Nerys writes, If I ever return to California, I would like to visit a church in San Francisco called St Gregory of Nyssa which has become well-known for a number of reasons. You may remember Bishop Ian speaking about its worship which features joyful singing and dancing by the whole congregation around the altar during the eucharist. It is also remarkable for its community work, especially for its ‘food pantry ministry’. Every Saturday, the church distributes fruit, vegetables and groceries to about 800 families in need in that part of San Francisco and with the encouragement and guidance of the team, these families are growing into supportive communities.

The inspiration for the food pantry came from a journalist called Sara Miles. She was brought up as an atheist. As an adult, she had no interest in becoming a Christian (or ‘a religious nut’ as she thought of it at the time). Then, early one Sunday morning in 1999, she wandered into St Gregory of Nyssa church and joined a service. At communion she received the bread and the wine and the experience transformed her life. She came to faith in Christ there and then and in the weeks and months that followed, she embraced the religion that she had previously scorned.

As she threw herself into the worship and community life of St Gregory of Nyssa church she discovered that Christianity isn’t all about the supernatural or good behaviour as she had been taught to believe. It’s about people – all kinds of people with real bodies and with real hunger, all longing to be fed spiritually, and some needing also to be fed with real food. Before long, the bread Sara Miles ate at that first communion had multiplied into tons and tons of groceries, piled up in the church, ready to be given away to people living in the poorest parts of the city. Under her leadership, the community of St Gregory of Nyssa set up a series of what we would call food banks whilst also seeking to draw attention to the scandal of hunger among working families who are not paid enough. In the book she later wrote about her experience which is called Take this bread, she says, ‘The mysterious sacrament turned out not to be a symbolic wafer but actual food – indeed the bread of life’.

I was reminded of this extraordinary story of coming to faith in Christ and putting that faith into action as I read today’s two passages from the pen of St Luke, Luke 24.36-48 and Acts 3.12-19. Just as it was the physical presence of the communion bread in her mouth that brought about the conversion of Sara Miles, it was the physical presence of Jesus in their midst that transformed his disciples. And, not only did they see him, hear his voice, and touch his body but he also invited them to eat with him.

Our translations read ‘he took a piece of broiled fish and ate it in their presence’, an act which I’ve always found rather strange. Where this unusual phrase happens again in Luke 13.26, it clearly means ‘to share a meal’. This interpretation seems to me more likely when we think of all the examples of table fellowship threading through this Gospel. Luke’s Jesus dines with tax collectors and other outcasts, with the Pharisees and other religious leaders, and of course, with his friends and disciples. So, understood in this way, the taking of the fish is not intended only as proof that he is not a ghost, but also as a reminder for his disciples of all the times when Jesus created community with them. It implies his acceptance of them despite their recent denial and desertion of him. It reminds them of the radical inclusion which he taught through his words and actions.

Eating the fish together with him may also have brought to their minds that first encounter on the shores of Lake Galilee when he called the fishermen to fish for people. And what about that time on the hillside when they witnessed five loaves and two broiled fish becoming a feast for thousands of hungry people? And, of course, that strange last meal in Jerusalem when he gave them the bread saying, ‘This is my body’ and the wine, saying, ‘This is my blood’.

The Lord’s Supper at Holy Trinity Church Pitlochry

As they eat together this last ‘Last Supper’, Jesus explains to them once more the significance of all that had happened in the previous three days. God had done something new and unexpected through him, and yet it was the same thing that God had always been doing in his dealings with his people Israel and the whole world. As they listen, they realise that all of Scripture points to the cross and the resurrection of Jesus. As they are reminded of the preaching of the prophets down the ages, they recall the words of John the Baptist and their own future roles start to become clear to them. Not only are they to testify to the risen Christ, but they are also to preach repentance and forgiveness of sins, as John did in words and as Jesus did through his actions also.

In our passage from the Book of Acts we see Peter doing exactly this in the precincts of the temple. He heals a man who was unable to walk and then uses the amazement of the onlookers as an opportunity to direct their attention to the life-changing power of faith in the risen Christ. They also can be set free and made whole by accepting the forgiveness now available to them through the death and resurrection of Jesus. This story has been included by Luke, not as an unusual or extraordinary event, but as a typical example of the apostles acting out what they were commanded by the risen Christ to do.

In today’s epistle, John also speaks as a witness – as someone who has experienced the presence of the risen Christ in his life – sharing with his readers what it is to be forgiven and to live as a beloved child of God. Today’s passage, 1 John 3.1-7, is a call to repentance, a call to become honest with God and ourselves. It is only then that we are able to see Christ as he is, in us and in those around us, and to seek to be as Christ-like as possible.

Following Christ is not easy, however, and not without cost as Luke demonstrates. It is to the hostile religious leaders of Jerusalem after a night in spent prison, that Peter’s next sermon is delivered. Preaching repentance and forgiveness of sins has consequences because it is not just a matter of encouraging individuals to change direction. It is about setting the whole world right – speaking truth to power, working for justice and lasting peace. We may feel powerless today in the face of the destruction of our planet and of such widespread violence, corruption and cruelty, but I believe that with every word and every non-violent action that witnesses to the risen Christ, the kingdom of God is coming into the world. We know that in areas of deep-set conflict, the only way towards reconciliation is repentance and forgiveness – the way of compassion that Jesus taught. It seems beyond belief, but that’s the point. When he was killed, it appeared to his followers that the powers of violence and death had silenced him for ever. But on the third day Jesus rose again, he came amongst them and commissioned them to be his voice, to continue his work. They responded with joy because they could see that he was alive and knew that somehow from now on he would always be with them. The risen Christ invites us also to join his community, to live always in his presence and to witness to him each in our own way in order to bring in God’s reign of peace on earth. I wonder what our response to this invitation is today?

Nerys writes, Once, when one of my children was mentally unwell, I had a conversation with a wise consultant psychiatrist about stookies. ‘Mrs Brown’, he said, ‘The medication I’m giving your son will act like a plaster cast on a broken limb. It will protect his mind, enabling it to mend.’ Looking back at that difficult time when Davie and I often felt useless as parents, I realise that our role also was to act as stookies, supporting and protecting our child until he had recovered and had the strength to be independent of us again.

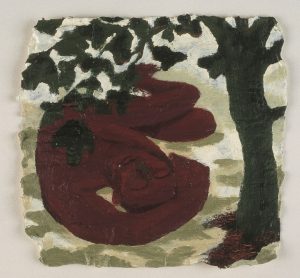

A plaster cast, just like scaffolding on a building, is a temporary measure. Once the house has been built, the scaffolding is removed and put away. In Stanley Spencer’s painting, ‘The Hen’ from his Christ in the Wilderness series, the mother hen guards her chicks by gathering them under her wings but a time will come when they will be able to fend for themselves. At that point, the mother hen will need to let them go.

In our Gospel reading for Mothering Sunday, Luke 2.33-35, we read of Mary being warned by wise and faithful Simeon of the cost of motherhood. After you’ve read it, I invite you to reflect on a hymn by Gillian Collins which traces Mary’s relationship with Jesus throughout her life.

Mary, joyful mother, resting from the birth,

do you sense the future for your Son on earth?

Angels, shepherds, wise men, all foretell a King,

but like every mother, you’ll know suffering.

Mary, anxious mother, searching for your boy,

Jesus does not mean to anger or annoy.

He’s still in the temple, asking questions deep.

This disturbing memory ponder now and keep.

Mary, hurt, excluded, standing in the cold,

Jesus inside preaching, challenging and bold,

seems now to belittle all your love so free.

Who will be my family? Those who follow me!

Mary, watching sadly by the cruel cross,

who can know your thoughts now, grieving in your loss?

Was it all for this, then? All your years of care?

He cries, “It is finished!” You weep with despair.

Mary, new disciple, in the upper room,

waiting, watching, praying – Spirit’s coming soon.

Mother of the Christ-child, suffering, faithful, true,

we have now a Saviour. God be praised for you!

For Mary, as for most human parents, there was a process of letting go of her child as he grew up. A time normally comes when the stookie or the scaffolding of practical parental care is removed and put away. But this isn’t true of God’s care which is eternal. In the painting which is based on Luke 13.34-35, Jesus’ is depicted as the embodiment of God’s desire to gather together the whole of creation. See how his body encircles the mother hen and her brood providing a protective refuge. Notice the expression on Jesus’ face. Do you see anxiety? Perhaps he is concerned for the other hens in the picture which are outside the circle of his protection. In the foreground, between his left arm and his feet, there is a way for them to enter. A little bird is coming to land. Look again and see that this is not a chick but a sparrow. There is room for everyone in the spacious, abundant love of God. Is there perhaps sadness also in Jesus’ face? Maybe he is contemplating the cost of this love.

You may wish to spend a moment with the painting, allowing it to speak to you of God’s unconditional love for you.

I find that Spencer’s paintings are like icons. The more you pray with them, the more you see. Another layer of meaning was revealed to me the other day. As I contemplated Christ’s body protecting the vulnerable mother hen and her chicks, it came to me that we are Christ’s body. This painting can be seen as an image of the church in action, providing a space where all God’s children can receive love and healing.

We are reminded in today’s epistle, the opening prayer of Paul’s second letter to the Christians at Corinth, 2 Corinthians 1.3-7, that ‘God comforts us in all our trouble so that we can then comfort people in every kind of trouble’. The word translated ‘comfort’ which is repeated so many times in this passage, is very rich in meaning according to Professor Tom Wright. It is, he writes, when ‘one person comes near another, speaking words which change their mood and situation, giving them courage, new hope, new direction, new insights which alter the way they face the rest of their life’. This is our calling here at St Mary’s, as part of Christ’s body in the world. Our purpose is to provide this kind of comfort to all we know within our community and to those we don’t know in the wider world. I invite you to take some time to pray for them now.

At church today there is an opportunity to make a donation to the Mothers’ Union Make a Mother’s Day Appeal. If you wish to give a gift which will help empower women and girls in developing countries to flourish, you can make a donation directly to the church’s bank account, marking your payment Make a Mother’s Day in the reference field. Our Bank Account details are Vestry of St Marys Episcopal Church, Sort code 831809, Account number 00279983

Moira writes

This morning as we continue our Lenten journey, we hear in our readings the essence of what our faith and belief is all about. In the lesson from the Old Testament, Exodus 20.1-17, we are reminded once again of the commandments that were given by God to keep his people walking in his ways. Psalm 19 speaks of the glory of God, his wisdom and the joy that comes from following in his ways. The Psalmist says, “The ordinances of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” So, by following his ordinances, or commandments, we remain faithful and true to God’s way. And in John 2.13-22 we hear about the disciple’s faith in what Jesus told them and how, “they believed the scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.”

I want to begin, however, with Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, 1.18-25. In this letter, Paul extols the grace of God, who saves his people from their foolishness as he tells them, “For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength.” Have you ever wondered why we, as Christians, wear a cross on a chain or on a badge and not, perhaps a stable manger as a symbol of our Christian faith? It is when you think about it, on the surface, a very dark and stark symbol. However, the cross on which Jesus died is the essence of our faith, a foolishness to those who are lost, as Paul tells us, and the power of God to those who are being saved. We cannot look forward to the hope and joy of the second coming of Jesus unless we first look back at the place of his death, where once and for all he gave his life for our redemption from sin! The most important words in this declaration are “where once and for all.” Jesus gave his life for our redemption from sin! Paul tells the Corinthians that we, the Christian church, preach Christ crucified, which is a stumbling block to the Jews and the Greeks. Christ is to the Christian community the power of God and also the wisdom of God. He asks them where are the wise, referring to the Greek philosophers whose works the Corinthians must have known well.

And what of the debater of the age that Paul speaks of? Could this remark have been directed at those who spouted rhetoric and conducted arguments in public about the meaning of language amongst other things? A bit like modern day orators on Twitter, or whatever it is now called! All of these people, in asserting worldly wisdom over God’s truth, are made foolish and purposeless in the face of the cross of Christ. I think that the point Paul is making is that any intellectual search for wisdom, for the understanding of human motives or behaviour, is doomed to failure, or at best to an orderly life of self-disciplined thinking. The human mind cannot by itself grasp, in its searching, the never-ending love of God which is revealed in the cross of Christ. In all of Paul’s epistles, it would seem that instead of applying human logic to all the problems that his readers seem to be going through, Paul used all of his trained and capable intellect to show how the gospel that he was proclaiming equated to human lives. In other words, Paul helped his readers to understand the wisdom of God and how it should show itself in their lives, transforming them in the way that they think and behave. People who have been transformed from unbelief into belief and who grow strong in their faith, have a strong connection to God through the love of Christ on the cross.

These are some of the things that we should be reflecting on during this season of Lent, asking ourselves, how close our connection is to God and how, being a Christian, has shaped us and moulded us as we grow in our faith and our belief.

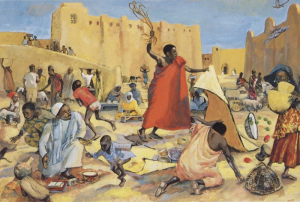

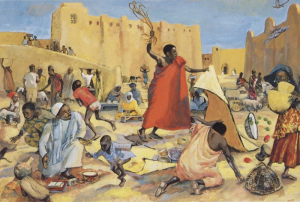

I’d like to move on now to our reading from the gospel of John. This is a passage which some people find very difficult to understand. Our image of Jesus as the gentle shepherd of his sheep is certainly put to the test in this passage as he storms into the temple and displays his anger. I don’t know about you, but I remember as a child, fighting or arguing with my brothers and stomping off, slamming doors and then facing the wrath of my mother. And so, I suppose, I should find this passage about the ‘cleansing of the temple’ quite reassuring. Here is Jesus, throwing things around in the ‘church’ of all places – the Jesus who was so calm and gentle the rest of the time. It makes me actually remember that he had human traits as well as being divine. John places this event early in Jesus’ ministry, instead of near its end, as the synoptic gospels do. There it becomes the act that helps to provoke his death. However, in John’s account, this movement to an earlier time in Jesus’ ministry means that the disciples are even more clueless than usual. They are new to Jesus, still trying to figure him out. They are still clinging to their ideas of who he is, rather than paying attention to what Jesus is saying about who he is.

Jesus Mafa Project Jesus Mafa Project

In this passage we see a new side to Jesus, someone who is so angered by what is going on in the temple grounds that he lashes out. It wasn’t so much that the temple authorities were selling animals for sacrifice, after all this is what people were coming to the temple to do, it was more that he could see that the authorities were being deceitful in what they were charging people. They were also rejecting some of the animals that people brought as having blemishes, so that people would have to buy from them. Another reason for Jesus’ anger was that people could only pay for the animals with temple coin. The money changers charged extortionate fees for exchanging Roman or Greek coins for temple coins, and of course the temple took its cut of the profits gained by the money changers. So it was not simply the presence of the money changers and the animals offered for sale that angered Jesus, after all, they were services meant for the convenience of people who had to travel long distances to get to Jerusalem. It was the misuse of authority in the blatant overcharging of even the poorest people that set Jesus off. People were stunned at the behaviour of Jesus, including the disciples who asked Jesus for an explanation. They couldn’t understand why Jesus said, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” It didn’t make sense to them, after all, the temple had been under re-construction for 46 years, how could Jesus raise it up in three days? As with so many things, the disciples only understood what Jesus had said later, in the light of the resurrection. We also know that the temple of which Jesus spoke was his body, not the bricks and mortar of the temple building! But there is another lesson to be learned from this reading, and that is the need for righteous anger, the righteous anger that Jesus displayed in the temple that day.

We need to have righteous anger in the face of injustice, extortion, and the exploitation of vulnerable people. Anger at such things is no bad thing, in fact it is a good cleansing thing. It is not the opposite of love. Anger at injustice is an appropriate expression of love and a cry for righteousness. Righteous anger is not a loss of control. Jesus is not out of control in this passage, he is very clear about the targets of his wrath. Righteous anger is about taking control, a move out of passive acceptance and towards change. Over the years we have seen change in the Scottish Episcopal Church. For decades now we have been working in our communities and beyond to bring change against racism, classism and poverty amongst others, and this can be seen in the Lenten appeals we support each year. We have also seen changes internally in the ordination of women and a fuller inclusion in the church of all people regardless of differing lifestyles, circumstances or backgrounds. And so, the challenge coming from our readings this morning, I think, is to remember that the wisdom and power of God is working in our lives, transforming us and moulding us into the people that God wants us to be. And as we are transformed, we should remember that we need that righteous anger to move us into action to help others however we can.

In your prayers this morning you may wish to pray for causes that are close to your heart:

• for people or countries facing injustice.

• for those who are struggling to feed their families.

• for those fleeing from oppression and abuse.

• and to ask God to grant you wisdom as you seek to follow in his way and to do his will.

Nerys writes: Have you ever ridden on the back of a bike that’s going too fast? That’s what it feels like to me sometimes when I read or listen to Mark’s Gospel. I want to shout, ‘Woah! Put the brakes on!’ In today’s Gospel passage, Mark 1.9-15, in just six sentences Mark has told the story of Jesus’ baptism in the river, his testing in the wilderness and the beginning of his ministry in the villages of Galilee. These important events whizz past and we’re on to the calling of the disciples and the stories of healing before we know it. So today, on the first Sunday of Lent, let’s put on the brakes and take some time to explore what Mark is telling us about Jesus and what we can learn from him.

So how does the passage begin? Here is the first sentence: In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan.

Mark doesn’t set the scene for us. Mark just gives us the bare facts. Let’s use our imagination to picture the crowds of excited people on the river bank. Can you see them flocking to John, that strange figure who had appeared in the wilderness? Can you hear his voice calling them to change their ways, to ask God to forgive all the things they’d done wrong, to come into the water to be baptised as a sign of a fresh start? Can you see Jesus queuing up with all these people? I wonder what moved him to respond to John’s call when he really didn’t need to be baptized at all?

Here’s the next sentence: And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him.

Mark zooms in of Jesus and what he sees as he is leaving the river. In Mark, these dramatic signs from God are just for him. The crowds are unaware of what’s happening to him. Their conversations carry on around him as the heavens are opened and he experiences an amazing vision of God who is about to do something new for the world.

This is something his people, the people of Israel, had been longing for down the generations. ‘O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the nations would tremble at your presence’ was the prayer of the prophet Isaiah (64.1). I wonder if this is when Jesus first catches a glimpse of God’s purpose for him. Is this the moment when he realises that he would be the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prayer?

Then out of heaven, God’s Spirit comes down like a gentle dove, not just upon him, but into him, filling him with power of God’s love. The same Spirit of God that moved over the face of the waters of the deep at the creation of the world. The same Spirit that would empower his followers at Pentecost and continues to empower us to this day.

Something else happens: And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.’

Later on in Mark, his disciples hear God speak these words about Jesus on the mountain top but just now they are for his ears only. I wonder how you imagine that voice saying those words? I wonder if you can imagine God whispering them to you right now? ‘You are my child. I love you and I delight in you.’

These words would have been familiar to Jesus. They are the words said by God in the Book of Isaiah about the Servant who is to suffer and die for the sins of the people (Isaiah 42.1-2): ‘Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations.’ I wonder if this is the moment when it becomes clear to Jesus that he is indeed God’s beloved Son, the healer humankind?

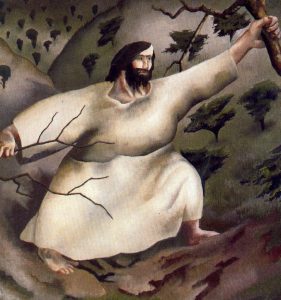

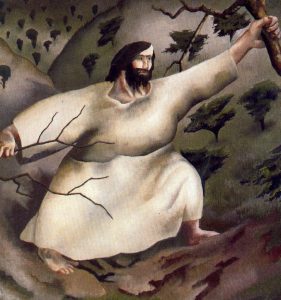

We’re left to guess what effect these words have of Jesus as Mark moves relentlessly on. And the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness.

Here Mark is at his most dramatic, using the most forceful of images. The Spirit immediately hurls Jesus into the wilderness. Ruach, the Hebrew word for God’s Spirit, can mean ‘breath’ but it can also mean ‘wind’ – a powerful, disruptive force.

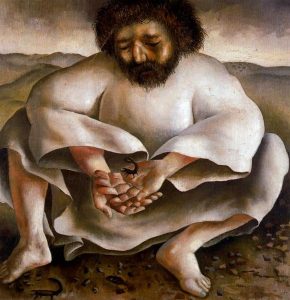

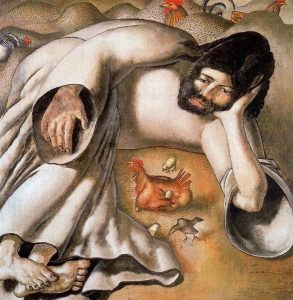

Stanley Spencer in the first of his famous series of paintings of Christ in the Wilderness, shows Jesus being propelled into the desert. See how he’s grabbing on to branches to steady himself as though he’s feeling a great force. Notice how his hair and cloak aren’t affected and the landscape remains still. This is an inner gale. This is God’s dynamic presence and power which continues to this day to push and pull, draw and drive God’s people here, there and everywhere, setting us on new pathways.

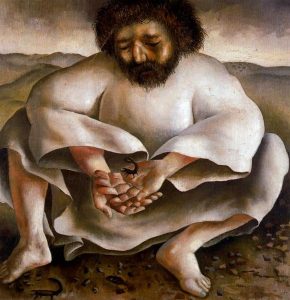

Mark has just one sentence on Jesus’ experience in the wilderness : He was in the wilderness for forty days, tempted by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angels waited on him.

Again, it is up to us to imagine the scene, to imagine those long days and nights in harsh, rocky surroundings as Jesus struggles with his thoughts and feelings. Mark doesn’t tell us the ways that Satan tests Jesus. We can only guess how the one who had opposed God’s people down the ages, seeks to deflect him from the path God has called him to. We aren’t given any details except that Jesus isn’t alone in the wilderness. Mark says that he is among the wild beasts and angels come to look after him.

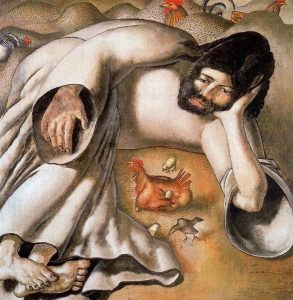

In the Judean desert. there would have been leopards, hyenas, vultures, venomous snakes and other dangerous creatures. Can you imagine sensing their presence in the darkness of night? Stanley Spencer depicts Jesus with all kinds of animals in his paintings. In one of them, we see him with a pair of scorpions, the most feared and deadly of the wild beasts of the desert. Instead of destroying them, Jesus cradles one in his hands and another one scuttles at his feet. I wonder how we respond to those things that strike fear in us?

God sends to Jesus angels to attend to his needs, just as God did to Elijah when he was at the end of his tether. They come to feed him, to encourage him, to comfort him, to bring him hope. Jesus is not expected to endure these trials on his own. God sends his servants to provide him with all he needs. I wonder if we have known angels in our lives who have supported and encouraged us in difficult times?

Mark, once more, says nothing about the effect these experiences had on Jesus. He simply tells us what happened next: Now after John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.

Jesus leaves the wilderness ready to begin his ministry. He is sure of who he is and what he is called by God to do. It is time for him to call others to turn to God and to trust in his message of God’s unconditional love.

I invite you to take a moment to bring to mind those times where you feel close to God, when you know that you are loved and blessed. Think of those times where there is testing and difficulty , when you feel threatened, anxious, afraid. Know that God is with you all the time and that God’s love is greater than any evil. Offer it all to God.

Join with me this week to pray for all people who are living in dangerous and difficult situations:

• for people in areas of the world where there is armed conflict,

• for those whose lives and livelihoods are affected by Climate Change,

• for refugees and asylum seekers around the world,

• for people who are in prison or homeless,

• for those in our community who are struggling financially,

• for those who are lonely,

• for those who are sick,

• for those grieving a loved one.

Loving God, during this Season of Lent show us by your Spirit how we can wait on those who need our support and prayers. Amen.

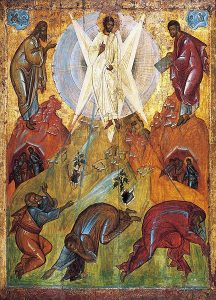

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, Peter writes, artists always paint the Transfiguration as their first icon. In fact, in the Orthodox Church they say the artist writes, not paints, the icon. That means it is created not just as a picture to be admired but to convey a message and to point to a meaning.

Icons and other religious art is not to be worshipped but to be honoured, venerated even, for the holy truth that it conveys. The Transfiguration scene calls out for visual presentation – with the three figures in a blaze of light on the mountain top and the disciples transfixed by the glory that shone around. At the centre is Jesus, his appearance transformed by this dazzling light. So what is this scene telling us?

15th century icon of the Transfiguration, unknown artist (public domain)

The light and the glory that shine forth are not reflected or have their source elsewhere. They come from within the person of Jesus himself. This is the uncreated light which signifies the divine nature of Jesus. But this divinity is present in a physical body, Jesus’ other nature, as a human being. It took the Early Church some 300 years to work this out and formulate it in the words of the Nicene Creed, which we repeat every Sunday: Jesus the Son of God and the second person of the Holy Trinity is two natures – human and divine – in one body.

Icons, and indeed most religious art, portray human bodies – of Jesus, his blessed Mother and indeed even God the Father himself. This is by no means idolatrous. We know perfectly well that God does not have hands but yet we happily sing “He’s got the whole world in his hands”. Like icons themselves, words like hands, eyes, arms are what our human language uses to help us get our heads round the reality that lies beneath and beyond.

The appearance of Jesus as a light-filled human body at the Transfiguration helps us to grasp the meaning of that phrase on the Book of Genesis, that God created us “in his image” and our bodies – and by extension our characteristics, personalities and capabilities all have the potential to illustrate or reveal the presence of God in our thoughts, actions and words. God has given us the gift of creativity, a sense of what is right or wrong, and a desire to work for the good of others. All this has huge implications for the way we treat our fellow humans, all of whom like us are made in his image. And, given that, to quote the First Letter of John “God is love and all who live in love live in God and God lives in them”, then it follows that the extent to which we love our fellow men and women, and indeed the whole of creation, must be the yardstick by which we measure the clarity, the brightness and the sharpness of the divine image in us.

As we come to God in prayer, in this coming season of Lent, examine ourselves and call to mind what we have done or failed to do, then we need to ask ourselves, “Have others seen God’s image in me? Do they see the light of his presence in my thoughts, words and deeds?”

And having examined ourselves, pray that we may embody that wonderful truth “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth”.

Rachael writes: Almost forty years ago now there was a disaster at sea. The doors of a ferryboat failed to close as it left the dock and water poured into its car decks. It listed to the side and panic began to set in amongst the passengers. The jovial atmosphere of a boat full of holidaymakers quickly turned into something more like a scene from a nightmare.

But in the midst of the chaos a man – an ordinary passenger on board – stepped up to take charge. With an authoritative tone he took command and gave instructions. People paid attention to him and, despite their underlying fear, were calmed enough to make their way to lifeboats that they otherwise would have missed in the crushing darkness.

The man himself made his way to the lower decks and to those trapped in the hold. The boat was now capsized, lying half submerged on a sandbank. People were trapped but the man created a human bridge with his body, creating a way across a damaged walkway by holding on to a ladder with one hand and another part of the ship with the other. Twenty people who would otherwise have drowned climbed across him to get to safety.

When the nightmare was over, the man was given a special honour for his bravery and selflessness.

Our story from Mark (1.21-28) takes place on a different coast, that of the Sea of Galilee (which is actually a lake), in the little village of Capernaum – population of maybe 1500 people in the first century. In the synagogue there, whose ruins you can still visit today, a man who nobody really knows and who certainly isn’t one of their usual preachers, begins to tell people what God’s will is, apparently all in his own authority. He didn’t caveat it with things like “as Moses said” or “as such-and-such said”, he just laid it out as he saw it with a quiet but compelling authority.

And in that same authority he speaks words of healing over those in need. Tom Wright describes those who came to Jesus as “people for whom life had become a total nightmare – whose personalities seemed taken over by alien powers”. The original audience of the gospel would never have questioned whether demons exist or whether healing was possible – the manipulation of the physical and spirit world isn’t the point that Mark is trying to make, nor is it Jesus’ aim either, because what his miracles symbolise is so much more important. Jesus has come to stop the nightmare: to rescue people (both nations and individuals) from the destructive forces that enslave them. And he’s going to do it by relationship and trust, not power grabbing or domination. He’s come to forgive sins and set people free from guilt, fear, and shame. God is changing everything, and changing forever the conditions in which human beings live. So whether its shrieking demons who accost him in the synagogue, a woman with a fever, or any other kind of disease that they bring to him, Jesus deals with them all with compassion and the same gentle but deeply effective authority.

It’s all part of how Mark shows us who Jesus is, especially in this very early depiction of his authority to set people free. It’s all part of Mark’s introduction to Jesus’ purpose and agenda. First, he shows Jesus to be the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy, then John the Baptist announces the coming of one who is stronger than him who will baptise with the Spirit, and straight away, in his baptism, Jesus is proclaimed as the Son of God. He’s then tempted by Satan before gathering together fishermen who immediately leave everything to follow him who knows where, because he just has that much authority! And then, as if we needed any more convincing, in the synagogue, at the heart of the provincial Jewish social order, in the very seat of the Establishment’s power, Jesus breaks down the boundaries and enters into a struggle against the forces of evil and destruction which, like the cruel sea pouring in on top of helpless passengers, seem to be engulfing all before them.

Mark is pointing, right here at the beginning with fifteen chapters to go, to the dramatic conclusion of Jesus’ ministry upon the cross. For it is on the cross, and not in power or miracles or scholarly debates, that Jesus calls out things for the way they really are and begins changing everything.

There, Jesus becomes the human bridge across which people climb to safety – with outstretched arms carrying people from death to life, from captivity to freedom. The man on the boat walked away with a medal but for Jesus the price of this saving authority, of this freedom for humanity, is his own life. The demons took their final shot at his authority as he hung on the cross but there he completed the healing, releasing work he began that day in the synagogue at Capernaum. There, as the sun grew dark and the temple curtain was torn in two, the centurion proclaimed “the Son of God!”.

We – created in the image of God, carried from death to life by Christ, and filled with the power of the Spirit – can be reluctant to walk in that same authority, despite the similar demons and nightmares that we find ourselves facing. The demons of illness, the nightmares of poverty, the horrors of hatred and war. The torments of greed and racism. They are similar, but not the same. Because, while they can still shriek, since Christ opened his arms to us all on the cross and burst forth from the tomb with arms still outstretched towards us, the demons no longer have authority in this world. We have been set free from their power and influence.

And that is what we share with our world: a steadfast resistance to the panic, fear and despair, saying “You have no authority here”.

Nerys writes: The repentant Jonah fresh from the belly of the whale, the psalmist beset by enemies, Paul, writing at a time of great pressure from imperial Rome, and Jesus, starting his ministry under the shadow of John’s arrest – in each of our readings today – Jonah 3.1-5, 10, Psalm 62.5-12, 1 Corinthians 7.29-31 and Mark 1.14-20 – we hear of a response to a call to God at a time of crisis.

It is often when we are in crisis that we turn to God, seeking God’s wisdom or guidance, comfort or strength. We trust that God will hear our calls of distress even when they come out of the blue, but will we recognise God’s voice when God responds to our plea? As the Vicar of Soham said in the wake of the murder of two schoolgirls in his parish many years ago now, when we’re drowning is not the best time to start learning to swim. Getting to know God’s voice takes practice. It is a lifetime’s work.

Our Gospel today is the first in a series of passages from the Gospel of Mark which will take us to the middle of Lent. I would like to encourage you to take time over the next few weeks to get to know God’s voice a little better by allowing God to speak to you through this Gospel.

Mark’s Gospel is a Gospel written at a time of crisis. Scholars think that it was produced either just after or just before AD 70, one of the most traumatic dates in the early history of the Jewish people. It was the year when Jerusalem was attacked and captured by the Roman army after a siege. Over a million people were killed and almost 100, 000 enslaved, the Temple was destroyed and the whole country laid waste. In its opening sentence, this work is described as an evangelion, a Greek word used for an important public announcement about a significant event which would change people’s lives for the better. It is a message of good news about someone called ‘Jesus Christ (Jesus the Messiah), the son of God’ . This was someone whose coming was prophesied by Isaiah and proclaimed by John the Baptist. This was someone who came to Galilee announcing a regime change. God’s kingdom is at hand. It is time to change the way we think and the way we live our lives.

The narrative forges ahead with breathless urgency and excitement. It is written in the style of the popular storyteller as a series of anecdotes vividly told, with short sentences strung together, the word ‘immediately’ appearing time and time again moving the action swiftly and jerkily along. This is not a Gospel to be read slowly, chewing on every morsel. In fact, it was probably intended to be listened to in single session.

When we read it like this, we can imagine the disconcerting and exhilarating impact this Gospel had on those who first heard it, and we can begin to understand what its author is seeking to do. For hundreds of years, Mark was felt by the Church to be inferior to the other three Gospels which are written in a more sophisticated style and present in more detail the teaching of Jesus. It was only in the nineteenth century that it was discovered that Mark wasn’t an abridged version of Matthew but the earliest surviving record of the life and teaching of Jesus. And it is only in the last hundred years that scholars have realised that it is not simple or naïve but ‘shot through with deeply theological perspectives’, to use the words of Rowan Williams.

It is when we read or listen to it from beginning to end that we notice, that although Mark is the shortest of the four Gospels it consistently provides much more detailed descriptions of events than Matthew and Luke. In the account of the feeding of the five thousand, for example, Mark tells us that the grass the people were sitting on was green. This little detail which indicates what time of year the miracle happened, not only makes the story more vivid but also according to some scholars, suggests that it is based on an eyewitness account of the event. The identity of Mark has been lost in the mists of time, but there is an ancient tradition that he was the secretary of St Peter. This was recorded early in the second century by a bishop who had learnt it from his churches in Asia Minor. According to this tradition, Mark not only wrote down but also interpreted what Peter had said to him, so that it would be accessible to new hearers and readers.

It is when we read the Gospel from beginning to end that we begin to see the great skill and artistry behind the presentation of this series of apparently simple stories. Threads of continuity come to light and we notice repeated behaviour in the three groups of characters who appear regularly in the story. The religious authorities – priests, scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees – are suspicious, sceptical and argumentative opposed to Jesus from the start. The crowd which appears more consistently in Mark than in the other Gospels, is impressed by his teaching and his miracles but its members never seem able to take a step beyond expressing wonder and amazement. The disciples follow Jesus but never really grasp who he is and what he had come to do. It is only the ragbag collection of people in crisis – like the man possessed by demons, the woman who is haemorrhaging blood, Jairus whose daughter had died, the Syrophoenician woman or the blind man from Bethsaida – who recognise him as the Christ, the Son of God, and call out to him for help. The way Mark portrays these characters doesn’t just draw us into the story but challenges us to respond ourselves to Jesus from amidst the crises of our lives and our times.

I urge you to sign up to meet with others in the congregation to hear Mark’s message of good news read in a single session, or failing that, to set aside an hour and a half sometime in the next few weeks to read it through yourself. Allow this ancient little book to work on you, to bring you closer to Jesus so that you will better recognise God’s voice.

An icon of St Mark written by Diana, late wife of Hugh Grant.

Nerys writes: A few weeks ago, Peter was telling us that Advent was his favourite season in the church year. I think that I prefer this season of Epiphany which starts on such a dramatic note with the revelation of Christ to the wise men and contains such a rich and varied selection of readings, culminating in the mountain-top revelation of Christ to his disciples on the last Sunday before Lent.

This week’s passages present us with a tapestry of images of the One who seeks us out, draws close to us, inhabits us and calls us to service.

In our Old Testament passage, 1 Samuel 3.1-10, we read of the boy Samuel ministering to God even though he did not yet know God. ‘Go, lie down’, Eli says to him, ‘and if he calls you, you shall say, “Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening.”’

‘O Lord, you have searched me and known me’, the poet prays in Psalm 139. ‘You know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from afar. Even before a word is on my tongue, O Lord, you know it completely.’

‘Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ?’ Paul asks in 1 Corinthians 6.12-20. ‘Do you not know … that anyone united to the Lord becomes one spirit with him?’

“How did you come to know me?” Nathanael asks Jesus in our Gospel, John 1.43-51.

Again and again the word know appears, reminding us of God’s desire to know us, and for us to know God. At the beginning of this season of Epiphany, a season whose focus is on the revelations of God in Scripture, I think it is worth taking some time to ask what do we mean and how do we feel, when we talk of God knowing us and of us knowing God.

In English, ‘to know’ has a very wide range of meanings that require two or more verbs in other languages. In my native Welsh we have gwybod and adnabod, in French we have connaitre and savoir, in German we have wissen, kennen and erkennen. Some of you will know of other languages, like Spanish and Italian where a similar distinction is made between knowing a person or a thing and knowing a fact.

Our psalm for today is a celebration of all aspects of God’s knowledge of us. It tells us in detail how we are known completely by God. Wherever the psalmist goes, whatever he says and thinks, all is known to God. No detail in his everyday life is too small for God not to know about. This is a wonderful mystery according to the psalmist, but I wonder how thinking about it makes you feel?

In our age of widespread surveillance, the idea that we can’t escape from God’s knowledge of us may feel threatening. But if we are anxious or even frightened by the thought of an all-knowing God, we are missing the point of the psalm. The Hebrew word for ‘know’ has an even wider range of meanings than the English and includes the sense of having an intimate relationship with someone. To be known by God is to be loved by God. When we get to know God, we learn that God is not an intruder invading our privacy by stealth or by force. Neither is God’s persistent presence with us designed to keep track of everything we do wrong. God’s deepest desire is not to control us, but to invite us to know the unlimited and unconditional love that God is.

Rather than being a threat, being known by God is a great comfort to the psalmist. When we have an awareness of the presence of God who has known us from the moment of our conception, who is familiar with every aspect of our lives, who understands us better than we understand ourselves, we never need to feel alone. There can be times when we’re suffering the loss of a loved one or experiencing pain or battling illness when we feel that no one fully understand what we are going through. With God there are no moments, however dark, which we need to face alone. There is nothing, no hurt or trauma, no disappointment or shame, in our lives that God isn’t concerned about. God knows the story of our lives. God is aware of the sources of our fear or anger or guilt and understands what they are doing to us and what they are doing to others.

When we allow God to be intimately involved in our lives, accepting as Paul does, that our bodies are not our own but are temples of God’s Spirit, members of Christ’s body, God can use this knowledge of us to protect us and care for us. This is the psalmist’s experience. ‘ You have hedged (or enclosed) me’ he says – the Hebrew verb deriving from a word often used of a military fortification. ‘You have laid your hand upon me’. Knowing that God’s love is working for good in our lives frees us to work for the good of others.

I find it reassuring that God knows all about us and understands us before he calls us. When I look back at my life, I remember a time when, like Samuel, I didn’t know God but I can see now that God already knew me well and that God used that knowledge of me and those around me in order to draw me close enough to hear God’s voice. We are told that Samuel did not yet know God but through his mother’s prayers he had been placed in God’s house under the tutelage of someone who could guide him and teach him God’s ways, and on that fateful night helped him to recognise that it was God who was calling him.

We don’t know what Nathaniel was doing underneath the fig tree. Some scholars claim that he was studying the Torah, others that he was keeping alive an ancient dream of his people. The Chosen, a dramatization of Jesus’ life that some of us have been watching, has him sheltering there at a time of crisis in his life. Whatever it was that he was doing, Nathaniel, like the young Samuel, had made himself available to the God he did not yet know. A word of encouragement from Philip leads him to Jesus who only needs to refer to that moment under the tree for Nathaniel to know that he was known and to express his faith in the most unlikely of Messiahs. This was my experience too. After many years of making myself available to the God I didn’t yet know, I was invited by a friend to ‘come and see’. At that meeting, it was revealed to me that I was loved by God who knows me through and through. Something changed in me. I no longer merely knew about God but knew God through Jesus. I experienced his forgiving and healing love, and from that point my faith began to grow.

We are not told what happened to Nathaniel after that day but Jesus’ promise that he would ‘see greater things’ suggests that he would become a follower, witnessing the miraculous healings and signs recounted in the Gospel. For Samuel, God’s call to service followed swiftly on from his recognition of God’s voice. In a world that largely doesn’t yet know God, we who do know and love God have work to do. We are called to introduce others to Jesus like Philip did and to guide and support them as Eli did. I wonder how will we respond this week and through the course of this new year, to that call?

Mark Cazalet, ‘Nathaniel under the fig tree’ (Methodist Modern Art Collection)

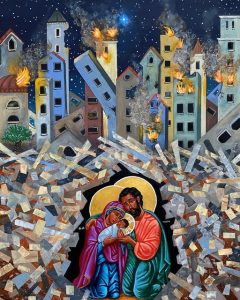

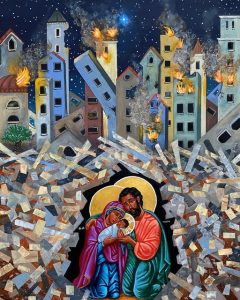

Nerys writes: Yesterday morning, I tried very hard to prepare a sermon for our Midnight Eucharist but the words just wouldn’t come as they usually do. After several hours of grappling in vain with my thoughts, I heard two pings from my mobile phone. Two friends had sent me messages at the same time, one containing a poem, the other an image, both created in response to the horrors of the last few months. This confirmed to me what I already knew deep in my heart, that for me, this Christmas is not a time for talking but for holy silence as we come together to mark once more the coming of Christ, born into the rubble of the world which we have broken.

I invite you to join me in putting aside some time to read Thom Shuman’s poem and explore Kelly Latimer’s icon, using them as way into prayer this Christmas.

Kelly Latimer, Christ in the rubble

the creche is empty this year . . .

Mary is sitting with the mothers

whose children have been buried

under the rubble, weeping and wailing

together, arms wrapped around one

another in chronic grief

Joseph has put his tool belt

around his waist, slowly and tenderly

building as many coffins as he can

with the splintered pieces of

destroyed homes and buildings

the shepherds are sitting

the long line of aid trucks

just waiting for the signal

that they can begin driving

their trucks loaded with food,

medicine, fuel, and water for

the people in desperate need

the animals are tagging along

as best they can, trying to keep

up with the long line of families

who once more are turned into

displaced refugees from their land

and the angels have fallen silent,

cupping their hands to catch

the falling tears of the One

who sees beloved children

dying needlessly, while forgotten

(c) 2023 Thom M. Shuman

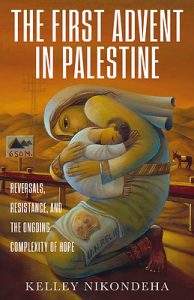

Nerys writes: During the last few weeks, I’ve been reading a book which I’m finding is sustaining me during what has turned out to be a difficult Advent in many ways. I don’t know about you, but for me it’s going to be hard to find much joy in our Christmas festivities this year. It doesn’t feel right to be carrying on as usual when there is such killing of innocent people happening in places like Gaza and in eastern Ukraine, when so many people have been driven from their homes by war and climate disasters and when there is so much economic need in our own communities. What I have learnt from this book, and what gives me hope in the face of the horror and terrible injustice of today, is that it was in a very similar circumstances that Christ was born.

Over the years we have sanitized and prettyfied the Gospels’ account of the first Christmas until it bears little relation to its historical setting in first century Palestine and has little to offer anyone living in troubled times like ours. The book I’ve been reading sets the story in the political and economic landscape of the time – a time of darkness and danger for the Jewish people. For generations they had suffered at the hands of one empire or another and now they were under Roman rule. Caesar had announced the Pax Romana and had been declared the saviour of the world. Through crushing military victory and control maintained through violence, the Romans had ended the cycles of endless wars and brought about world peace. It was at this time that God who is love, came to the hills of Judea and to a village in Galilee to begin a different kind of peace campaign.

God first came to Zechariah, an ordinary priest, and his elderly, childless wife Elizabeth. God then reached towards Galilee to find someone to collaborate with in a plan for a kind of peace that didn’t rely on violence or war or on turning people out of their homes. While the Roman empire would soon collapse, God’s peace would be good news for oppressed people the world over for ever.

But the coming of the Messiah was nothing like any good first-century Jewish man or woman expected. No one anticipated the place or the person that God would approach – least of all Mary, the girl from Galilee.

The people of the north were considered inferior by those in Judea and Jerusalem. Over the centuries they had intermarried with other peoples, they didn’t observe the Jewish Law to the same extent as their southern neighbours and didn’t worship regularly in the temple. These villages were places of resistance to foreign rule – the people always waiting for the next act of aggression in a cycle of protests, uprisings and reprisals. This was the last place anyone expected to be on God’s map.

But it was to Nazareth in Galilee that God sent the angel Gabriel, to the last person you would expect – a local girl from an ordinary family. The Mary of our Christmas cards dressed in blue with her delicate beauty, calm and serene, is not the Mary of Luke’s Gospel. This girl on the verge of becoming a woman would have been shaped by trauma – the collective trauma of her people, humiliated and oppressed for centuries on end, and perhaps personal trauma, existing as she did in a precarious place where sexual violence against women and children was widespread. But a young woman like her, living at a time of great political tension which often spilled into violence, would also have been formed by resistance.

The author of the book I’ve been reading, likens Mary to members of the current generation of Palestinian women in the West Bank who refuse to accept the Israeli occupation. Women like Abed Al Tamimi, from the small village of Nabi Saleh, not unlike Nazareth, who at the age of 16 was arrested for slapping an Israeli soldier. She had grown up marching in community protests against the Israeli settlers who had taken over the village spring and much of their agricultural land. She was only ten when Mustafa, her cousin, was killed by soldiers. The following year, she witnessed the arrest of her mother (which she herself tried to stop) and then the arrest of her older brother. When soldiers came to her front yard just weeks after shooting another of her cousins in the face, she reacted with her fists. The next time the soldiers came, it was to take her to prison.

Before she became and adult, Abed Tamimi had developed a spine of steel. At the age of 22, she continues to resist the occupation, regularly risking her freedom and her life in her community’s quest for justice. Two thousand years earlier, Mary would have seen soldiers riding into Nazareth, terrorizing her neighbours in the name of peacekeeping. She would have witnessed uncles humiliated, cousins hurt and female relatives taken by force to be punished in unspeakable ways. While the men in her community took up arms to protect their lives and land, she might have composed songs of grand reversals and unlikely victories. Formed by trauma and resistance, she would have understood justice as rebellion against the oppression of the empire.

But before she herself could push against it with violence, Mary was pulled into God’s peace-making initiative. The angel insists that she has found favour with God. God’s Spirit would overshadow her body, and she would conceive the Son of God, a rival to Caesar, one who would be able to reshape the world according to justice, bringing a different kind of peace. Mary listens to the promise of the healing of so much hurt and responds with confidence borne of trust. The young rebel is ready to be at God’s service.

In the courtyard of the Church of the Annunciation built on the foundations of what is thought to have been Mary’s home in Nazareth, there is a collection of images from across the world. Most are the classic Madonna and Child motif but each reflects the nation of the artwork’s origin. Together they represent the ways in which Mary and her son continue to be embodied in those precarious places in the world where mothers are practicing non-violent resistance to oppression and teaching their children to hunger for justice and peace

May we in our prayers and actions support those who are continuing what Mary started with her ‘Yes’ to God, and in our own lives may we hold on to the hope which the coming of her son offers us in these dark days.

Kelly Latimore icon: Mother of God: Protectress of the Oppressed

ALMIGHTY God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light, now in the time of this mortal life, in which thy Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility; that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious Majesty, to judge both the quick and the dead, we may rise to the life immortal; through him who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, now and ever. Amen. (The Scottish Prayer Book)

Peter writes: This ancient prayer, the Collect for the first Sunday in Advent, is one of the great treasures of the Church. Read it out loud to yourself and listen to the way the language flows. Then notice the series of contrasts: “the works of darkness – the armour of light; now, in the time of this mortal life, in which thy Son came to visit us in great humility – in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious Majesty; the quick and the dead.”

The word visit has changed its meaning. Here it does not mean dropping in for a cup of tea but to inspect, to inquire about. Advent is a time to cast light in the dark corners of our mind, our conscience and to reflect on the fact that the world is a dark place. We are reminded that we shall be called to account. But we can have confidence that the judge is merciful and that we shall rise to life immortal. All the great themes of Advent are gathered (“collected”) in this wonderful prayer.

I am also a great fan of our 1982 Liturgy, especially the Eucharistic Prayer for Advent. In fact, In fact I spent the past two Advent seasons in churches where they use the English liturgy but I smuggled in (shh!) the Scottish prayer. Just as the collect looks back to Jesus’ presence with us in great humility as well as forward to the time when he shall come again in his glorious majesty, so, with its references to a creation, a kingdom given, yet still to come, the prayer speaks of past and future collapsed into a single present, into God’s timelessness. Indeed every time we celebrate the Eucharist our divisions of time into past, present and future are similarly transcended: we present our offering now and we look forward to the healing of a broken creation at the end of time, manifested to us in the present by the transformation of bread broken and wine poured out.

A third reason for loving the Advent season is the music. At this time of the year we sing some of the best hymns in the book, for instance Charles Wesley’s great Lo, he comes with clouds descending and the mediaeval O come, o come Emmanuel, with its haunting melody that speaks of waiting and longing together with a note of triumphant expectation. A more recent hymn is People, look East whose rather jaunty melody captures the atmosphere of growing excitement and the words remind us that Advent is a time of preparation: “Make your house [your mind, your soul] fair as you are able”. Best of all, although it is probably better suited to a choir than for congregational singing, is Bach’s great cantata Wachet auf! (Wake, o wake!). Here, “wake” refers to the need to be alert to the sign’s of Jesus’ presence in our daily lives as well as to the life to come at the end of time. As if that were not enough, since reading through today’s first lesson, O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion and other pieces of Handel’s Messiah have been going through my head.

No wonder, then, Advent is my favourite among the Church’s seasons. It is just a pity that it is so short and gets drowned out by carols. Enjoy the feast of Advent while you can!

For prayer and reflection

Read through the Advent collect and the Eucharistic Prayer II. (You will find it on the SEC website; follow the links Who we are: Publications: Liturgies: 1982 Scottish Liturgy).

Read them slowly and meditatively.

Ask yourself:

– where are there works of darkness in my life, in the world today? Pray for help, protection and guidance.

– where do you see signs of Christ’s transforming presence in my life or in the world in the form of words and deeds? Give thanks for them, pray for the people and organisations involved.

– in spite of, or perhaps because of, all that is going on, what does it mean to look forward with hope?

Nerys writes:

It seems to me that Christmas is starting earlier every year. Today is Advent Sunday and I’ve already led a Christmas carol service, visited a Christmas craft fair and the Extravaganza, sung carols around a Christmas tree and eaten three mince pies! Perhaps 2023 with its brutal wars, the suffering caused by the effects of Climate Change and the economic after-effects of the pandemic has caused many of us to crave some semblance of joy. It is natural to want to turn our backs for a few weeks on all the devastation and desperation and focus instead on things that make us glad.

Carols at Cromlix

I find it fascinating, however, that in the calendar of the Church, before any moment of celebration there is a season of lament and penance. Advent precedes Christmas and Lent precedes Easter. Our church fathers and mothers understood that a night of doubt and weeping comes before a morning of true joy. This movement from darkness to light is at the very heart of our worship.

In today’s Old Testament reading, Isaiah 64.1-9, the prophet takes us from lament to hope on an emotional prayer journey. His oracle starts with complaint and protest. He appeals directly to God to ‘rend the heavens and come down’. He lays bare the truth of his own experience and that of his people, a nation devastated by years of oppression and exile, and in doing so he expresses his trust that God will hear his desperate call. The honesty of his prayer makes him vulnerable and open to inner change. Lament helps us to move forward with God to a place of hope.

The prophet recalls past times when God acted powerfully on behalf of his people: ‘when you did awesome deeds that we did not expect.’ In difficult times, I find it helpful to look back at my life and to remember how good God has been to me. I bring to mind the special people God has placed in my life, the doors God has opened for me, the unexpected strength and comfort God has given me. In his prayer, Isaiah not only reminds himself that he and his people have history with God but also reminds God that he has a history with us. On that basis, he appeals to God to provide for his people again. Moving from lament to hope requires conversations about the past.

It also requires deep reflection on our present relationship with God. Isaiah speaks of the way his people have fallen short in their commitment to ‘the one who works for those who wait for him’. It makes them feel unclean and worthless, he says, like a dirty rag or a leaf blown by the wind. Many of us carry a lot of baggage in our hearts which is not only weighing us down emotionally, but is distancing us from God. I find that it is good to share with God the things that are bothering me. We can trust God with the deepest and darkest secrets of our lives because we know that God cares for us and will not hurt us.

As it nears its conclusion, Isaiah’s prayer shifts from confession to an expression of trust in God. The prophet proclaims, ‘Yet you, Lord, are our father’, and calls on God to come and see about his children. St. Paul expresses the same deep trust in God’s faithfulness in today’s New Testament passage, 1 Corinthians 1.3-9, as he prays with confidence on behalf of the young Christian community in Corinth. Hope comes from our assurance that God is faithfully watching over us, ready to respond to the deep desires of our hearts.

In today’s Gospel passage, Mark 13.24-37, Mark’s Jesus presents us with three stories to remind us that, however bleak things get, he has not forgotten us and will never abandon us. He is always with us and will come again to put things right in our world. In the meantime, we wait trustingly, mindfully, hopefully and actively.

I wonder what form your Advent waiting will take this year? You may wish to use as a starting point for your reflection this Advent prayer written by Val King, Head of Christian Aid in Scotland.

Waiting is hard Lord.

We wait to hear news of peace with justice,

we wait to greet the day when all will have enough,

but we don’t wait passively.

As we wait again for your coming,

strengthen us in our resolve to work to make your kingdom come on earth.

Amen.

Rachael writes: I heard a story this week about a church youth group. On this particular evening their leaders had planned a hunger feast for them. It’s an object lesson in fairness and equality, and really in economics. The young people were to be divided into four groups. The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on. The biggest group would sit on the floor around one bowl of rice. The next group, slightly smaller, would sit around a bowl of rice and beans. The third group, much smaller again, were each given their own bowls of rice and beans. And then one person would be given a seat of honour and large platter of meats, cheeses, fresh bread, little nibbles – like a sharing board at a fancy café. The young people were randomly assigned to each group by pulling names out of a hat and the girl given the place of honour was the girl that everyone picked on.

No matter how hard the leaders had tried to squash such behaviour, she was left out on purpose and made fun of for what she wore and how she talked. When she pulled out the card for this fabulous tray of food, the rest of the group were annoyed and grumbly. A couple of girls even pulled a leader aside and said “It’s not fair that she gets everything, she’s so weird”. Some were even heard to say that she didn’t deserve it but that it should surely go to the cool people. While the adults in the room whispered to each other that justice had finally been served.

But the girl, sitting by herself with this beautiful spread in front of her, had tears streaming down her face. “It’s not fair,” she said. “I don’t like it. It’s not fair that no one else gets this and they should”. The leader asked her what she would like to do and after thinking for a few minutes she got up from the table with her platter and began to go around the groups making each person a sandwich from her board of goodies. There was an awkward and uneasy silence as people began to eat. Finally one person asked the girl “Why did you do that? We’re kind of mean to you all the time. If I were you, I would have eaten it all myself”.

And in the most eloquent moment, the girl stood before them and said, “You’re right. You’re not very nice to me and sometimes that really hurts. But Jesus reminds me that we love each other all the time. It doesn’t help me to keep this for myself but I want you to be a part of this party with me. The pastor tells us that everyone is invited to communion and think this is the same thing. I know what it’s like to not be invited and don’t want anyone else to feel the same way. So, sandwiches for everyone! Because God loves me, and you.”

Out of the mouths of babes…

This young girl understands the heart of the Kingdom of God. She knows what it means to live under the reign of Christ, and to participate in the world with Christ as your King.

We adults can become so jaded. I remember being 17, 18, 19, and thinking that I was going to change the world. But we get worn down by the heaviness of responsibility, by the need to just get through the day, by the constant stories of injustice and inequality, so that we start to think that change will never happen. That there will always be those who share the bowl of rice at one end and those sitting with the platters of luxury at the other – and nothing will change that. This girl, however, first of all uses her own experience to shape her response and to lead her to compassion. It could, as one of the others said, have taken her to bitterness and selfishness but instead she is moved to empathy. Then she turns that heartbreak into action – radical, selfless, courageous, and risk-taking action.

Which is exactly what our passages today point us towards. It’s interesting to me that on Christ the King Sunday we’re not given a vision of Christ in glory reigning over us but of an upside-down, inside-out, transformative Kingdom. We are given somewhere to believe in.

I wonder if you’ve ever been to a place and thought “this must be what heaven is like”. Maybe it was sunshine and white sandy beaches. It might have been a particularly excellent meal. I can think of a few myself – one being a vista at the top of an Italian mountain that brought me to actual tears; another being the festival that we go to in the summer, Greenbelt.

There, sharing communion with 9,000 people from all walks of life and all kinds of church backgrounds, with the elderly and tiny babies, with goths and bishops, with people in wheelchairs and people bedecked in rainbows and glitter, I feel like I get a tiny glimpse of what heaven, of what the Kingdom, might be like. The festival’s tag line is “Somewhere to believe in” (I even have it on a t-shirt). And I think that we all need to know where we’re going, what we’re aiming for, and as good as Greenbelt might be, as beautiful as those mountains and beaches were, or delicious as that meal was, the descriptions in Ezekiel and Matthew are better. They tell us of a place where freaks are ushered in, the famished are lavished upon, the vulnerable and shamed are wrapped up in love, and the light goes to dwell with those in darkness.

I remember, as if it were yesterday, the first time I read this passage when I was fifteen. It transformed my understanding of what it means to follow Christ and it continues to challenge me that walking with Jesus isn’t about “nice” or “comfortable” or “gentle”, but about radical, counter-cultural, and courageous love. Love that is risky. Love that is action. Love that is faith, in word and deed.

Let me encourage you, fellow sheep of the fold, to keep going. To continue to see Christ in everyone you meet. To open your hearts, your homes, our church, to those on the margins and in need. To keep your compassion and your courage. Have in mind the somewhere we believe in and, by God’s grace, may we see glimpses of it in the here and now. Amen.

Nerys writes: I don’t know how many of you, like me, are looking forward to the final of the Great British Bake Off at the end of the month. I have been a fan of the programme for many years now. I am fascinated by the creativity which the challenges bring forth in the contestants and enjoy the suspense surrounding the adjudicating as, week by week, one baker after another is sent out of the tent. I read somewhere that a formula has been worked out to predict which of the competitors are most likely to win, based on their gender, age and where they come from, but I’ve noticed that it is often another more important factor that ensures success in this and other similar programmes. It’s the same quality that Jesus encourages in today’s Gospel, Matthew 25. 14-30.

The Parable of the Talents is often interpreted as a tale with a moral about investing our natural abilities, our skills, our resources in the service of God. But the more time I’ve spent reflecting on Matthew’s version of this story, the more I think it may be about something else. This is the second of two parables where Jesus says that he is giving his listeners a picture of what the kingdom of heaven will be like. The first story is about the relationship between ten bridesmaids and the bridegroom they are waiting for. This one is about the relationship between three slaves and their maverick master.

The Three Servants by Nelly Bube

The first two slaves who successfully invest their master’s money and are rewarded on his return, seem to act as a foil against which to compare the third who is a much more rounded character. It is his interaction with his master and his punishment which forms the climax of the story. We get to see the master through his eyes as a harsh man who takes what is not his and strikes fear in the hearts of those around him. In return, the master calls him wicked, lazy and worthless. But we get a more accurate picture of both characters if we focus on their actions rather than on their accusations of each other.

Far from being harsh and exploitative, the master acts in an extremely generous way, entrusting each of his slaves with a huge amount of money. (In the first century, a ‘talent’ would have been worth half a lifetime’s earnings for a day labourer.) Moreover, the master seems to know each his slaves well. He treats them with care and discretion, taking into account their capabilities so as not to impose an unreasonable burden on them. He doesn’t issue specific instructions for them to follow but gives them the freedom and the power to use their initiative. Then he goes away, giving them space so that they can act

independently of him. And far from reaping what he didn’t sow, he not only returns to the first two slaves the enormous wealth they had accumulated but also invites them to share with him his joy, transforming their relationship into one of friendship.

These slaves respond to his trust and his risky generosity by rising to the challenge unlike their colleague who returns exactly what was given to him, having buried his treasure in the ground. Despite his master’s characterisation of him, his actions show that the third slave isn’t a bad man. He doesn’t squander the money he was given or use it for his own benefit. In fact, in the first century what he does with it would be regarded as much more responsible than the risky speculating of the other two. He admits, though, that his actions are driven by his low regard of his master and it is this, I think, that leads to his downfall.

Time and time again in TV contests I’ve seen competitors being sent home for playing it safe rather than take a creative risk. Instead of regarding the judges as allies who wish to give them opportunities to shine, their fear of their criticism causes them to take a less challenging route. It appears that in the Kingdom of God as in the Bake Off tent, the greatest risk of all is not to risk anything. Paralyzed by his fear and distrust, the third servant rejects the opportunity the master graciously gives him to imitate his risky and trusting approach to life. Jesus’ warning is that the outcome of playing it safe, of not being ready to invest yourself or risk anything in response to God’s astounding generosity is like being banished to the outer darkness.

All our readings today remind us that what we think of God and how we respond to God’s call on our lives is important. We have real choices and power but there are consequences resulting from the ways we use our freedom. What we do or fail to do shapes our lives and our world.

Zephaniah’s prophecy in Zephaniah 1.7, 12-18, contains a relentless attack on those among the Israelites of his day who had a complacent attitude towards God – those who thought they could put God in a box and focus on living a materially comfortable life. They will know the consequences of their neglect of the poor, writes the prophet. To them, God will come as a hostile and destructive army, taking away all their security and giving them only terror.

Paul in 1 Thessalonians 5.1-11, has a similar message for those Christians in Thessalonica who were tempted to put their trust in living a quiet life under Roman rule. It was as if they were being lulled to sleep by the Empire’s comforting slogans of peace and security instead of living their lives fully and faithfully in the light of the Gospel.