

• for those whose lives and livelihoods are affected by Climate Change,

• for refugees and asylum seekers around the world,

• for people who are in prison or homeless,

• for those in our community who are struggling financially,

• for those who are lonely,

• for those who are sick,

• for those grieving a loved one.

Loving God, during this Season of Lent show us by your Spirit how we can wait on those who need our support and prayers. Amen.

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 16th February 2024

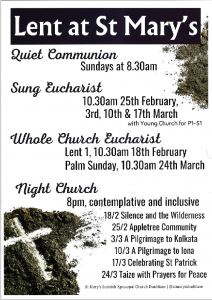

Something for everyone during the season of Lent …

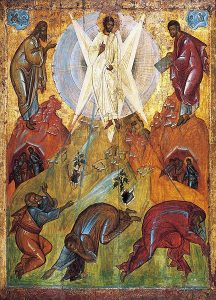

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, Peter writes, artists always paint the Transfiguration as their first icon. In fact, in the Orthodox Church they say the artist writes, not paints, the icon. That means it is created not just as a picture to be admired but to convey a message and to point to a meaning.

Icons and other religious art is not to be worshipped but to be honoured, venerated even, for the holy truth that it conveys. The Transfiguration scene calls out for visual presentation – with the three figures in a blaze of light on the mountain top and the disciples transfixed by the glory that shone around. At the centre is Jesus, his appearance transformed by this dazzling light. So what is this scene telling us?

15th century icon of the Transfiguration, unknown artist (public domain)

The light and the glory that shine forth are not reflected or have their source elsewhere. They come from within the person of Jesus himself. This is the uncreated light which signifies the divine nature of Jesus. But this divinity is present in a physical body, Jesus’ other nature, as a human being. It took the Early Church some 300 years to work this out and formulate it in the words of the Nicene Creed, which we repeat every Sunday: Jesus the Son of God and the second person of the Holy Trinity is two natures – human and divine – in one body.

Icons, and indeed most religious art, portray human bodies – of Jesus, his blessed Mother and indeed even God the Father himself. This is by no means idolatrous. We know perfectly well that God does not have hands but yet we happily sing “He’s got the whole world in his hands”. Like icons themselves, words like hands, eyes, arms are what our human language uses to help us get our heads round the reality that lies beneath and beyond.

The appearance of Jesus as a light-filled human body at the Transfiguration helps us to grasp the meaning of that phrase on the Book of Genesis, that God created us “in his image” and our bodies – and by extension our characteristics, personalities and capabilities all have the potential to illustrate or reveal the presence of God in our thoughts, actions and words. God has given us the gift of creativity, a sense of what is right or wrong, and a desire to work for the good of others. All this has huge implications for the way we treat our fellow humans, all of whom like us are made in his image. And, given that, to quote the First Letter of John “God is love and all who live in love live in God and God lives in them”, then it follows that the extent to which we love our fellow men and women, and indeed the whole of creation, must be the yardstick by which we measure the clarity, the brightness and the sharpness of the divine image in us.

As we come to God in prayer, in this coming season of Lent, examine ourselves and call to mind what we have done or failed to do, then we need to ask ourselves, “Have others seen God’s image in me? Do they see the light of his presence in my thoughts, words and deeds?”

And having examined ourselves, pray that we may embody that wonderful truth “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth”.

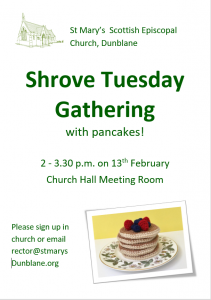

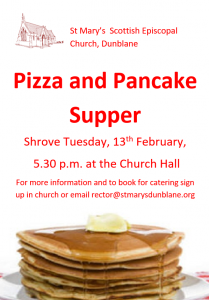

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 28th January 2024 Everyone is invited to our Shrove Tuesday events. Please get in touch on rector @stmarys.org or sign up at the back of church if you would like to attend.

Posted by Revd Nerys Brown on 28th January 2024 A Happy New Year to you all! Since this is the first magazine of 2024, I assume that it is not too late to use this greeting. I hope that it is not too late either to encourage you to make one more New Year’s resolution and to join me in seeking to try new things this year. I read an article recently claiming that trying new things can transform our lives for the better. It can help us discover our strengths and weaknesses, overcome our fears, build our confidence, boost our creativity and grow as people.

Here at St Mary’s we aim to offer a variety of Sunday services. If you have been attending the morning services regularly for a number of years, the liturgy will be comfortingly familiar. We also seek to provide services that are different and new, particularly at Night Church. We hope that these might teach us new ways of approaching prayer and worship and challenge us to think afresh about our faith and the way we live it out.

This month at Night Church, Ruth Burgess will lead us in a celebration of the ancient festival of Candlemas, Iain Goring, inspired by the author Richard Foster, will reflect on spiritual disciplines, and Kate Sainsbury will share with us a year in the life of the Appletree Community which she has founded to support her son Louis. This month also, we will mark the beginning of Lent with services in the morning and the evening of Ash Wednesday, 14th February. If you haven’t observed Lent before, what about coming to one of these or to the whole church service on the first Sunday of the season to find out more?

You are also invited to come together to mark Shrove Tuesday with pancake events in the church hall on the afternoon or evening of 13th February. These will be the first in a series of social events to which you are encouraged to invite relatives, friends or neighbours. Please consider who you might ask to come with you either to the afternoon gathering or to the supper – details below.

The Gospel we’ll be using in our eucharistic services during 2024 is the Gospel of Mark, the earliest and probably the most puzzling of the four Gospels. It is also the shortest, possibly designed to be read aloud in one sitting of a church community. Some of you have already agreed to meet this month to read the whole of this Gospel together. It is not too late to sign up for a morning, afternoon or evening session in the Rectory or in someone’s home. Hearing the Gospel in this new way can be a powerful experience. It may lead to further gatherings to look in detail at various aspects of Mark and explore its themes. We’ll have to wait and see!

At St Mary’s we also offer opportunities to meet regularly in groups during the week to discuss and pray together and get to know each other. If you would like to find out about the Monday Gathering, the Men’s Group, the Young Adults Group, the Prayer Group, Sensible Shoes and The Chosen, please get in touch with the organisers, some of whose contact details are at the back of the magazine, or with me. A new home group will soon be launched which will hopefully bring together Christians from different churches in Dunblane to pray and learn together and provide support for one another. This may be the new thing for you to try this year! If so, I urge you to come to the introductory meeting or failing that, to contact Martin or Jill Wisher to find out more.

Meeting to worship and to work for good causes along with members of other local churches has always been an important part of the life of St Mary’s. This year, it’s our turn to host the World Day of Prayer in Dunblane. If you haven’t attended this service before, what about coming along to join in the world-wide wave of prayer and to hear a powerful message from the Christian women of Palestine?

St Mary’s is also part of the Diocese of St Andrews, Dunkeld and Dunblane, a group of about 50 churches under the authority of Bishop Ian Paton. During the year there will be opportunities to meet with members of our sister churches for services and for other activities like the walks detailed below, organised by our Pilgrim Pastor, Duncan Weaver, along the Fife Pilgrim Way.

This month also, there will be a special Diocesan Evensong to welcome Bishop Marinez of Amazonia and celebrate our new link with her diocese in Brazil. This will be a great opportunity for some of you to visit our cathedral in Perth for the first time and to find out about what may turn out to be an exciting new project for our church.

In the meantime, please consider what other new things we could offer this year to build up our church community and strengthen our links with the wider world. I would be delighted to hear from you!

with love,

Nerys

Nerys writes: The repentant Jonah fresh from the belly of the whale, the psalmist beset by enemies, Paul, writing at a time of great pressure from imperial Rome, and Jesus, starting his ministry under the shadow of John’s arrest – in each of our readings today – Jonah 3.1-5, 10, Psalm 62.5-12, 1 Corinthians 7.29-31 and Mark 1.14-20 – we hear of a response to a call to God at a time of crisis.

It is often when we are in crisis that we turn to God, seeking God’s wisdom or guidance, comfort or strength. We trust that God will hear our calls of distress even when they come out of the blue, but will we recognise God’s voice when God responds to our plea? As the Vicar of Soham said in the wake of the murder of two schoolgirls in his parish many years ago now, when we’re drowning is not the best time to start learning to swim. Getting to know God’s voice takes practice. It is a lifetime’s work.

Our Gospel today is the first in a series of passages from the Gospel of Mark which will take us to the middle of Lent. I would like to encourage you to take time over the next few weeks to get to know God’s voice a little better by allowing God to speak to you through this Gospel.

Mark’s Gospel is a Gospel written at a time of crisis. Scholars think that it was produced either just after or just before AD 70, one of the most traumatic dates in the early history of the Jewish people. It was the year when Jerusalem was attacked and captured by the Roman army after a siege. Over a million people were killed and almost 100, 000 enslaved, the Temple was destroyed and the whole country laid waste. In its opening sentence, this work is described as an evangelion, a Greek word used for an important public announcement about a significant event which would change people’s lives for the better. It is a message of good news about someone called ‘Jesus Christ (Jesus the Messiah), the son of God’ . This was someone whose coming was prophesied by Isaiah and proclaimed by John the Baptist. This was someone who came to Galilee announcing a regime change. God’s kingdom is at hand. It is time to change the way we think and the way we live our lives.

The narrative forges ahead with breathless urgency and excitement. It is written in the style of the popular storyteller as a series of anecdotes vividly told, with short sentences strung together, the word ‘immediately’ appearing time and time again moving the action swiftly and jerkily along. This is not a Gospel to be read slowly, chewing on every morsel. In fact, it was probably intended to be listened to in single session.

When we read it like this, we can imagine the disconcerting and exhilarating impact this Gospel had on those who first heard it, and we can begin to understand what its author is seeking to do. For hundreds of years, Mark was felt by the Church to be inferior to the other three Gospels which are written in a more sophisticated style and present in more detail the teaching of Jesus. It was only in the nineteenth century that it was discovered that Mark wasn’t an abridged version of Matthew but the earliest surviving record of the life and teaching of Jesus. And it is only in the last hundred years that scholars have realised that it is not simple or naïve but ‘shot through with deeply theological perspectives’, to use the words of Rowan Williams.

It is when we read or listen to it from beginning to end that we notice, that although Mark is the shortest of the four Gospels it consistently provides much more detailed descriptions of events than Matthew and Luke. In the account of the feeding of the five thousand, for example, Mark tells us that the grass the people were sitting on was green. This little detail which indicates what time of year the miracle happened, not only makes the story more vivid but also according to some scholars, suggests that it is based on an eyewitness account of the event. The identity of Mark has been lost in the mists of time, but there is an ancient tradition that he was the secretary of St Peter. This was recorded early in the second century by a bishop who had learnt it from his churches in Asia Minor. According to this tradition, Mark not only wrote down but also interpreted what Peter had said to him, so that it would be accessible to new hearers and readers.

It is when we read the Gospel from beginning to end that we begin to see the great skill and artistry behind the presentation of this series of apparently simple stories. Threads of continuity come to light and we notice repeated behaviour in the three groups of characters who appear regularly in the story. The religious authorities – priests, scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees – are suspicious, sceptical and argumentative opposed to Jesus from the start. The crowd which appears more consistently in Mark than in the other Gospels, is impressed by his teaching and his miracles but its members never seem able to take a step beyond expressing wonder and amazement. The disciples follow Jesus but never really grasp who he is and what he had come to do. It is only the ragbag collection of people in crisis – like the man possessed by demons, the woman who is haemorrhaging blood, Jairus whose daughter had died, the Syrophoenician woman or the blind man from Bethsaida – who recognise him as the Christ, the Son of God, and call out to him for help. The way Mark portrays these characters doesn’t just draw us into the story but challenges us to respond ourselves to Jesus from amidst the crises of our lives and our times.

I urge you to sign up to meet with others in the congregation to hear Mark’s message of good news read in a single session, or failing that, to set aside an hour and a half sometime in the next few weeks to read it through yourself. Allow this ancient little book to work on you, to bring you closer to Jesus so that you will better recognise God’s voice.

An icon of St Mark written by Diana, late wife of Hugh Grant.

|

Charity McArdle cloudscape, 30x40cm oil on canvas, latest bid £100

Charity McArdle cloudscape, 30x40cm oil on canvas, latest bid £100 Ken Lochead, small framed watercolour of the Leighton Library 14″ x 12″ Latest bid £60

Ken Lochead, small framed watercolour of the Leighton Library 14″ x 12″ Latest bid £60

Kevin Leary, large framed limited edition print of Stirling Castle, 22″ x 26″ Reserve Price £30

Kevin Leary, large framed limited edition print of Stirling Castle, 22″ x 26″ Reserve Price £30

Ian McNab, small framed print of Stirling Castle 12″ x 14″ Reserve Price £20

Ian McNab, small framed print of Stirling Castle 12″ x 14″ Reserve Price £20 Mikey Davey, ‘Easter Cross’, oil on canvas, 28″ x 24″ Latest bid, £100

Mikey Davey, ‘Easter Cross’, oil on canvas, 28″ x 24″ Latest bid, £100 Book of Kells- style initial q, ink on paper, framed 21″ x 17 Latest bid £35

Book of Kells- style initial q, ink on paper, framed 21″ x 17 Latest bid £35

Louise Rayner framed print of ? Edinburgh 12″ x 18″ Latest bid £40

Louise Rayner framed print of ? Edinburgh 12″ x 18″ Latest bid £40

Jesus Mafa Project

Jesus Mafa Project